“The wide-ranging scientific prowess represented at Carnegie enables us to develop connections, generate cross-disciplinary ideas, and pivot to new avenues of exploration with speed and agility,” said Vice President for Research Anat Shahar.

At our Earth & Planets Laboratory (EPL), scientists pursue a combination of fieldwork, laboratory experimentation, and mathematical simulations to advance our knowledge of Earth and its place in the Solar System, as well as to discover and characterize distant worlds. Working at the nexus of multiple disciplines—ranging from mineralogy, geochemistry, and geophysics to cosmochemistry and astrobiology—EPL investigators probe how planets, including our own, were born and how they can develop into dynamic celestial bodies.

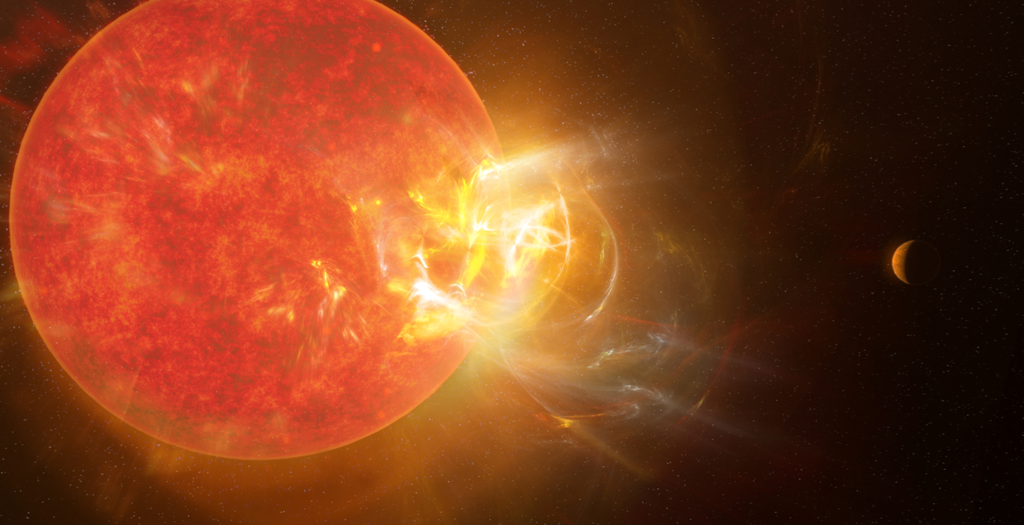

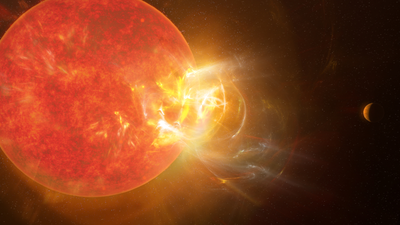

Talk about a noisy neighbor! Research from Carnegie's Alycia Weinberger—as well as former Carnegie Postdoctoral Fellows Meredith MacGregor, now at Johns Hopkins University, and Evgenya Schkolnik, now at Arizona State University—about Proxima Centauri, our Sun’s star next door, offered new details about the twisting tension in its magnetic fields that results in daily flare outbursts, as well as what these streams of energy and particles mean for the habitability of its planets. Credit: NSF/AUI/NSF NRAO/S. Dagnello

