Louis Bauer, DTM’s founding Director, was an eclipse veteran. In May 1900, four years before the Department was established, Bauer organized the first systematic observations aimed at detecting geomagnetic effects of a solar eclipse.

Two decades later, with the experience of multiple eclipses under his belt, Bauer confidently asserted: “There cannot be any doubt that the Earth’s magnetic field is subject to an appreciable magnetic variation during a solar eclipse.”

For the transcontinental eclipse of June 8, 1918, Bauer orchestrated a coast-to-coast observing program, stationing Carnegie teams from Washington State to the Gulf Coast. Bauer witnessed the spectacle from 11,800 feet up in the Rocky Mountains. A few years earlier, Bauer expressed the exhilarating feeling of witnessing a total solar eclipse. “Words will inadequately describe the mingled feelings one has when the supreme moment arrives for which more or less extensive preparations have been made,” he wrote about seeing totality in Samoa in 1911.

The end of WWI in 1918 meant the reopening of international travel and renewed research opportunities. Bauer’s increasingly ambitious campaigns followed, including the eclipse of May 29, 1919, which was eagerly anticipated as a test for Einstein’s new (1916) theory of general relativity. British astronomers would travel to Brazil and Principe island off the coast of West Africa in search of the predicted gravitational bending of starlight passing near the Sun.

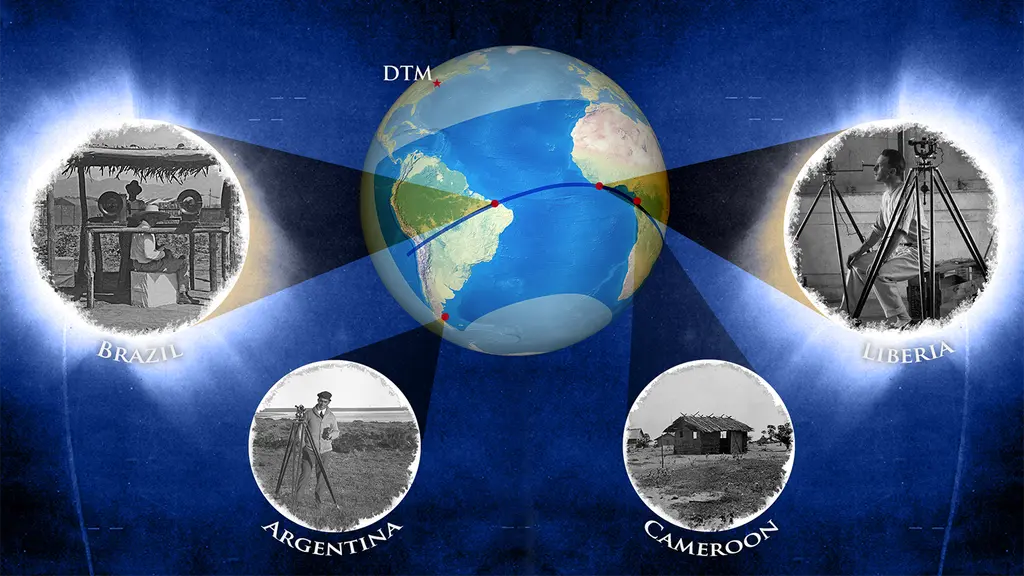

Seeing another opportunity to search for minute, temporary changes in the geomagnetic field as the Moon’s shadow swept across the Earth—and hedging his bets against problems—Bauer selected observing sites on two continents. Cape Palmas, Liberia, and Sobral, Brazil would be Carnegie’s principal eclipse stations. Observers positioned outside the path of totality in Peru, Argentina, Cameroon, and Washington D.C. would also collect data. Cooperative arrangements enabled magnetic observatories in a dozen countries to obtain simultaneous observations. Bauer’s experiment would be global.

Bauer and chief assistant H. F. Johnston reached Cape Palmas on May 5 after a 3-week voyage from England. They unpacked instruments for the eclipse and the magnetic survey work nearby. Twenty-two hundred miles to the west, their counterparts Daniel M. Wise and Andrew Thomson arrived in Sobral. Wise and Thomson’s voyage took 45 days after leaving New York on the steamer Hollandia.

