On Thursday, November 7, 2019, Kurt Feigl, a professor in the Department of Geoscience at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and current Merle A. Tuve Senior Fellow at DTM presented his Tuve Lecture titled “From Landers to NISAR, (Nearly) 30 Years of Observing Crustal Dynamics by Satellite Radar Interferometry.” In his talk, Feigl discussed the details of interferometric synthetic-aperture radar (InSAR) and presented current applications for the technology.

“Topography” stated Feigl, “is a signal. Changes in topography are rich in information.” This richness of information is what makes InSAR such a powerful tool for understanding our planet.

Since Eratosthenes first measured the circumference of the Earth back in 240 BC, geodesy, the science of measuring Earth’s shape and its changes, has largely been confined to taking individual measurements on the ground. Until recently, measuring the changes to the Earth’s crust (e.g., after an earthquake or similar event) required a lot of field work, covered only limited areas, and collected only a few data points. From these sparse data, scientists can track the changes in Earth’s crust.

In the 1990s, satellites equipped with InSAR allowed geodesists, like Feigl, to measure changes to the planet’s surface from space. With this technology, they can measure displacements with spatial resolution at least a million times better than ground-based techniques. Although ground-truthing the satellite measurements is still needed, InSAR provides rich maps of surface deformation that then can be used to constrain models for the processes driving deformation. With this approach, researchers can estimate parameters such as the depth of the fault responsible for an earthquake or the volume of magma injected into an inflating volcano.

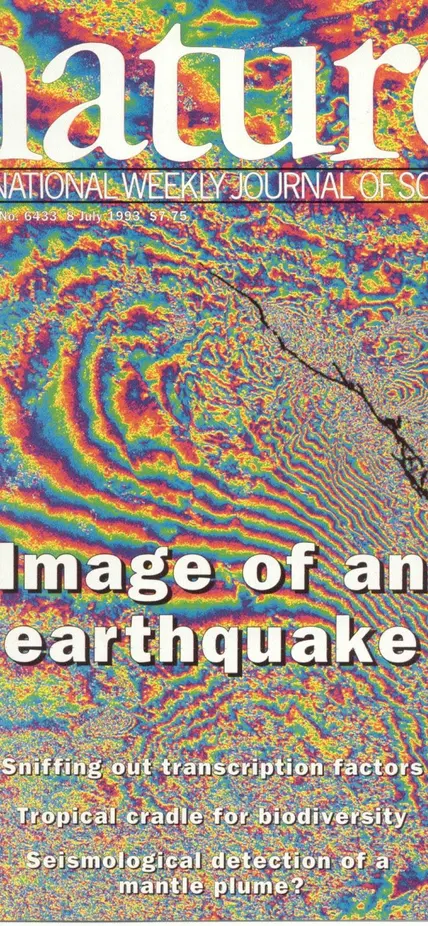

This figure maps the deformation produced by an earthquake. Using InSAR, Feigl and colleagues in a team led by Didier Massonnet at the CNES space agency in France analyzed images before and after the 1992 Landers earthquake in California. As featured in Nature in 1994, each full cycle of rainbow color indicates a displacement of 28 mm of the Earth’s surface. Image Source: Nature Publishing Group

“When we can measure these changes, we can figure out what’s going on inside of the Earth” stated Feigl.

Now, Feigl combines Global Positioning Systems (GPS), satellite radar interferometry, and other remote-sensing tools to measure and model a variety of geophysical processes including those driving earthquakes, volcanoes, and glaciers.

What is a Tuve Lecture?

The DTM Tuve Senior Fellowship started in 1996 in honor of the late Merle A. Tuve, who served as DTM director from 1946-1966. Among his many scientific accomplishments, Tuve supervised the development of the proximity fuze during World War Two, and the design of a pressurized Van de Graaff generator, which achieved energies above 4 MeV. In 1942, he served as founding Director of the Applied Physics Laboratory.

Chosen at the discretion of the director of DTM, recipients of the Tuve fellowship are provided housing support and DTM resources during visits to DTM to work on problems of mutual interest with current staff members at DTM. Support for the fellowship program derives from the initial gift of former staff scientist and DTM Acting Director Tom Aldrich with donations from several DTM alumni and most recently gifts in memory of Erik Hauri. Like Feigl, each Tuve Fellow presents their findings in a culminating lecture as a part of the DTM Tuve lecture series.