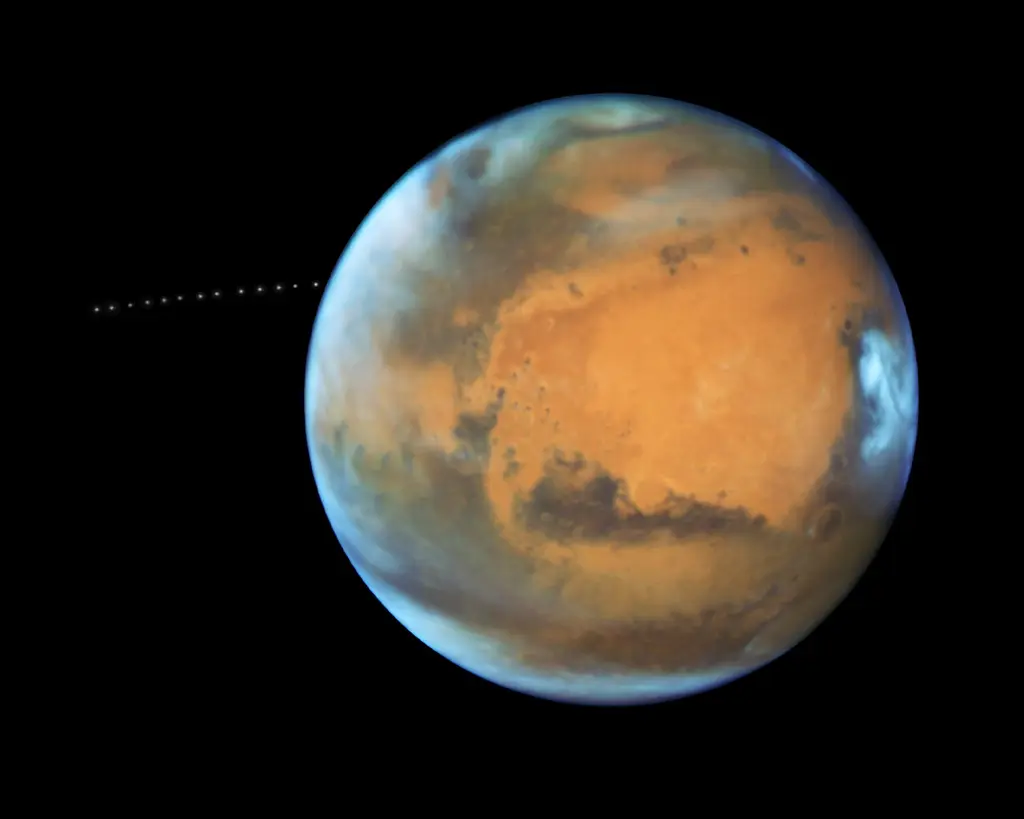

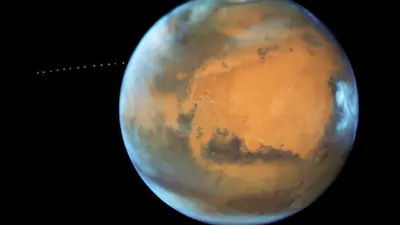

Andrew Steele has been studying the Red Planet for more than two decades—analyzing organic compounds in Martian meteorites and on two rover missions. He was part of a research team that revealed some "extremely interesting mineralogy" associated with reduced carbon in Martian rocks sampled by the Perseverance rover. On Earth, the most likely processes that would create these mineralogical signals are associated with life. However, there are also abiotic ways you can explain these findings. Credit: NASA, ESA, and Z. Levay (STScI)