Wise had joined DTM in 1913 as an observer and gained valuable field experience over the next six years. He was an apt choice to lead DTM’s work in Brazil.

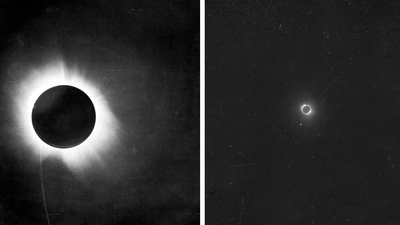

May 29 dawned cloudy in Sobral, but skies cleared as the eclipse commenced. Thomson recorded changes in the electrical properties of the atmosphere under a makeshift shelter. Ironically, manning magnetometers in the basement of a nearby house, Wise may not have seen the eclipse at all. A short distance away, astronomers from Greenwich Observatory photographed the first direct evidence for the “Einstein effect.”

Racing east across the Atlantic at 1500 miles per hour, the Moon’s shadow reached the DTM team at Cape Palmas an hour and a half later. Totality there lasted more than six minutes, providing useful geomagnetic data for the team. However, plans to observe atmospheric-electricity were thwarted by degraded batteries.

After the eclipse, Bauer returned to England to report his results to the Royal Astronomical Society and then to Brussels, where he helped establish the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics.

Another fourteen years would pass after DTM’s “Einstein’s Eclipse” observations for British geophysicist Sydney Chapman to provide a theoretical framework for understanding this elusive phenomenon.

Related Media

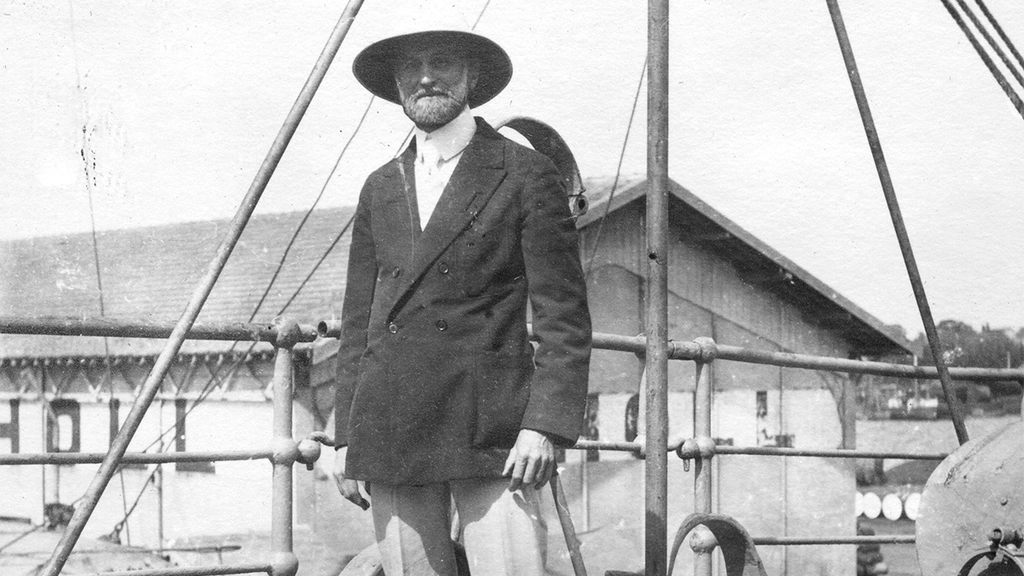

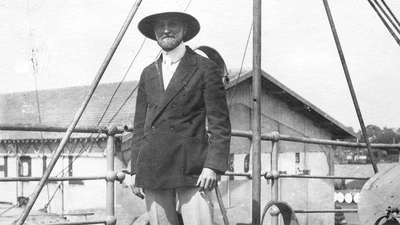

Louis Bauer, founder of Carnegie DTM, en route to Liberia, April 1919.

