“Gentlemen, your work now begins, your aims are high, you seek to expand known forces, to discover and utilize unknown forces for the benefit of man. Than this there can scarcely be a greater work. I wish you abundant success…”

These were the words of Andrew Carnegie as he presented his deed of gift to the inaugural Board of Trustees, founding Carnegie Science with the mission to “encourage investigation, research, and discovery” for the improvement of humankind. At 2:30pm on January 29, 1902 a bold new research institution was born.

The Gospel of Wealth

In 1900 Carnegie published The Gospel of Wealth, declaring that the affluent should use their fortunes to advance the greater good. He concluded, “The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.”

The following year, Carnegie sold his steel company to J.P. Morgan for $480 million, making him the wealthiest man in the world. He retired from business and set about putting his philanthropic philosophy into action.

A Donor’s Vision

With a large donation in mind, Carnegie initially considered funding a national university in Washington, D.C., fulfilling a vision that George Washington had proposed a century earlier. But recognizing that such an institution might be seen as competing with existing American universities, he instead conceived of a new and far more exciting plan: an independent research institution dedicated to discovery and investigation for the sake of increasing knowledge. Carnegie saw this as an opportunity to help the United States catch up to the scientific institutions of Europe, writing in a letter, “I read last night an interesting article…which sums up our National Poverty in Science…To change our position among the Nations in the Aim I have in view—We should succeed.”

With assistance from advisors who would later play pivotal roles at Carnegie Science—including Daniel Coit Gilman, the recently retired president of Johns Hopkins University, John Shaw Billings, a physician and head of the New York Public Library, and Charles D. Walcott, director of the U.S. Geological Survey—Carnegie drafted a plan. In mid-December 1901, he announced a $10 million donation in United States Steel Corporation bonds to fund the new research endeavor. It was initially called the Carnegie Institution and went by the Carnegie Institution of Washington between 1904 and 2007, when Science was officially added to the name.

By the end of the month, plans were already underway. Carnegie wrote in a letter on December 20, 1901 “Very busy just now planning the new body which is to control the Ten Million Dollars which I am giving here to be used for securing the exceptional man for the work which he is intended, and supplying the necessary apparatus for experiments and research. We aim to find the geniuses of the Republic and set them to work on the higher problems.”

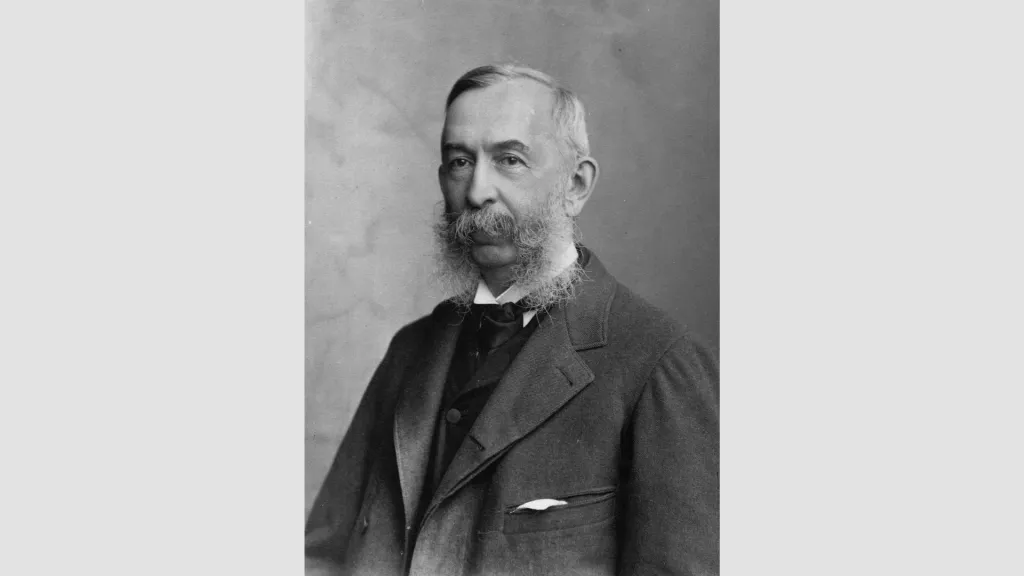

Daniel Coit Gilman, President of Carnegie Science 1902-1904. Gilman, the recently retired president of Johns Hopkins University, advised Andrew Carnegie as he drew up plans for Carnegie Science. Gilman served as the first president of the institution and a member of the first executive committee. He was a cautious leader who preferred to “make haste slowly.”