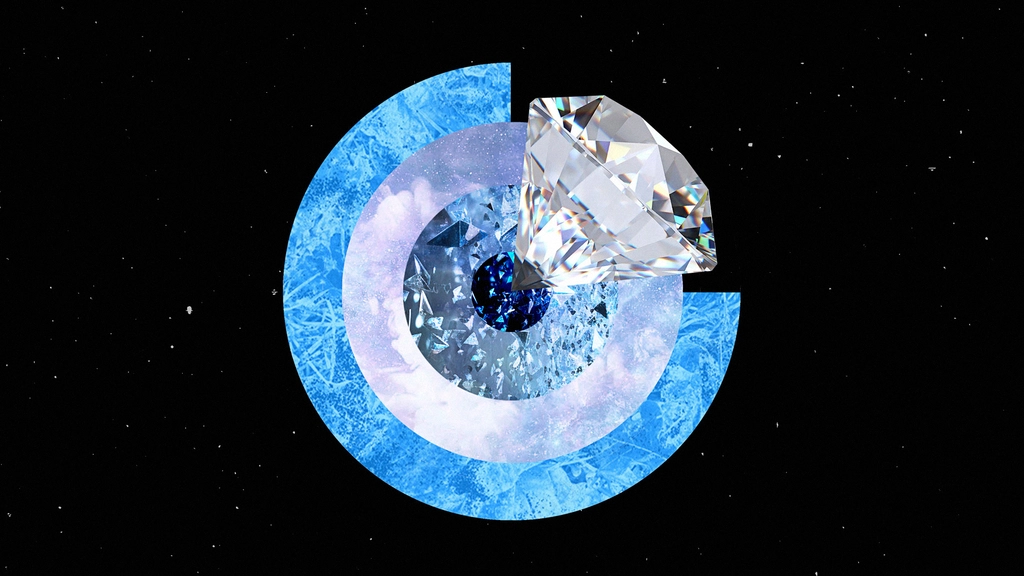

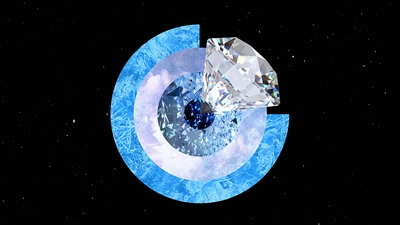

On ice giant planets, diamond forms at shallower depths than previously thought, according to research from Carnegie's Alex Goncharov. Because diamond is denser than the surrounding material, it sinks deeper—a phenomenon sometimes called “diamond rain”—providing an additional heat source, which could drive convection in the ice layer and contribute to these planets’ complex magnetic fields. Although they are not considered habitable, this information about the complex interior dynamics of ice giant planets can help us better understand our own Solar System’s architecture and the evolution of icy worlds. Credit: Navid Marvi/Carnegie Science