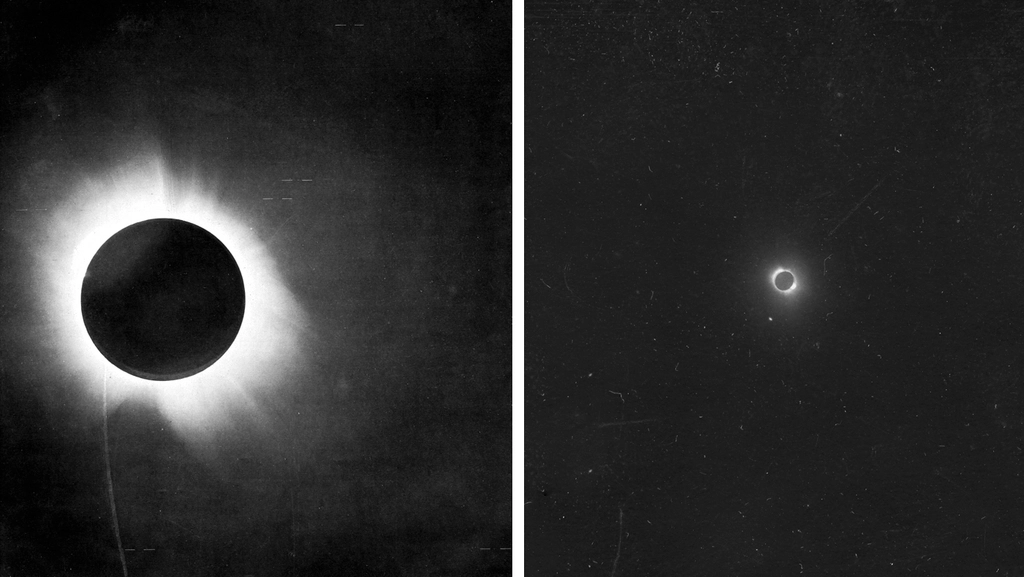

The total solar eclipse of May 29, 1919 as photographed by English astronomer Arthur Eddington at the African island of Principe (left) and by DTM's Louis Bauer and H.F. Johnston at Cape Palmas, Liberia (right).

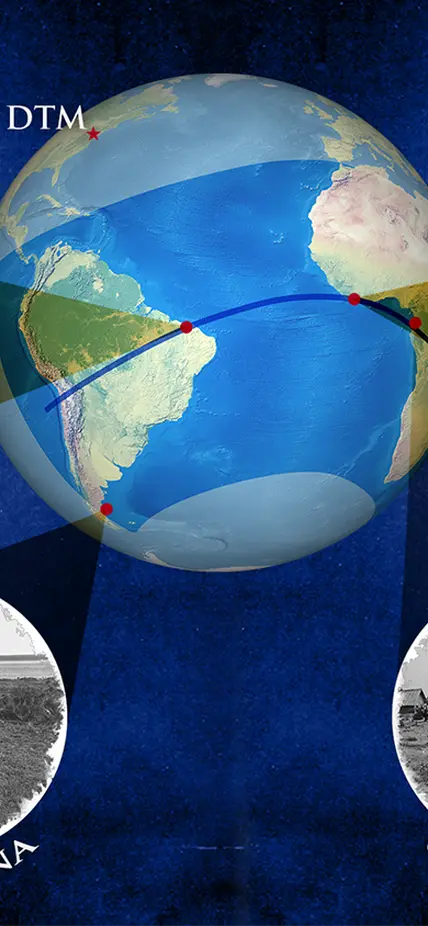

DTM global eclipse expeditions, May 29, 1919, showing the path of totality (solid line) and regions where a partial eclipse could be observed (shadowed region). The Department had eclipse stations along the path of the 1919 eclipse in (from left) Sobral, Brazil; Puerto Deseado, Argentina; Campo, Cameroon; and Cape Palmas, Liberia. Image by Roberto Molar Candanosa/Shaun Hardy, Carnegie DTM.

Louis Bauer

The total solar eclipse of May 29, 1919

DTM global eclipse expeditions