Pasadena, CA— The mysterious Blue Ring Nebula has puzzled astronomers since it was discovered in 2004. New work published in Nature by a Caltech-led team including Carnegie astrophysicists Mark Seibert and Andrew McWilliam revealed that the phenomenon is the extremely difficult-to-spot result of a stellar collision in which two stars merged into one.

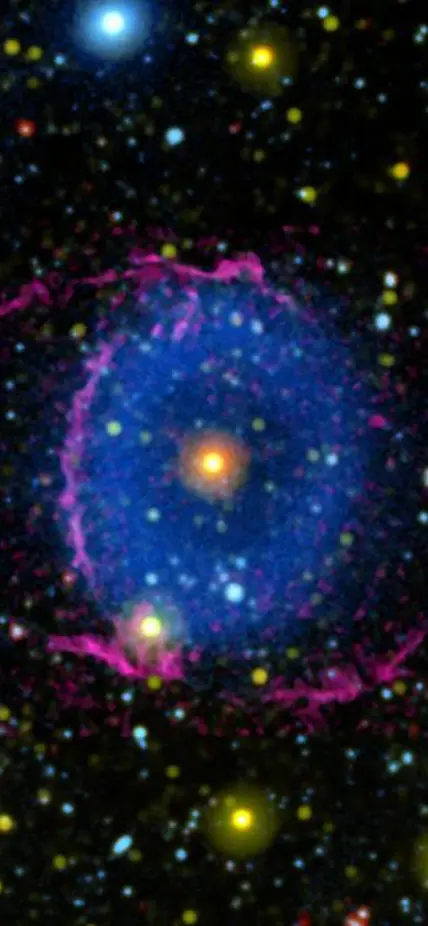

Sixteen years ago, NASA’s Galaxy Evolution Explorer (GALEX) spacecraft discovered a large, faint blob of gas with a star at its center—an object unlike anything previously seen in our Milky Way galaxy. The blob is represented as blue in the ultraviolet images of GALEX—although it doesn't actually emit light visible to the human eye—and careful observations identified two cones of gas ejected from the system that when viewed from our perspective on Earth looks like a ring, resulting in the object being nicknamed the Blue Ring Nebula.

Over the ensuing years, the GALEX team studied the unusual object with multiple Earth- and space-based telescopes, but the more they learned about it, the more mysterious it seemed.

"For quite a long time we thought that maybe there was a planet several times the mass of Jupiter being torn apart by the star, and that was throwing all that gas out of the system," said Seibert, who is a member of Caltech’s GALEX team.

More than a decade after the Blue Ring Nebula’s discovery, the researchers had gathered data on its system from four space telescopes and four ground-based telescopes, as well as pored over historical observations of the star going back to 1895 to look for changes in its brightness over time. They’d also acquired the help of citizen scientists from the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO). But an explanation still eluded them.

Principal investigator for GALEX at Caltech, Chris Martin, and colleague Keri Hoadley recruited Columbia University theorist Brian Metzger, who specializes in modeling cosmic collisions between a variety of objects, including planets and stars, or two black holes.

"It wasn't just that Brian could explain the data we were seeing; he was essentially predicting what we had observed before he saw it," said Hoadley. "He'd say, 'If this is a stellar merger, then you should see X,' and it was like, 'Yes! We see that!'"

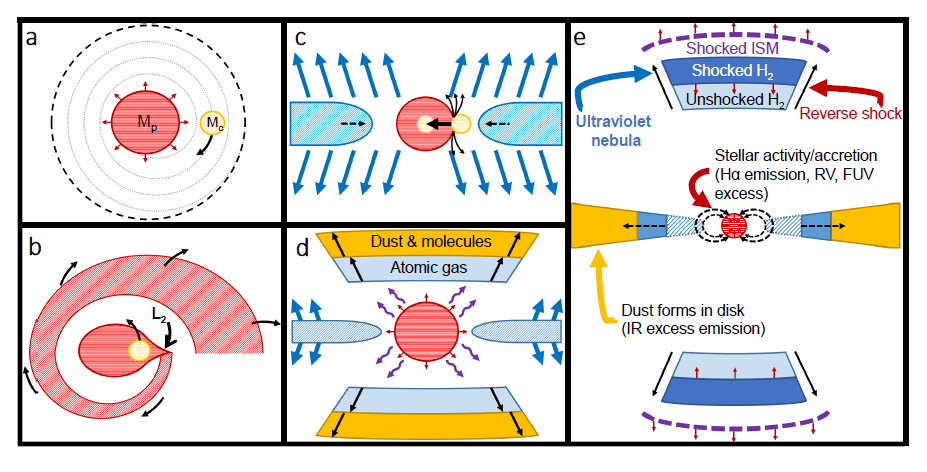

The team concluded that nebula was a relatively fresh stellar merger that likely occurred between a star similar to our Sun and a smaller one only about 100 times the mass of Jupiter.

One of the factors that made the Blue Ring Nebula so difficult to understand is that, for the central star's temperature, the luminosity measured by the European Space Agency's Gaia mission indicates a very young star; whereas, the chemical composition is that of a very old star.

“The merger of two old stars explains the seemingly conflicting observations about the central star’s youthful luminosity and aged chemical makeup,” McWilliam added.

While merged star systems most likely aren't uncommon, they are nearly impossible to study immediately after they form because they're obscured by debris kicked up by the collision. Once the debris has completely cleared—at least hundreds of thousands of years later—they’re challenging to positively identify because they mostly look like non-merged stars.

The Blue Ring Nebula appears to be the missing link: Astronomers are seeing the star system only a few thousand years after the merger, when evidence of the union is still plentiful, and may be the first known example of a merged star system at this stage.

The Blue Ring Nebula appears to be the missing link: Astronomers are seeing the star system only a few thousand years after the merger, when evidence of the union is still plentiful, and may be the first known example of a merged star system at this stage.

Stellar mergers may occur so frequently—as often as once every 10 years in the Milky Way—it’s possible that a sizeable population of the stars we see in the sky were once two.

"We see plenty of binary star systems that haven't merged and we think we've identified stars that merged maybe millions of years ago, but we have almost no data on what happens in between," Metzger said. "We think there are probably plenty of young remnants of stellar mergers in our galaxy, and the Blue Ring Nebula might show us what they look like so we can identify more of them."

Though this is likely the conclusion of a 16-year-old mystery, it may also be the beginning of a new chapter in the study of stellar mergers.

"It's amazing that GALEX was able to find this really faint object that we weren't looking for but that turns out to be something really interesting to astronomers," Seibert said. "It just reiterates that when you look at the universe in a new wavelength or in a new way, you find things you never imagined you would."

__________________

JPL, a division of Caltech, managed the GALEX mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. The mission was developed by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, under the Explorers Program. JPL also managed the Spitzer and WISE missions. In Sept. 2013, NASA reactivated the WISE spacecraft with the primary goal of scanning for near-Earth objects, or NEOs, and the mission and spacecraft were renamed NEOWISE. JPL is a division of Caltech.

The authors acknowledge with thanks the variable star observations from the AAVSO International Database contributed by observers worldwide and used in this research.