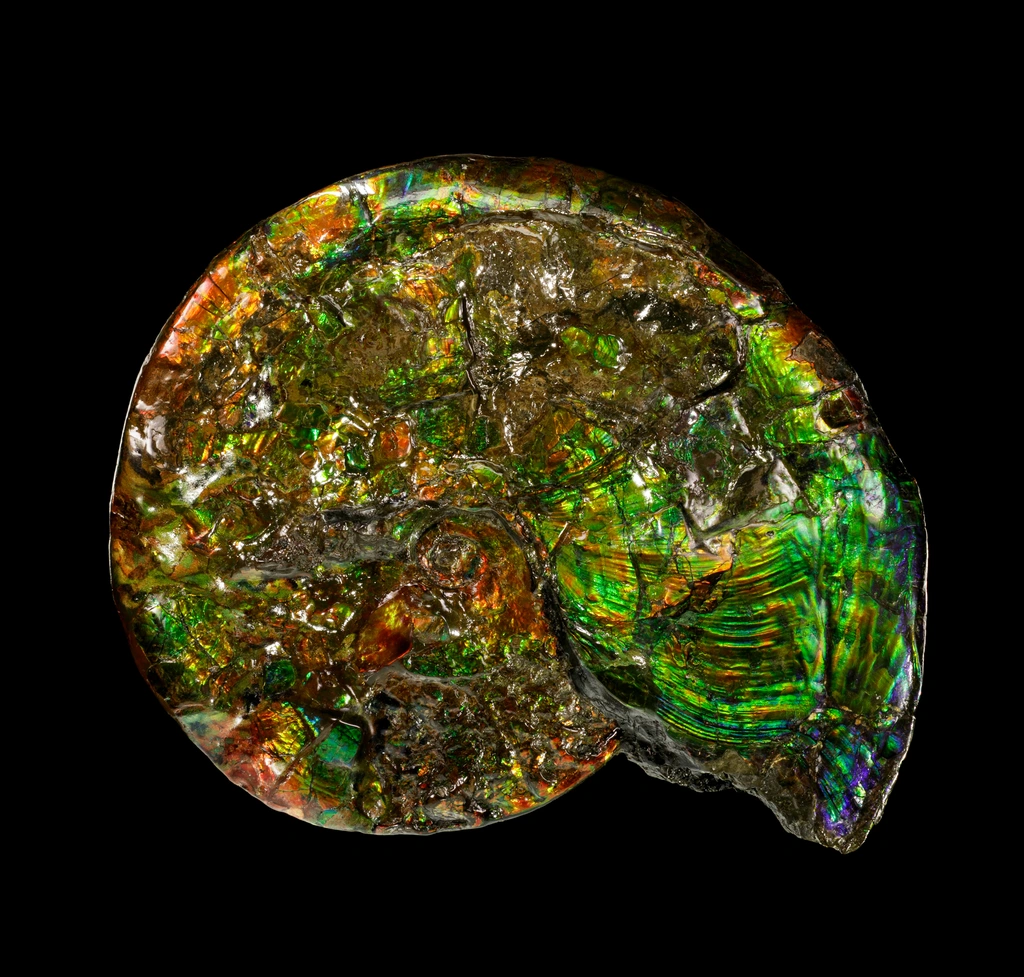

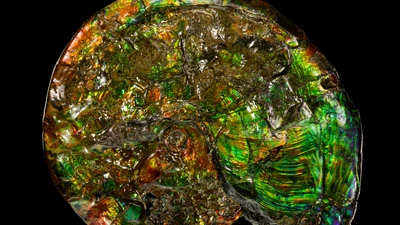

For more than a century, thousands of mineralogists from around the globe have carefully documented “mineral species” based on their unique combinations of chemical composition and crystal structure. Carnegie scientist Robert Hazen and former Carnegie scientist Shaunna Morrison, now at Rutgers University, took a different approach, emphasizing how and when each kind of mineral appeared through more than 4.5 billion years of Earth history. They used extensive database analysis to cluster kindred species of minerals together and distinguish new mineral species based on when and how they originated, rather than solely on their chemical and physical characteristics. Their research helped reconstruct the history of life on our planet, guide the search for new minerals and ore deposits, predict possible characteristics aid the search for habitable exoplanets. Credit: Credit: ARKENSTONE/Rob Lavinsky.

Artist's concept of a stellar flare from Proxima Centauri

While photographing Mars, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope captured a cameo appearance of the tiny moon Phobos on its trek around the Red Planet.

Artist's concept illustrating diamond formation in an ice giant planet interior

Iridescent opalized ammonite

“The breadth and depth of scientific expertise available on our campus creates a cauldron of ideas that allow our researchers to tackle big and exciting questions from a variety of perspectives,” said EPL Director Michael Walter.

Carnegie’s efforts to understand how we got here and whether we are alone in the universe represent an institution-wide undertaking. And EPL scientists comprise the critical link between our astronomers and our biologists.

Discover three ways that our Earth and planetary science researchers are transcending scales to advance Carnegie’s Blueprint for Discovery:

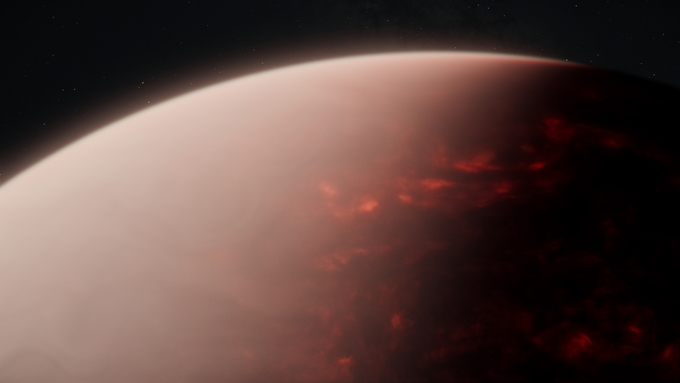

An “Impossible” Atmosphere

TOI-561 b is a rocky world that’s only about twice Earth’s mass but bears little resemblance to our home planet because of its proximity to its host star. Although this star is slightly less massive and cooler than our Sun, TOI-561 b orbits it at one fortieth the distance of Mercury. Conventional wisdom would indicate that this planet is too small and hot to retain an atmosphere long for long after its formation. But recent observations with JWST led by Carnegie’s Johanna Teske and Nicole Wallack indicated that it is surrounded by a thick blanket of gas. The astronomers predicted that TOI-561 b is a “wet lava ball” in which equilibrium is maintained between the atmosphere and a magma ocean—gases are released from the interior, join the atmosphere, and then are sucked back down into the magma. Their work represents the strongest-ever evidence of an atmosphere around a rocky exoplanet.

