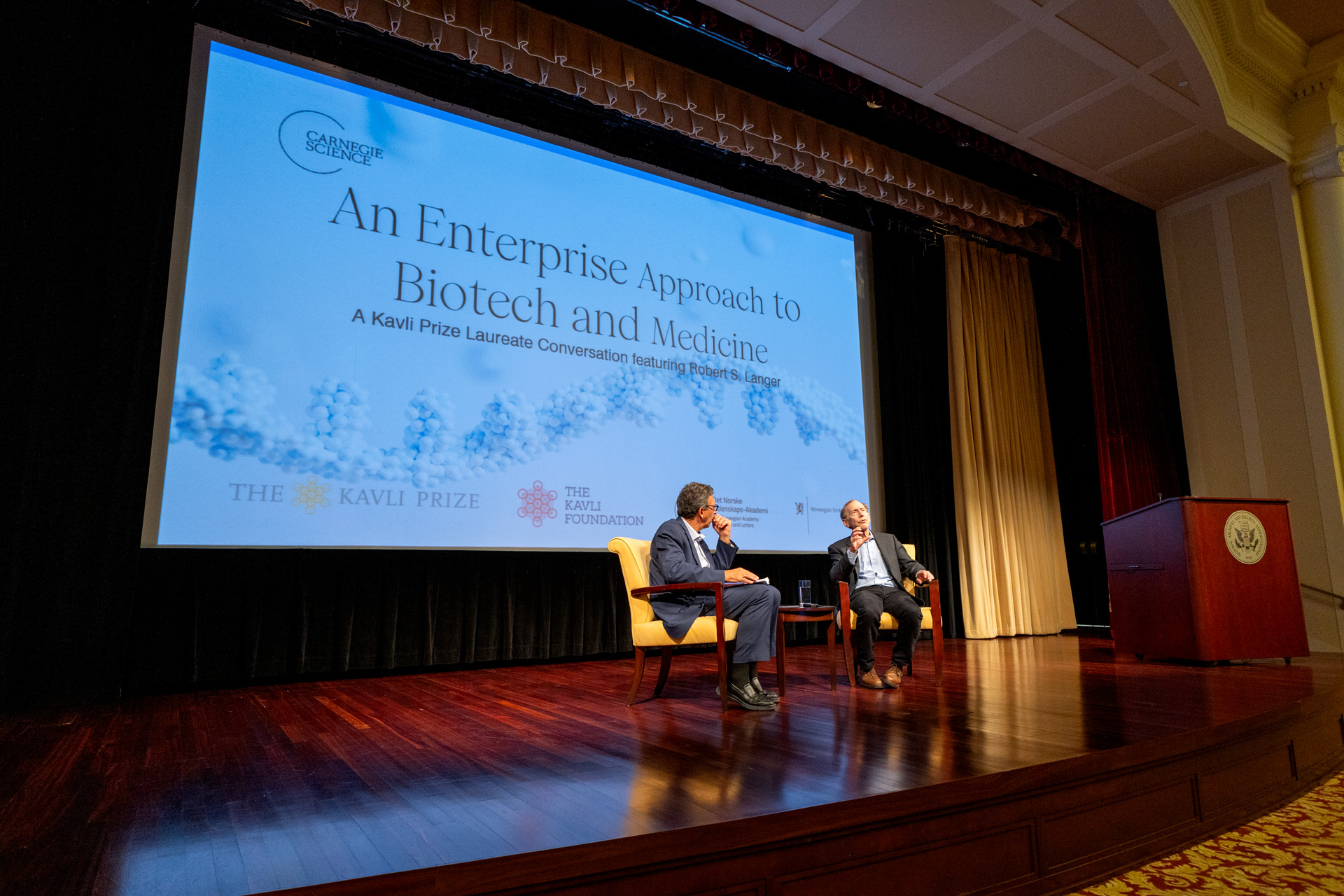

Celebrated chemical engineer, Moderna co-founder, and MIT professor Robert Langer shared his unconventional path to success and a glimpse into the future of cancer treatment and regenerative medicine at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., Wednesday evening. More than 100 attendees, including researchers, science enthusiasts, funders, students, and Langer Laboratory alumni, relished the conversation with this titan of innovation and recipient of the 2024 Kavli Prize in Nanoscience, moderated by The George Washington University professor and longtime CNN reporter Frank Sesno.

