Written by Nico Kueter, Postdoctoral Fellow

Most researchers experience working in a laboratory that has come into age at some point in their career.

In these labs, you are surrounded by machines and apparatuses whose best days clearly lay behind them. Being fully unaware of the stories they hold, you may even consider discarding some of the old stuff to make room for new furnaces, desiccators, and vacuum pumps. When deciding what stays and what goes, science history sometimes reveals itself unexpectedly.

This is occasionally my job in the stable isotope lab of recently retired staff scientist Doug Rumble.

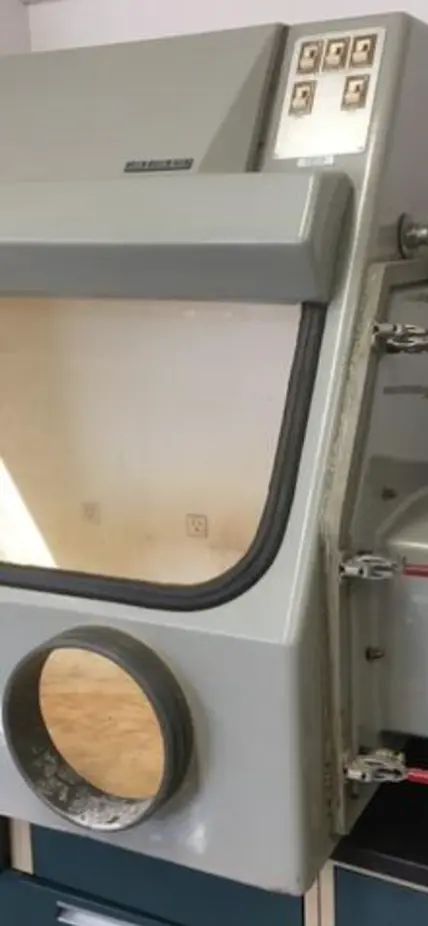

I contacted Doug concerning a bulky glove box occupying a significant proportion of valuable lab space. The glove box is old, has rusty tube- and vacuum connections, and nasty stains of chemical spillage in its interior. Overall, and with no feeling of any sentimentality for this relict, I concluded that this glove box has done its job, and its time has come. So, I contacted Doug asking if the removal was ok, and whether there are hazardous traces of chemicals to be expected—it’s an oxygen isotope lab, after all.

This was Doug’s reply:

“Certainly, move the old glove box wherever you like.

But please remember its history: That box was handed down to me by Peter Bell. Peter used it to store the first Apollo samples. Peter brought Apollo samples back from Houston in a case handcuffed to his wrist in late 1969 or early 1970. The FBI had to come out to the lab and wire his office with a security alarm system.

We set up every table that was moveable in the hallway outside Peter’s door, moved every available microscope onto the tables, and started looking at lunar thin-sections and polished thin-sections.

Everybody was there. Steve Haggerty started screaming a South African war cry when he recognized “armalcolite” as a unique Fe-Ti-oxide species based on reflected light optics with his incredibly calibrated eyeballs. It was a very exciting time! “

Doug further added:

“The discovery story should be more widely known […]. And please be assured that the discovery of Armalcolite by Steve Haggerty is true. I can still remember his shouting and screaming. Steve was transfigured by an ecstasy of discovery.”

The unique Fe-Ti-oxide, ((Mg, Fe2+)Ti2O5, to be exact) found in the moon rocks that were stored in this glove box was later described by Haggerty and coworkers in an international effort involving researchers from the Geophysical Laboratory (now the Earth and Planets Laboratory), University of Chicago, NASA Ames Research Center in California, University of Wisconsin, USGS in Washington D.C., the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, and the Max Plank Institute in Heidelberg, Germany; Published in a Science article from the Apollo 11 Lunar Science Conference.

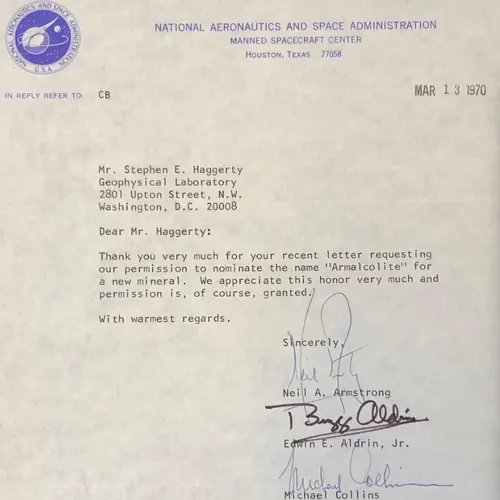

Its name Armalcolite was given in honor of Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins, who collected and returned these very first, precious samples from the moon.

The Astronaut's reply to Stephen E. Haggerty’s request to name the newly found mineral Armalcolite, to honor their endeavors on this extraordinary journey to the moon. Photo credit: Carnegie Institution for Science, Geophysical Lab Archive.

I found a place to tuck the glove box in the lab across the hall.

Science is always looking forward. This story was enough to postpone dumping the glove box for another month or two, but its time had indeed come. Even with this lunar history, the box still had to be discarded to make room for new instruments and future discoveries.

Gladly, I wasn’t the one who had to make that decision.

Katherine Cain and Shaun Hardy are thanked for their contribution to this story.

Literature:

Anderson, A. T., Boyd, F. R., Bunch, T. E., Cameron, E. N., El Goresy, A., Finger, L. W., ... & Ramdohr, P. (1970). Armalcolite: A new mineral from the Apollo 11 samples. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta Supplement, 1, 55.

Photos:

Geophysical Laboratory Image Archive