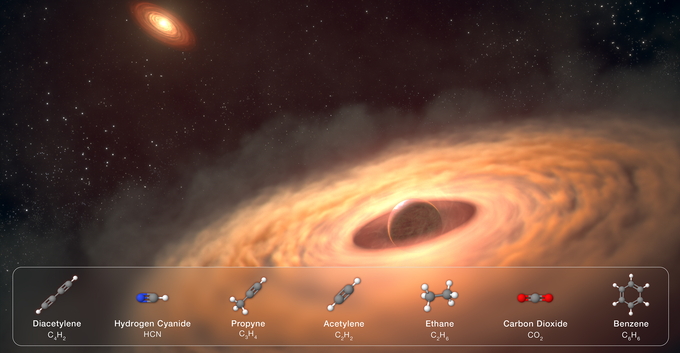

Where Moons Are Born

Circumplanetary disks are a byproduct of the formation process by which giant planets are born from the gas and dust surrounding a young star. These remnants of planetary building blocks constitute a reservoir of material that accretes onto the baby planet and can give rise to moons. But because they are faint and exist in such close proximity to their host stars, these circumplanetary disks have been very challenging to study. Carnegie’s Sierra Grant and Gabriele Cugno of the University of Zurich recently made the first-ever detailed observations of one of these moon-forming disks and characterized its chemical composition in detail. Their JWST observations revealed carbon-rich materials in the disk of a proto-gas giant called CT Chamaeleontis b. Grant and Cugno’s findings could help explain why Jupiter’s moons have such strikingly diverse habitats—a range that includes both the oceanic Europa and the carbon-rich Titan.

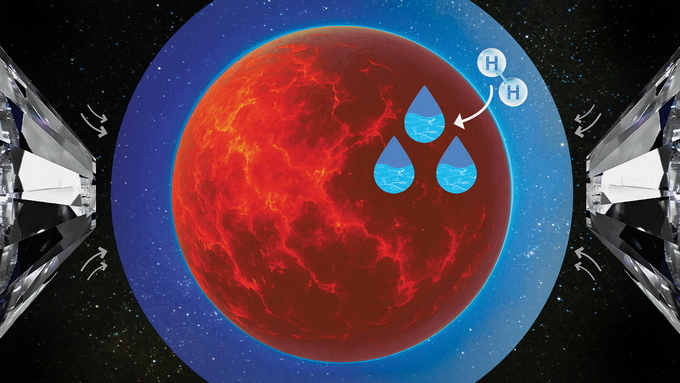

Water Created By Planet Formation

Our galaxy’s most abundant type of planet could be rich in liquid water due to formative interactions between magma oceans and primitive atmospheres during their early years. Recent experimental work led by Carnegie’s Anat Shahar and former Carnegie Postdoctoral Fellow Francesca Miozzi, now at ETH Zürich, demonstrated that large quantities of water are created as a natural consequence of planet formation. Mathematical modeling research had demonstrated that interactions between atmospheric hydrogen and iron-bearing magma oceans during planet formation could produce significant quantities of water. However, comprehensive experimental tests of this proposed source of planetary water had not previously confirmed this possibility. Shahar and Miozzi’s experimental environment mimicked a critical phase of the evolutionary process for rocky planets. They showed that significant quantities of water are created and a copious amount of hydrogen is dissolved into the planet’s magma melt. Their paper constitutes a major step forward in how we think about the search for distant worlds capable of hosting life.