Part of Carnegie Science’s hallmark Capital Science Evening outreach program, “An Enterprise Approach to Biotech and Medicine” was one installment in a continuing series of conversations with Kavli Prize laureates. Then-Carnegie Science President Eric D. Isaacs and Kavli Foundation President Cynthia Friend both delivered introductory remarks.

“Professor Langer has taken nanoscience and translated it into some remarkable discoveries in science,” Isaacs said. “Google Scholar has said that he is the most widely cited engineer

in history. He has 1,600 publications… and 1,400 patents, so you can ask where he gets the time…Professor Langer is truly a giant among scientists.”

Through the course of the presentation, Langer gave an overview of the research that led to his receiving the award alongside Armand Paul Alivisatos and Chad A. Mirkin earlier this year, and expanded on the personal and professional decisions that contributed to his scientific and business success. Sesno began the conversation by asking Langer to define nanoscience:

“Well, I suppose a classical definition is to say that you're studying something that might have a diameter between one and 100 nanometers, or one and 1,000 nanometers,” Langer explained. “But another way to think about it is on the order of one-one-thousandth the thickness of the human hair. It’s very tiny.”

Langer went on to explain how an interest in science on such a small scale jump started his career under the direction of Dr. Judah Folkman at Boston Children's Hospital in the 1970s. Using bioassays, they together identified the first inhibitors that could prevent the spread of cancer in blood vessels. This introduction to applied nanoscience would set the course for Langer’s pioneering work in developing sustained-release therapeutics to treat illness such as cancer and diabetes, and his further exploration of mRNA as a vehicle for developing and delivering vaccines. His legacy in the latter is perhaps best reflected in the COVID-19 vaccine developed by Moderna, one of several companies he co-founded.

Beyond the research breakthroughs for which Langer has achieved notoriety, the conversation veered into Langer’s views on the scientific enterprise. Langer noted the importance of public and private funding in innovating new therapeutics and expanding our imagination of what is scientifically possible.

Langer also recounted the hurdles he faced early in his career from other budding and veteran scientists, who doubted the concepts that Langer would realize on a global scale. He discussed his decision to leverage his chemical engineering background to explore an untraditional career path in medicine, rather than the energy and materials careers his colleagues typically pursued.

Sesno, himself a science educator and Executive Director of the GW Alliance for a Sustainable Future, asked Langer to evaluate his work as an educator in a long career of astonishing accomplishments.

“What I'm proudest of is how well my students have done,” Langer said. “I'm certainly proud of the science., but I feel when I look at how well my students have done.. I think 26 are in the National Academy of Medicine, 23 in the National Academy of Engineering, three in the National Academy of Sciences… There were professors all over the world, and they've started great companies. I'm very proud of that.”

Langer described a recent reunion for alumni of the renowned Langer Lab at MIT, where hundreds of former students and their families gathered to celebrate his career. Over the course of several days, alumni told stories and expressed the ways Langer influenced their career development.

In a video introduction, Norwegian Academy of Letters and Sciences President Lise Øvreås hinted at Langer’s reputation for mentorship and kindness when recounting Langer’s trip to Norway to accept the Kavli Prize.

“In meetings with Norwegian emerging talents and the press, Langer chose to emphasize how fortunate he has been and the importance of simply being a nice person in science,” she said. “His admirable combination of excellent skills, dedication, and humility makes him a brilliant role model for new generations of scientists and hundreds of them have had the training under his mentorship at the Langer lab.”