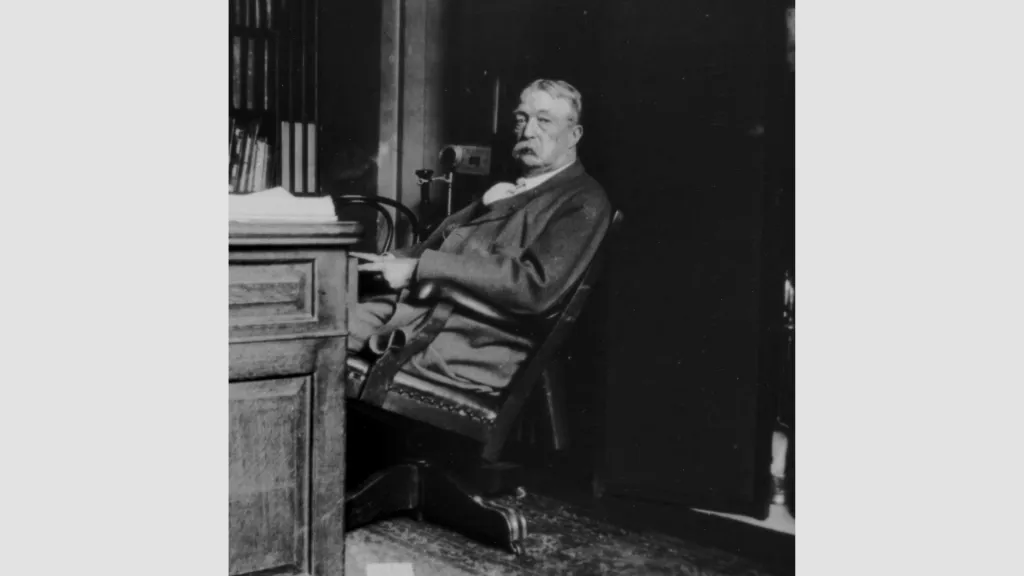

John Shaw Billings seated at a desk, 1913. A surgeon and librarian, Billings was the founder of the National Library of Medicine and director of the New York Public Library. Billings lobbied forcefully for Andrew Carnegie to establish a research institution instead of a university and advocated for supporting exceptional individuals. Billings was a member of Carnegie Science’s first executive committee and quickly became chair of the Board of Trustees. Together with Walcott, Billings essentially ran the institution during its early years. Credit: New York Public Library

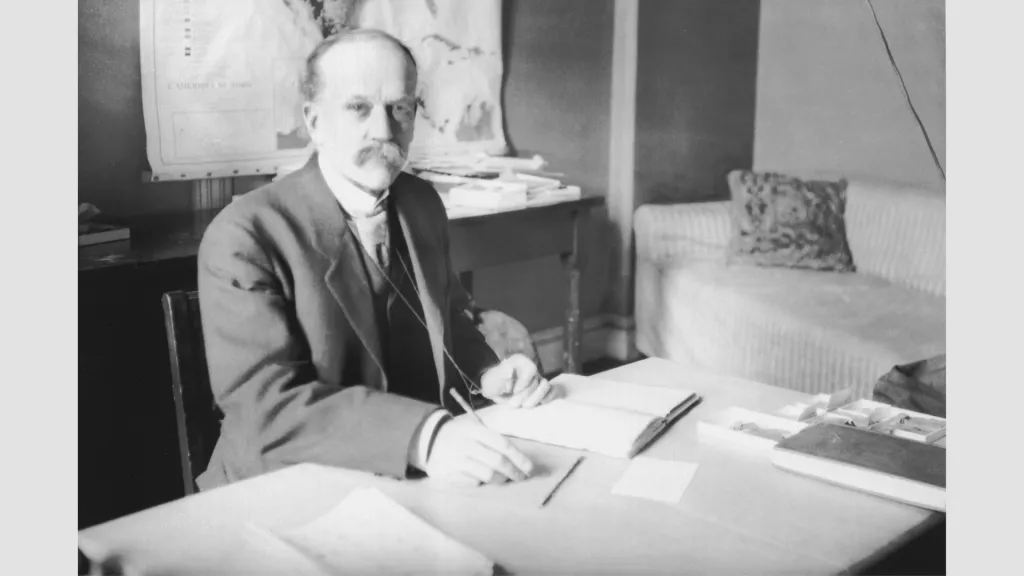

Charles Doolittle Walcott seated at a desk, early 1900s. A paleontologist without formal college or university training, Walcott was the director of the U.S. Geological Survey when he served as an advisor to Andrew Carnegie during the planning for Carnegie Science. He became the first secretary of the institution and a member of the first executive committee. Together with Billings, Walcott essentially ran Carnegie Science during its early years. He went on to serve as the secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and president of the National Academy of Sciences. Credit: Smithsonian Institution Archives

