Washington, DC— The amount of time it takes for an ecosystem to recover from a drought is an important measure of a drought’s severity. During the 20th century, the total area of land affected by drought increased, and longer recovery times became more common, according to new research published by Nature by a group of scientists including Carnegie’s Anna Michalak and Yuanyuan Fang.

Scientists predict that more-severe droughts will occur with greater frequency in the 21st century, so understanding how ecosystems return to normal again will be crucial to preparing for the future. However, the factors that influence drought recovery have been largely unknown until now.

“Research has usually focused on the amount of rain and other precipitation that ends the deficit of water that causes a drought, but assessments of drought-recovery need to account for the restoration of normal plant function,” explained Michalak.

The team—including four other alumni of Carnegie Global Ecology research groups William Anderegg (University of Utah), Adam Wolf (Arable Labs Inc.), Deborah Huntzinger (Northern Arizona University), and Maoyi Huang (Pacific Northwest National Laboratory)—used measures of photosynthetic activity to assess drought recovery. Quantifying how long it took for plant productivity to return to normal gave the researchers a better understanding of the longevity of a drought’s effects.

“If another drought arrives before trees and other plants have recovered from the last one, the ecosystem can reach a ‘tipping point’ where the plants’ ability to function normally is permanently affected,” Fang said.

The conditions most-strongly contributing to drought recovery time were precipitation and temperature, they found. Unsurprisingly, better conditions shortened recovery. Temperature extremes, both hot and cold, lengthened it.

Recovery took the longest in the tropics, particularly the Amazon and Indonesia, and in the far north, especially Alaska and the far east of Russia.

Other factors influencing drought recovery included pre-drought photosynthetic activity, carbon dioxide concentrations, and biodiversity.

The team found that drought impacts increased over the 20th century. Given anticipated 21st century changes in temperature and projected increases in drought frequency and severity due to climate change, their findings suggest that recovery times will be slower in the future. A chronic state of incomplete drought recovery may be the new normal for the remainder of the 21st century and the risk of reaching “tipping points” that result in widespread tree deaths may be greater going forward, they say.

Other members of the team include lead author Christopher Schwalm of the Woods Hole Research Center; Joshua Fisher of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory; Franco Biondi of University of Nevada-Reno; George Koch and Kiona Ogle of Northern Arizona University; Marcy Litvak of University of New Mexico; John Shaw of the U.S. Forest Service; Kevin Schaefer of the National Snow and Ice Data Center; Robert Cook and Yaxing Wei of Oak Ridge National Laboratory; Daniel Hayes of University of Maine; Atul Jain of University of Illinois; and Hanquin Tian of Auburn University.

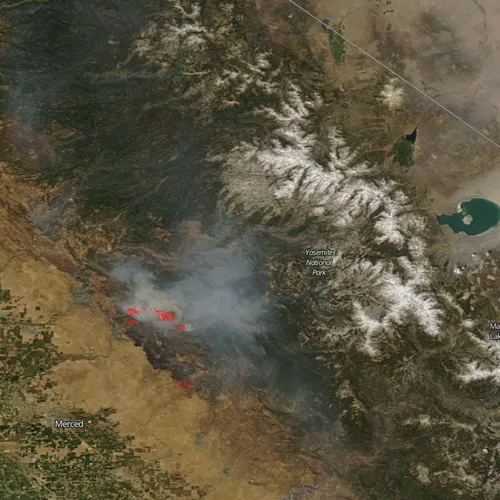

Caption: Forest fires near California’s Yosemite National Park captured by NASA’s Aqua satellite in July 2017. Actively burning areas are shown in red. Image courtesy of NASA MODIS Rapid Response Team.

Top Image Caption: Drought-affected aspen trees in Colorado, courtesy of William and Leander Anderegg. The paper’s authors argue that assessments of drought-recovery need to account for the restoration of normal plant function, not just the amount of precipitation.

__________________

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation and National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Data management support for preparing, documenting, and distributing model driver and output data was performed by the Modeling and Synthesis, Thematic Data Center at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, with funding through NASA.