Washington, DC—Carnegie Science’s Joseph Gall, called the founder of modern cell biology for his contributions to our understanding of chromosomes and the cellular nucleus, and a widely recognized champion for women in science, died September 12. He was 96.

“Joe had an outsized impact on biology, both through his creative and groundbreaking research and through his mentorship of generations of scientists who went on to be celebrated in their own right,” said Carnegie Science President Eric D. Isaacs. “His bold, boundary pushing approach made him a ‘scientist’s scientist,” perfectly demonstrating how brilliant minds can change the world when given the freedom to pursue their curiosity where it leads.”

Gall, who joined Carnegie Science in 1983, revolutionized our understanding of how chromosomes are organized by showing that most chromosomes contain a single DNA molecule stretching from end to end. In the late 1960s, working with his Yale University graduate student Mary Lou Pardue, Gall developed a powerful technique called in situ hybridization, which allows researchers to locate and map genes on this chromosomal DNA.

This groundbreaking tool also revealed that some specific RNA transcripts localize to precise subregions of the cell that are important for their function. In situ hybridization was among the first techniques to connect individual nucleic acid sequences with the genome as a whole, and helped usher in today's genomic era.

A decade later, his work with graduate student Elizabeth Blackburn revealed the structure of telomeres, a repetitive segment of DNA at the end of each chromosome, which protects the genetic material from damage and ensures it is fully copied prior to cell division. Telomeres have been proposed to play a role in animal longevity, but this remains unproven.

At Carnegie, Gall continued to advance our understanding of activities in the nucleus with research about many aspects of genome transcription and processing.

In 2006, the Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation recognized Gall with its prestigious Special Achievement Award in Medical Science, a prize that is often referred to as the American Nobel. The foundation named him, “among the most distinguished cell biologists in the history of the discipline” and praised his “thoughtful, committed” approach to scientific problem-solving and “high degree of insight and integrity.”

