Graced with clear, dark skies and an exceedingly arid climate, Chile's Atacama Desert boasts astronomical "seeing" that is the best in the world. It has become a mecca for stargazers with more than 20 observatories dotting its austere landscape. Over 50 years ago, Carnegie astronomers chose to build an observatory in the Atacama—the institution's Las Campanas Observatory—which would become the cornerstone of Carnegie Science's modern astronomical research program.

A Century-Old Vision

The idea for Carnegie Science to build a southern observatory is almost as old as the institution itself. In 1902, the Advisory Committee on Astronomy set forth a bold argument for a southern viewing station. Their report, published in the institution’s first year book, noted that Northern Hemisphere observatories outnumbered southern facilities by 10 to one, creating what they termed a "great deficiency" that "ought to be remedied." The skies of the Southern Hemisphere, home to the Galactic Center, the Magellanic Clouds, and countless celestial objects invisible from northern latitudes, were astronomically neglected. The committee's remarkably foresighted recommendation for a southern hemisphere observatory acknowledged that such an ambitious project "may not be realized in full for many years to come." In fact, it would take more than six decades to fulfill their vision.

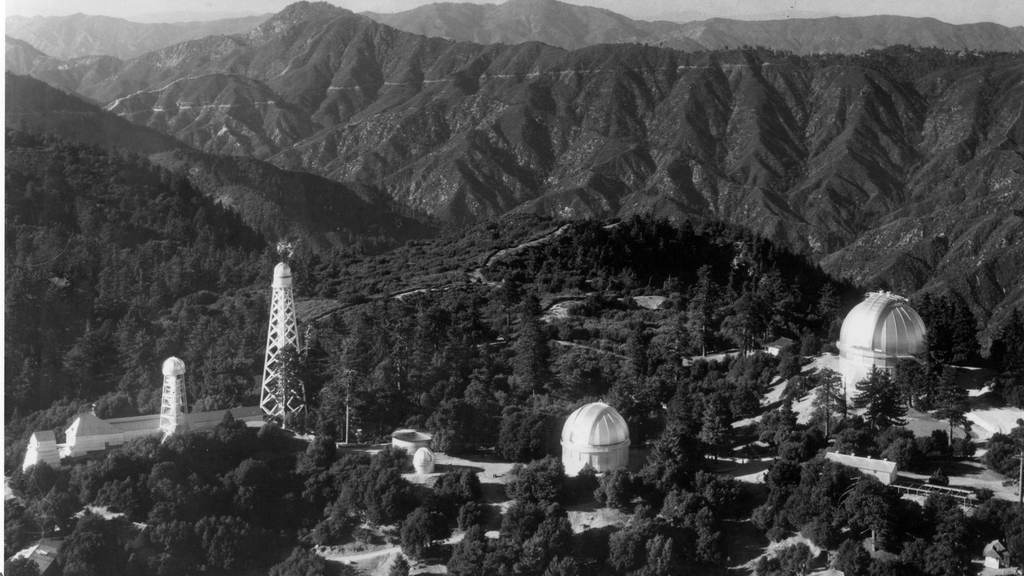

In the intervening years, Carnegie established itself as a giant in astronomy. The institution's Mount Wilson Observatory, founded in 1904 in the mountains above Pasadena, became home to the world's largest telescope. Here, Edwin Hubble would discover the universe and the fact that it is expanding, fundamentally changing our understanding of the cosmos. Later, Carnegie's partnership with Caltech brought the mighty 200-inch Hale telescope to life at Palomar Observatory, further cementing the institution's reputation as a pioneer in building the world's most powerful astronomical instruments.

Yet the southern skies remained out of reach. Legendary Carnegie astronomers like George Ellery Hale, the visionary behind Mount Wilson, and his successor, Walter Adams, periodically revived calls for a southern observatory, but practical challenges and competing priorities prevented the realization of such a project. As the 1960s dawned, there was still no place for Carnegie’s astronomers to view the southern skies, no place for them to see the center of the Milky Way or the Magellanic Clouds.

