Stanford, CA—How much of the ability of a coral reef to withstand stressful conditions is influenced by the type of algae that the corals hosts?

Corals are marine invertebrates from the phylum called cnidarians that build large exoskeletons from which colorful reefs are constructed. But this reef-building is only possible because of a mutually beneficial relationship between the coral and various species of single-celled algae called dinoflagellates that live inside the cells of coral polyps.

The algae are photosynthetic—meaning capable of converting the Sun’s energy into chemical energy for food, just like plants. And the exchange of nutrients between the coral and the algae is essential for healthy reef communities. The coral provides the algae with carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and other compounds that they need to survive and perform photosynthesis. The algae, in turn, can stimulate the growth of the coral by providing them with sugars and fats, which are created via photosynthesis.

An international research team based in New Zealand and including Carnegie’s Arthur Grossman set out to determine how the abundance and diversity of sugars and other carbon compounds shared with the coral varies between species of algae and what this could mean for a coral’s ability to survive under stressful conditions caused by climate change. They did this by studying the anemone Aiptasia—a cnidarian like the coral—which can also host symbiotic dinoflagellates, but it grows much faster and is easier to study than corals.

Their findings are published by Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

“We’re very interested in what happens when external conditions force corals to switch from hosting one symbiotic algal species to another,” Grossman said. “Having a long-term symbiotic relationship with a native algal species is advantageous to the coral. But if the surrounding conditions are altered by climate change, could a different algal species confer corals with improved fitness and chances of survival?”

When comparing the sugars, fatty acids, and other metabolic products transferred to the host anemone by two different species of algae—one native, the other a transplant that’s not normally found in the anemone host—the team found that the native species consistently provided more nutrition to the anemone than the non-native one.

However, the transplanted “poor provider” algae used in this research, called Durusdinium trenchii, is known to have a high heat resistance and it’s been observed to repopulate coral communities that have been damaged by bleaching and have lost their original algal tenants.

“Under normal conditions, coral or anemones that host a species of algae that’s a poor nutrient provider will be forced to burn its own energy stores and take in nutrition from the surrounding water,” Grossman explained. “But in the wake of a bleaching event, even a poor provider may be better than no provider.”

Further research that involves a greater variety of algae and studies the flow of nutrients between the organisms in greater detail is necessary to fully understand if more heat tolerant but less generous algal species might help these fragile ecosystems survive a world in which the climate is rapidly changing.

Other members of the research team were: lead author Jennifer Matthews and colleagues Clinton Oakley, Katie Hillyer, and Simon Davy of Victoria University of Wellington; as well as Adrian Lutz and Ute Roessner of The University of Melbourne Parkville; and Virginia Weis of Oregon State University.

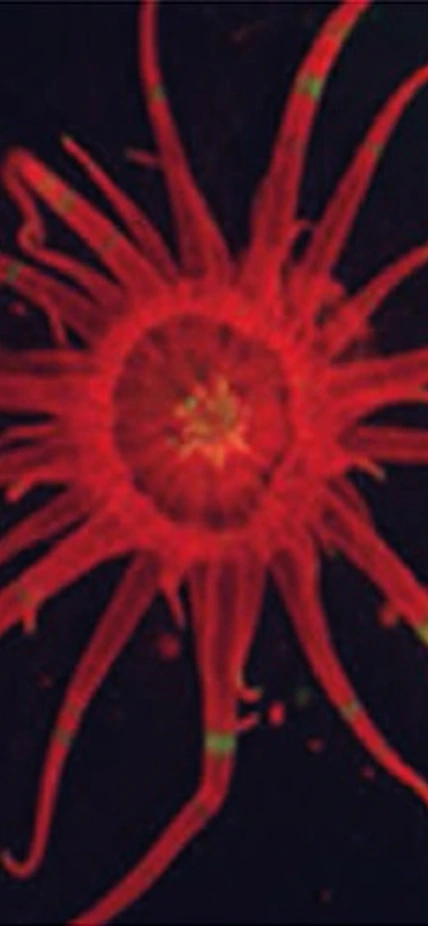

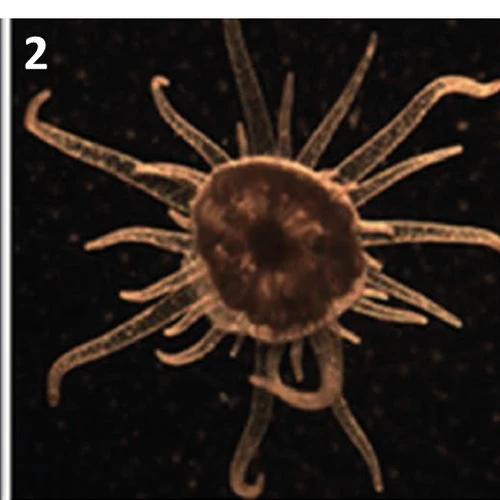

Caption: Panel 1 shows a bright field image of the anemone, Aiptasia pallida, the model cnidarian used for the team’s studies, which is lacking endosymbiotic algae. Panel 2 shows a bright field image of the Aiptasia populated with its symbiotic algae. Panel 3 shows a fluorescence image of the populated Aptasia. The red fluorescence is from the algae’s chlorophyll.

_______________

This work was supported by the Company of Biologists Journal of Experimental Biology Travelling Fellowship and a grant from the Royal Society Te Apārangi Marsden Fund.