Lasker Award with Blackburn and Greider, 2006

Gall's 95th birthday celebration at Carnegie Science

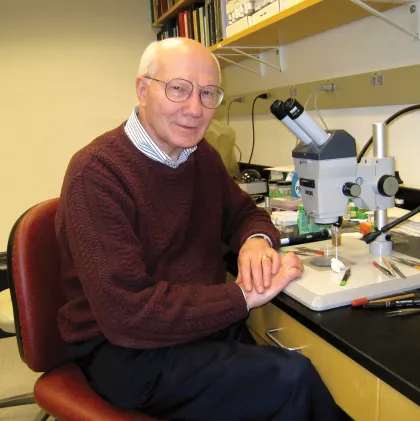

Gall outside the lab at Carnegie Science, 2006

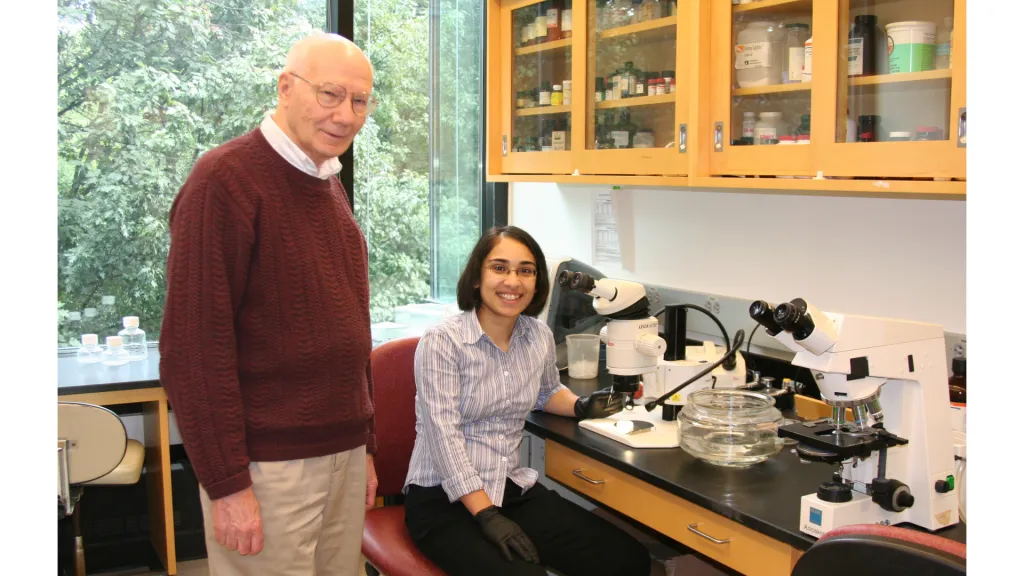

Gall and predoctoral fellow Zehra Nizami, 2009

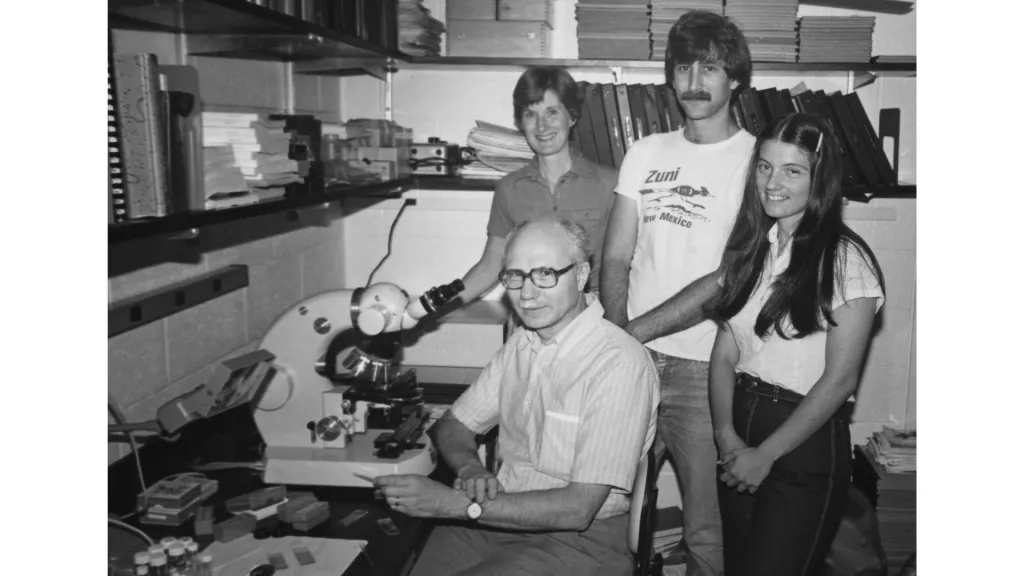

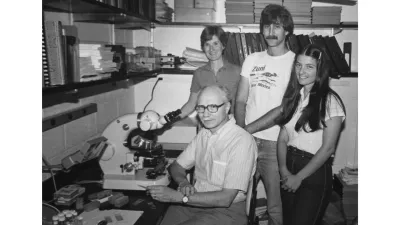

Gall group in the lab at Carnegie Science, 1980s

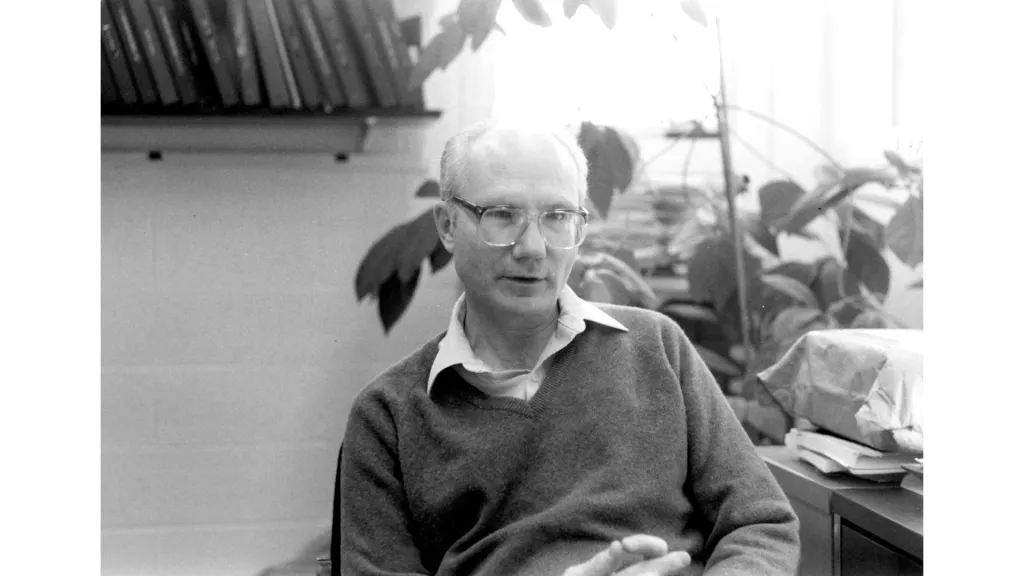

Gall in his office at Carnegie Science, 1985

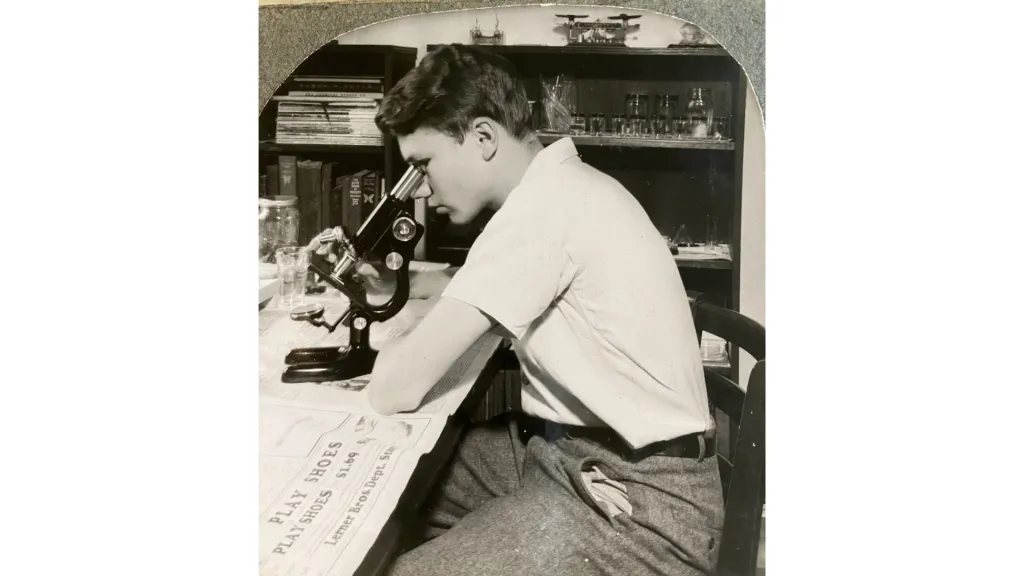

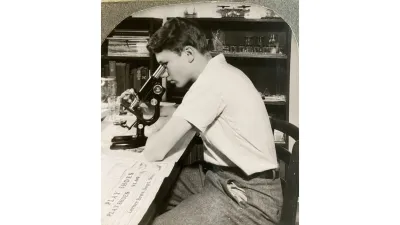

Teen Gall with Microscope

Gall was noted for his broad knowledge of animal, plant and micro-organismal biology.

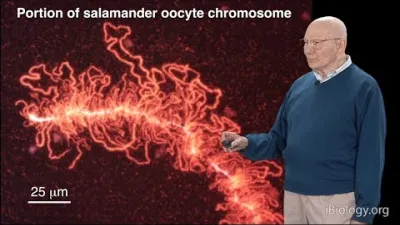

"This depth of understanding enabled Joe to choose a particular species that is ideally suited to investigating a specific problem. He probably published important findings using more different organisms than any of his contemporaries, and in this respect was far ahead of his time,” said longtime Carnegie Science colleague Allan Spradling. “The nucleus of the cell, especially the large nuclei of egg cells used for developmental biology research, attracted much of Joe’s attention and he favored the large chromosomes known as ‘lampbrush chromosomes’ found in frogs and newts whose study inspired many important discoveries.”

Added Yixian Zheng, another developmental biology colleague at Carnegie Science: “Joe always encouraged me to avoid bandwagon science and to follow my own instincts, pursuing biological functions that are understudied, but important.”

Gall stood out from many of his peers in the 1960s and 1970s for mentoring and championing women. His lab was recognized as one of the few places where burgeoning women biologists could get serious training and not be sidelined by male peers.

Several of his former students and postdocs have gone on to acclaim of their own, including election to the National Academy of Sciences and winning major research prizes. Joan Argetsinger Steitz later received a Lasker for her work on messenger RNA and Blackburn and her own student Carol Grieder were awarded the Nobel Prize for the discovery of telomerase, the enzyme that replenishes the telomere after cell division.

“The effect of Joe Gall was multiplied,” Catherine Brady, the author of a book about Blackburn, told The Chicago Tribune in 2009. “It’s like a family tree. With each generation, there are more people.”