Carnegie established itself as a giant in astronomy during the early twentieth century. The institution's Mount Wilson Observatory, shown here in 1932, was home to the world's largest telescope, which Edwin Hubble used to discover the universe, fundamentally changing our understanding of the cosmos. Credit: Carnegie Science/Huntington Library

Carnegie's partnership with Caltech brought the mighty 200-inch Hale telescope to life at Palomar Observatory, further cementing the institution's reputation as a pioneer in building the world's most powerful astronomical instruments. Credit: Caltech Archives

Mount Wilson Observatory

200-inch Hale telescope

The Push for Southern Skies

In 1962, Carnegie astronomers Ira Bowen, Horace Babcock, and Robert Leighton developed a long-term plan for the institution's astronomical facilities that elevated the southern observatory project from aspiration to priority. Their effort was well-timed. The landscape of international astronomy was changing, and both the Associated Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) and the European Southern Observatory (ESO) had recently initiated their own plans for new observatories in the southern hemisphere. In a letter to then-Carnegie President Caryl P. Haskins, Bowen emphasized the competitive necessity of establishing a major southern telescope to maintain the institution's leadership in astronomy.

The decision came down to embracing George Ellery Hale's famous exhortation: "Make no small plans." The astronomers gained support from Carnegie’s leadership and Trustees, who at a special committee meeting in May 1963 urged that high and early priority be given to developing an observatory in the Southern Hemisphere. Later that month, the trustees approved funds for a comprehensive site survey, officially launching the Carnegie Southern Observatory (CARSO) project.

The Search for the Perfect Site

The responsibility for site selection fell to Horace Babcock, who was appointed director of the Mount Wilson and Palomar Observatories in 1964. Babcock was well-suited to the challenge and would go on to play a large role in the creation and early years of Carnegie’s southern observatory. A distinguished astronomer at the peak of his career, with a bent for engineering matters, Babcock would prove himself skilled at dealing with scientists and technicians, the institution’s leadership and trustees, and Chilean officials alike.

In late 1963, Babcock arrived in Santiago for the first site trip, where he set off aboard Chilean army transport for La Serena, a coastal town about 250 miles to the north. His ultimate destination was the barren region inland of La Serena, where dry, stable air and high elevation—which would reduce the atmosphere’s distortion of incoming light—create the perfect conditions for astronomical observation of the sky’s southernmost celestial objects.

Astronomical Seeing Monitors (ASM) were flown in from California for the evaluation process. These instruments, consisting of an 8-inch self-guiding telescope and an electronic recording device, measured the steadiness in position of a star as seen through the Earth’s atmosphere and were used to quantify the astronomical “seeing” of potential sites.

While Chile emerged early as the preferred location, scientific rigor demanded comprehensive evaluation of alternatives. With an ASM in tow, Babcock set off in April 1964 for site visits to New Zealand, which proved too cloudy, and Australia, which was more promising. However, accumulated data soon demonstrated Chile's superior “seeing” for astronomical observation.

Astronomer John B. Irwin, arrived in Chile in June 1964, charged with establishing a permanent presence for onsite testing that he would continue for three years. Initial collaboration with AURA appeared promising, with the consortium offering to sell Carnegie a tract near their Cerro Tololo site and providing access to site test at Cerro Morado, a promising peak within their holdings.

A Carnegie group in La Serena, Chile in 1965. Horace Babcock, who oversaw the Carnegie southern observatory project, is pictured second from the left and John Irwin, who conducted three years of site testing in Chile, is picture on the far right. Credit: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, John Irwin Slide Collection

Astronomical Seeing Monitors, which measured the steadiness in position of a star as seen through the Earth’s atmosphere, were used to quantify the astronomical “seeing” of potential sites. Credit: Carnegie Science

While Chile emerged early as the preferred location, scientific rigor demanded comprehensive evaluation of alternatives, including New Zealand and Australia. However, accumulated data soon demonstrated Chile's superior “seeing” for astronomical observation. This image shows a site visit to Mount Serle, Finder Range, Australia. Credit: Carnegie Science

Carnegie group in Chile

Astronomical Seeing Monitor

Australia

Las Campanas: The Chosen Peak

However, a pivotal development occurred in July 1966 when Irwin drove north from Cerro Morado to scout a promising ridge marked on his map as "Campanita." His initial reconnaissance, followed by a September summit expedition to climb to the top of the 8,000-foot peak, revealed promising characteristics, including level ground and potential water sources. He concluded that the site “looks like a real possibility.”

On Babcock’s next visit to Chile in October 1966, he and Irwin made the 5.5-hour round trip trek to the top of the peak, now correctly identified as Las Campanas— “the bells,” likely named for the unique ringing sound certain rocks at the peak make when they are struck. (The true Campanita, “little bell,” is a lower peak situated two miles to the west.) Standing on that remote mountaintop, Babcock recognized the promise of the site. Its remoteness guaranteed dark skies free from light pollution, while its position at the southern end of the Atacama Desert promised the driest, clearest air on Earth.

Over the following two years, Las Campanas evolved from a promising site to Carnegie's preferred location. By November 1968, after another visit to Las Campanas, Babcock made up his mind to recommend that Carnegie make a final decision to build its southern observatory at Las Campanas.

Stopping in Santiago on his return journey, Babcock was surprised to learn that earlier efforts to meet with the Chilean president had borne fruit, and he was scheduled to speak with President Eduardo Frei the following morning. That November 19 meeting would prove decisive for the project’s future. Babcock described Carnegie’s five-year testing efforts to a receptive Frei and mentioned that the institution might seek property rights for land around Las Campanas, which was at that time owned by the Chilean government.

According to a retelling of the events, “To Babcock’s surprise, Frei picked up the telephone and said to his Minister of Land that he wanted an agreement to be rapidly completed to Carnegie’s desires. Putting down the telephone, Frei told Babcock that ‘the land is yours. You can telephone to the United States to start construction of the telescope immediately.’”

Things had moved unexpectedly quickly—Babcock hadn’t even had prior authority to commit the institution to this direction at the time—but Carnegie seized the remarkable opportunity. Negotiations proceeded smoothly, and the purchase of 50,000 acres at Las Campanas was completed in July 1969. Las Campanas Observatory was born.

John Irwin at Las Campanas in October 1966. Irwin’s initial reconnaissance of Las Campanas, followed by a summit expedition to climb to the top of the 8,000-foot peak, revealed promising characteristics. He concluded that the site “looks like a real possibility.” Credit: Carnegie Science

The remoteness of Las Campanas guaranteed dark skies free from light pollution, while its position at the southern end of the Atacama Desert promised the driest, clearest air on Earth. Credit: Carnegie Science

Horace Babcock’s November 1968 meeting with President Eduardo Frei would prove decisive for the future of Carnegie’s southern observatory project. During the meeting, pictured here, President Frei assured Babcock that the Government of Chile would support the Carnegie observatory at Las Campanas. Credit: Carnegie Science