At Gall’s retirement symposium in 2020, Blackburn praised “Joe’s supportiveness and kindness to everyone in his lab,” as emphasized the enormous impact he has had on all of his former mentees. “When encountering lab or research related situations, I’ve heard this over and over, we always think: what would Joe do?”

Gall credited his mother, who overcame sexist preconceptions to earn a degree in mathematics, as one of his most important mentors for fostering his early interest in science and the natural world. Growing up, he spent his summers on a farm in Northern Virginia where he collected insects. Over time, this passion grew from homemade butterfly nets supplied by his mother to the gift of a microscope.

The depth of his interest in the field of microscopy never waned. Gall legendarily built the microscope on which he did his own dissertation research at Yale and continued to advance the boundaries of what these instruments can accomplish for decades.

"After much urging, my parents bought me a microscope when I was 14 years old—not one of the toys I had struggled with up to that time, but the real thing," he said in a Carnegie Science interview in 2006.

Rather than going to a local high school, Gall attended and thrived at Woodberry Forest, a boy's boarding school school near Charlottesville, Virginia. After three years, the headmaster thought he was ready to go to college.

Gall received his B.S. from Yale 1949 and went on to complete his Ph.D. in 1952. Between 1952 and 1964, he taught at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, where he became Professor of Zoology. In 1963 he returned to Yale as part of his sabbatical, but before his year was over, he was offered a position as Professor of Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry. In an unusual twist to an academic career, he decided to leave Yale in 1983 to join Carnegie's Department of Embryology so he could conduct research full time.

In addition to the Lasker, Gall was also a recipient of Columbia University’s Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize (together with Blackburn and Greider, both Nobel Laureates) and the American Society of Cell Biology’s top honor, the E.B. Wilson Medal

He is survived by his wife, Diane M. Dwyer; son, Lawrence F. Gall; daughter, Barbara G. Eidel; and three granddaughters Jennifer Barrer-Gall, Lillian Eidel, and Shelby Eidel.

Meet Joseph Gall | Maryland Public Television

Gall the Mentor | 2006 Lasker Koshland Special Achievement Award

Joseph Gall: Keynote Presentation - Retirement Symposium

Joseph Gall - In Situ Hybridization | iBiology