Irwin at Las Campanas

Las Campanas

Babcock and Frei

From Barren Mountaintop to World-Class Observatory

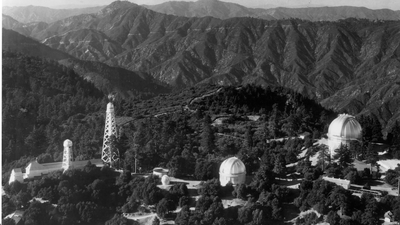

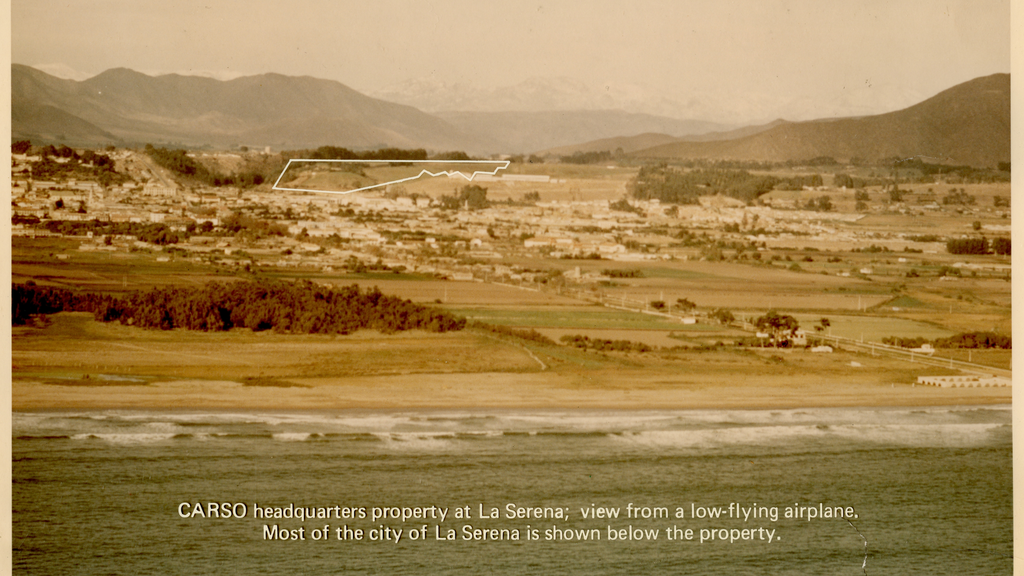

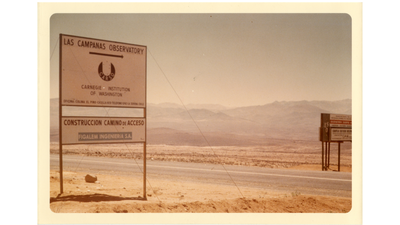

The transformation of the barren mountaintop into a world-class observatory was soon underway. Babcock signed a new cooperative agreement with the University of Chile under the auspices of the Chilean Ministry of Foreign Affairs for entry of Carnegie staff and equipment and for future cooperation in using the telescopes. The institution purchased a plot of land in La Serena known as El Pino as a site for a future administrative office. At Las Campanas a 20-mile access road was carved through the desert, a reliable water supply was developed, and buildings rose from the rocky ground.

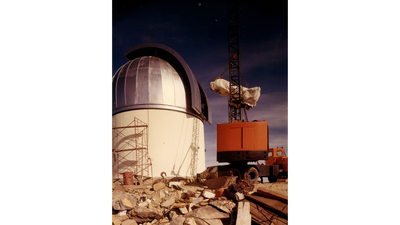

By 1971, Carnegie's first telescope at Las Campanas was ready for dedication. The 1-meter (40-inch) Swope telescope, named for astronomer Henrietta Swope, whose generous 1967 gift was used for site development and the purchase of the telescope, saw first light the following year.

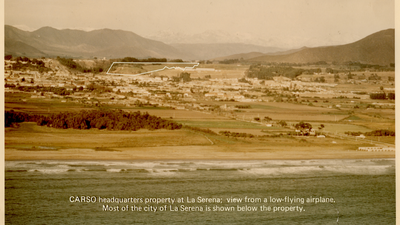

The institution purchased a plot of land in La Serena known as El Pino as a site for a future administrative office. The property is shown here viewed from a low-flying airplane with most of the city of La Serena shown below the property. Credit: Carnegie Science

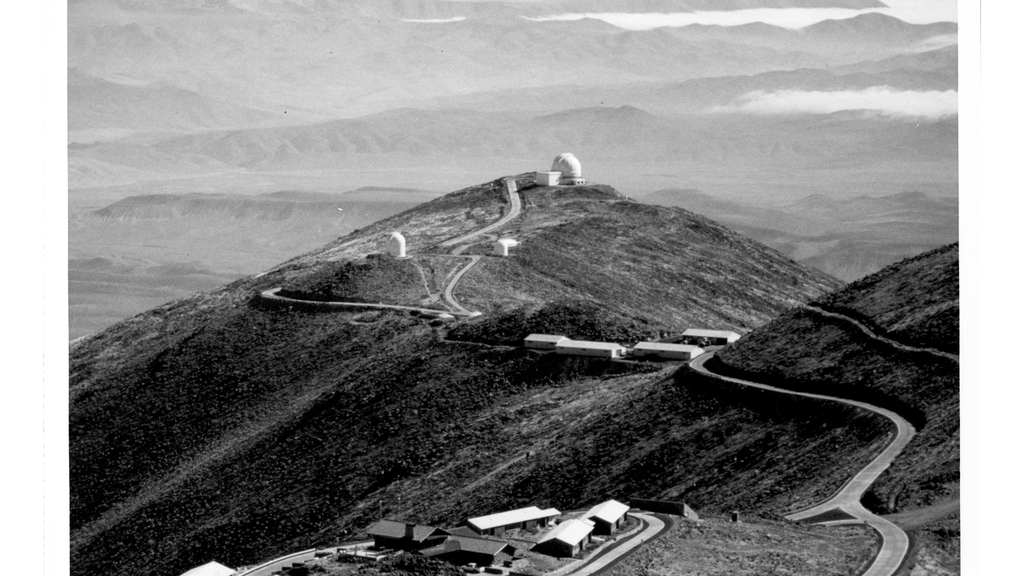

The transformation of the barren Las Campanas mountaintop into a world-class observatory was soon underway. A 20-mile access road was carved through the desert, a reliable water supply was developed, and buildings rose from the rocky ground. Credit: Carnegie Science

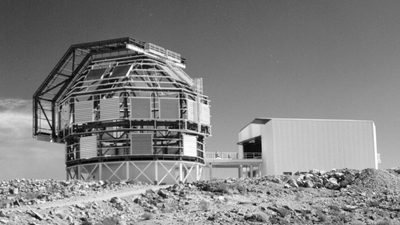

The 1-meter Swope telescope under construction at Las Campanas Observatory. The telescope would be ready for dedication by 1971 and would see first light the following year. Credit: William C. Miller/Carnegie Science

Astronomer Henrietta Swope arriving at Las Campanas Observatory in 1976. The 1-meter Swope telescope was named for Swope, who’s generous 1967 gift was used for site development and the purchase of the telescope. Credit: Carnegie Science

El Pino

Las Campanas construction

Swope telescope

Henrietta Swope

Even before the Swope telescope was finished, construction of a second telescope had begun, this one designed entirely by Carnegie astronomers. The 2.5-meter (100-inch) Irénée du Pont telescope, built with a $1.5 million donation from Carnegie trustee Crawford Greenewalt and his wife, Margaretta, was dedicated in 1976 with first light the following year. (Greenewalt was, at the time of his donation, chairman of the du Pont board. The telescope was named after Margaretta’s father.)

Babcock had originally planned to build a 5-meter telescope at Las Campanas to rival the Hale instrument at Palomar. But when the Ford Foundation turned down his application, funding became an issue. The Greenewalt donation enabled the institution to go forward, though on a smaller scale.

By the late 1970s, with more resources flowing to Las Campanas, Carnegie decided it was time to end its long-term relationship with Caltech. In 1979, the two institutions severed their formal agreement, and the Mount Wilson and Palomar Observatories became the Mount Wilson and Las Campanas Observatories. In 1986, the institution relinquished management of its historic telescopes on Mount Wilson, which were no longer equipped to conduct deep-sky observing due to light pollution from the nearby metropolis. This marked the transition of Carnegie's astronomy program from its California roots to its new focus on the pristine skies of Chile.

Even before the Swope telescope was finished, construction of a second telescope had begun. The 2.5-meter (100-inch) Irénée du Pont telescope was dedicated in 1976 with first light the following year. Credit: Carnegie Science

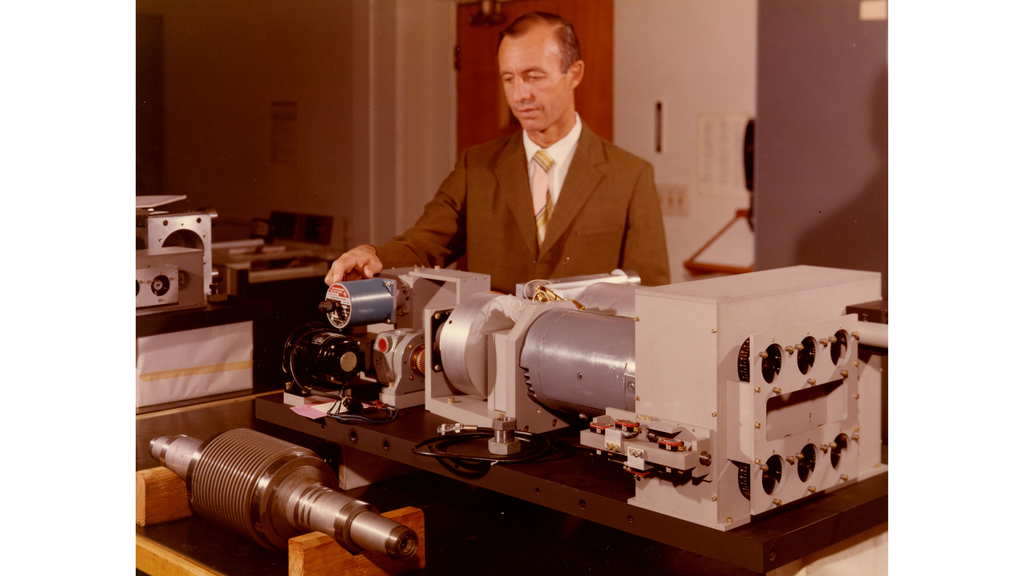

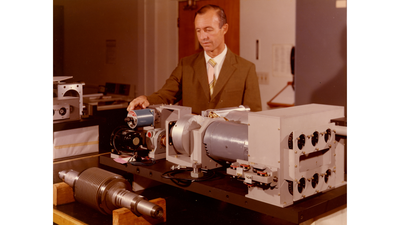

The du Pont telescope was designed entirely by Carnegie astronomers. Engineer Richard Haskell is shown here with the telescope’s right ascension drive in 1973. Credit: Carnegie Science

The du Pont telescope was dedicated in 1976 and saw first light the following year. Credit: Carnegie Science

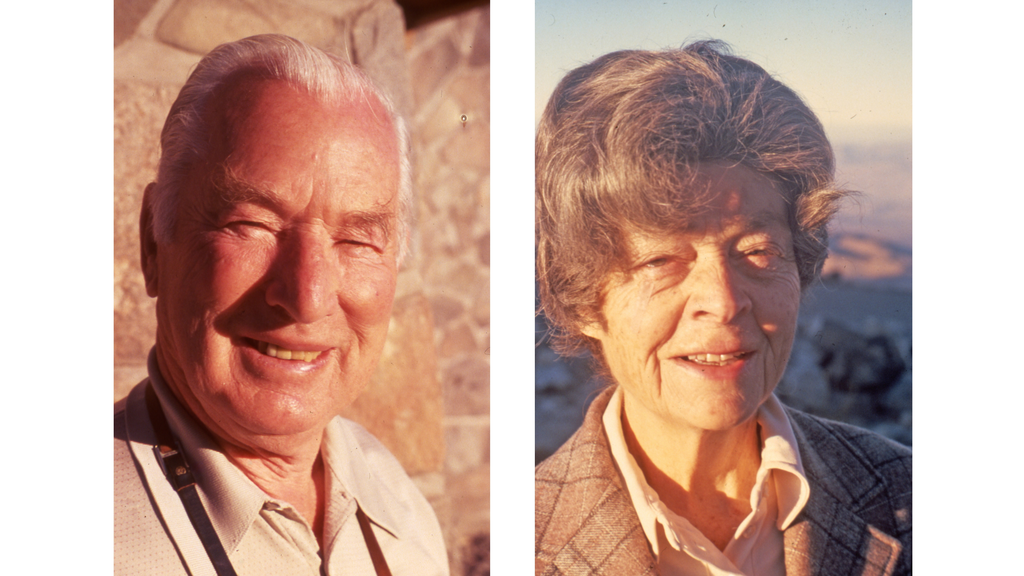

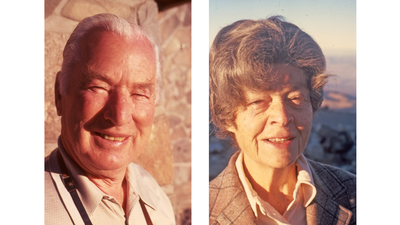

The du Pont telescope was built with a $1.5 million donation from Carnegie trustee Crawford Greenewalt and his wife, Margaretta. The telescope was named after Margaretta’s father. Credit: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, John Irwin Slide Collection

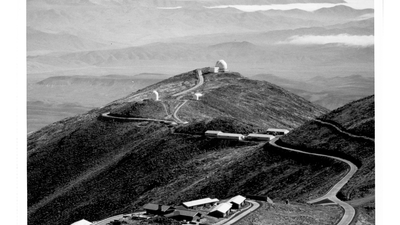

Aerial view of Las Campanas Observatory in 1982. By the end of the 1980s, Carnegie would withdraw from Palomar and Mount Wilson Observatories, focusing its astronomy program on the pristine Atacama Desert skies. Credit: Carnegie Science

du Pont telescope construction

du Pont telescope design

du Pont telescope

Crawford and Margaretta Greenewalt

Las Campanas Observatory

The Magellan Project

With Carnegie fully committed to its southern site, the 1990s brought Las Campanas Observatory’s most ambitious project yet: the Magellan telescopes. These twin 6.5-meter giants, constructed on Cerro Manqui about 100 meters higher than the du Pont telescope, represented the cutting edge of telescope technology.

The Magellan project embodied a new model of astronomical collaboration, bringing together scientists from Harvard University, MIT, and the Universities of Arizona and Michigan. The Walter Baade Telescope (named after the former Carnegie astronomer) and the Landon Clay Telescope (named after a businessman and philanthropist) saw first light in 2000 and 2002 respectively and have since cemented Las Campanas' reputation as a premier site for cutting-edge astronomical research.

The 1990s brought Las Campanas Observatory’s most ambitious project yet: the 6.5-meter Magellan telescopes. This aerial view shows the flattened top of Manqui peak, the site of the future Magellan telescopes, in 1993. Credit: Carnegie Science

Construction of the Magellan Baade telescope enclosure at Las Campanas Observatory in 1996. Credit: Frank Perez/Carnegie Science

The completed Magellan Baade telescope dome and the Magellan Clay telescope under construction at Las Campanas Observatory in 1999. Credit: Carnegie Science

The Magellan Baade telescope mirror suspended over the mirror cell with Magellan Project Manager Matt Johns (left) and Carnegie’s Frank Perez (right) looking on. Credit: Carnegie Science

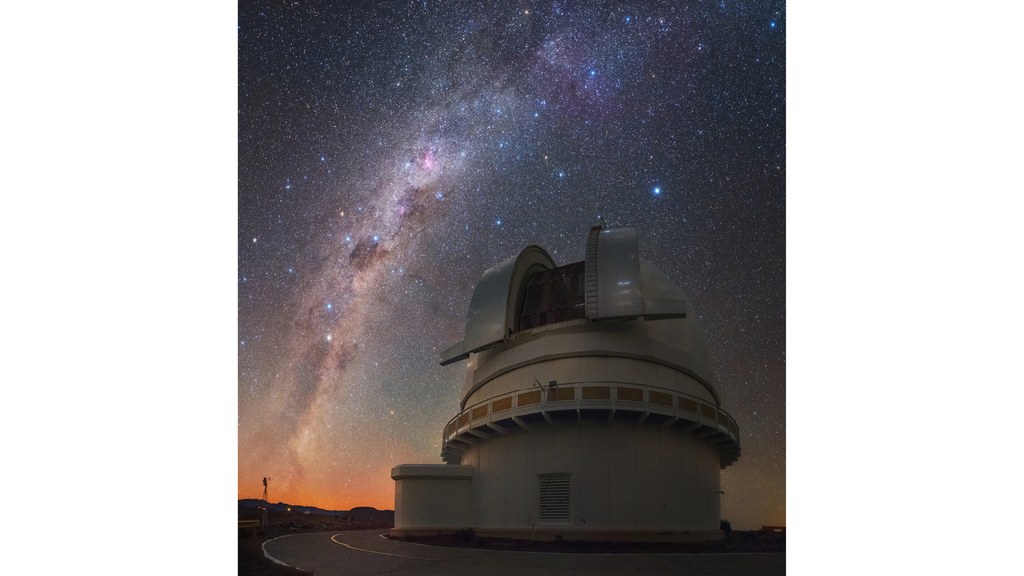

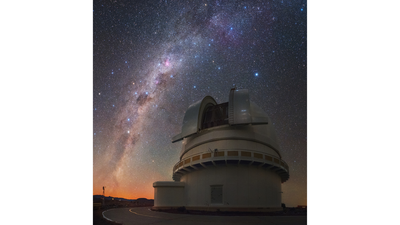

The completed Magellan Clay telescope today. The Walter Baade telescope and the Landon Clay telescope saw first light in 2000 and 2002 respectively. Credit: Yuri Beletsky

Magellan telescopes site

Magellan Baade construction

Magellan Clay construction

Magellan Baade mirror

Magellan Clay telescope

A Living Legacy

In the years since its founding, Las Campanas Observatory has developed into one of the premier astronomical observing sites in the world. Today, Carnegie astronomers, along with their colleagues around the world, keep the telescopes in operation nearly every night of the year, taking advantage of the Atacama Desert's extraordinary atmospheric conditions.

The observatory continues to evolve with advancing astronomical technology. In 2023, the Local Volume Mapper was constructed at Las Campanas Observatory as part of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey's fifth generation, enabling new research on the cosmic ecosystem surrounding the Milky Way galaxy. The facility consists of four custom-built telescopes that capture visible light from the night sky with unprecedented speed, channeling it through 2,000 optical fibers to a suite of three spectrographs for detailed analysis.

But Las Campanas’s greatest chapter may still lie ahead. The Giant Magellan Telescope, now under construction at Las Campanas Observatory, will dwarf all previous instruments with its revolutionary design incorporating seven 8.4-meter mirrors working as one. When completed, this next-generation telescope is poised to transform the field of astronomy. From unveiling the intricate details of distant exoplanets to shedding light on the elusive nature of dark matter, the Giant Magellan Telescope promises a treasure trove of discoveries. As the Giant Magellan Telescope takes shape on the desert mountaintop, it carries forward the same spirit of discovery that drove Carnegie's astronomers to venture into the Chilean desert more than half a century ago.

Rendering of the Giant Magellan Telescope now under construction at Las Campanas Observatory. When completed, this next-generation telescope is poised to transform the field of astronomy. Credit: Giant Magellan Telescope – GMTO Corporation

The Milky Way above the Local Volume Mapper at Las Campanas Observatory. Constructed in 2023 as part of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey's fifth generation, the Local Volume Mapper enables new research on the cosmic ecosystem surrounding the Milky Way galaxy. Credit: Las Campanas Observatory

The Magellan Baade and Clay telescopes at Las Campanas Observatory. Credit: Yuri Beletsky

The du Pont telescope at Las Campanas Observatory. Credit: Yuri Beletsky

The Swope telescope at Las Campanas Observatory. Credit: Yuri Beletsky

Giant Magellan Telescope

Local Volume Mapper

Magellan telescopes

du Pont telescope

Swope telescope

Bibliography

Carnegie Institution of Washington. “That Special Mountain.” Carnegie Evening Booklet, 1986.

Leverington, David. Observatories and Telescopes of Modern Times: Ground-Based Optical and Radio Astronomy Facilities since 1945. Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Sandage, Allan. Centennial History of the Carnegie Institution of Washington: The Mount Wilson Observatory. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Trefil, James and Margaret Hindle Hazen. Good Seeing: A Century of Science at the Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1902- 2002. Washington, D.C.: Joseph Henry Press, 2002.

Edmondson, Frank K. AURA and Its US National Observatories. Cambridge University Press, 1997.