Daniel Coit Gilman

John Shaw Billings

Charles Doolittle Walcott

An Institution for Original Research

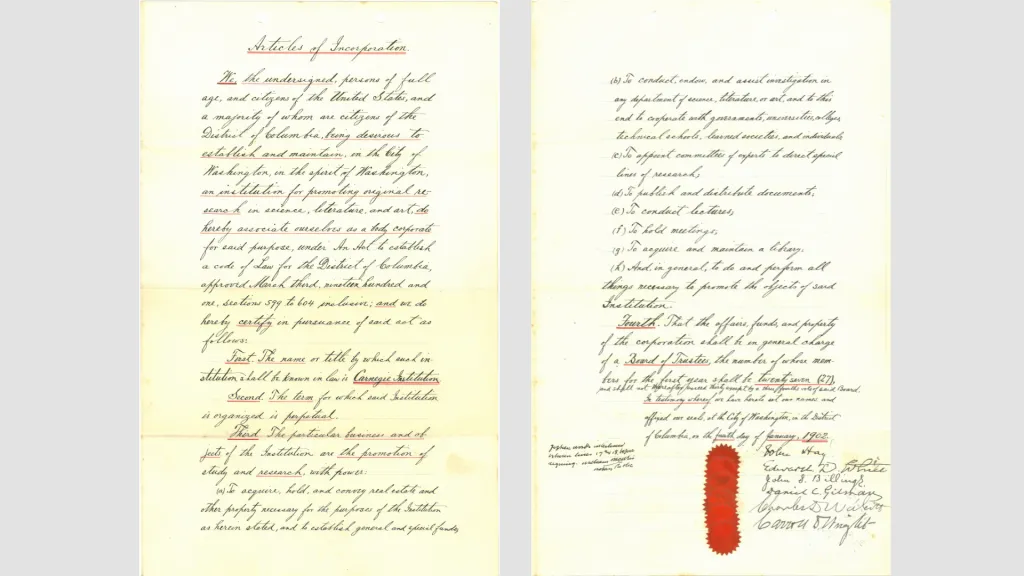

On January 4, 1902, the institution’s articles of incorporation were filed with the District of Columbia recorder of deeds. Twenty-seven distinguished trustees were selected to oversee the fledgling organization. To Carnegie’s pleasure, President Theodore Roosevelt agreed to serve as an ex-officio trustee.

On January 29, 1902, Carnegie and the trustees gathered at the Department of State for the first meeting of the board. Carnegie presented his deed of gift. The first of the aims he laid out was to “promote original research.” Gilman was elected president of the new institution and Walcott secretary. Billings was named the vice chairman of the board. The next day an executive committee including all three men was established, setting the stage for the work to begin.

The first meeting of Board of Trustees where Andrew Carnegie (seated, far right) presented his deed of gift, founding Carnegie Science with the mission to “encourage investigation, research, and discovery” for the improvement of humankind.

Carnegie Science’s original articles of incorporation, which were filed with the District of Columbia recorder of deeds on January 4, 1902. The official name on this seminal document–Carnegie Institution—would be changed to Carnegie Institution of Washington two years later when the organization was reincorporated with a “national charter” by an act of Congress. In 2007, Science was officially added to the name.

First Meeting of the Board of Trustees

1902 Articles of Incorporation

A New Undertaking

The research community buzzed with excitement. The $10 million endowment was enormous, equal to Harvard University’s, and vastly more than what all American universities spent on basic research combined. Opinions abounded about how the money should be spent. The editor of Science, James McKeen Cattell, invited readers to comment on the new research endowment and 44 individuals joined the discussion, offering suggestions of how Carnegie Science might best advance research. By December of the following year, 1,042 applications for funding in 33 fields had poured into the institution.

Although Carnegie’s deed of gift outlined sweeping aims, it provided few specifics about how these goals should be achieved. Faced with a flood of funding requests, the trustees had to carefully consider where and how to direct the institution’s resources.

The executive committee set aside the eight months before the next board meeting to systematically review the current state of research and identify areas of opportunity. As Gilman put it, no major decisions would be made until the trustees had gained insight into “what is now going forward in every department of science in any part of the country.” They commissioned a biographical directory of American scientists and a list of existing research endowments in the United States. Seeking expert guidance, they established 18 advisory committees of specialists tasked with drafting reports on their disciplines: botany, economics, physics, geology, geophysics, geography, meteorology, chemistry, astronomy, paleontology, zoology, physiology, anthropology, bibliography, engineering, psychology, history, and mathematics. These reports, published in the first annual Carnegie Science Year Book, would guide the institution’s funding priorities. Eight members of the advisory committees would see their own dream projects funded by the institution. The balance of disciplines represented by the committees show the foundational preference for science, though initially some funding would also be provided for projects in the humanities, including in history, economics, sociology, anthropology, and archaeology.

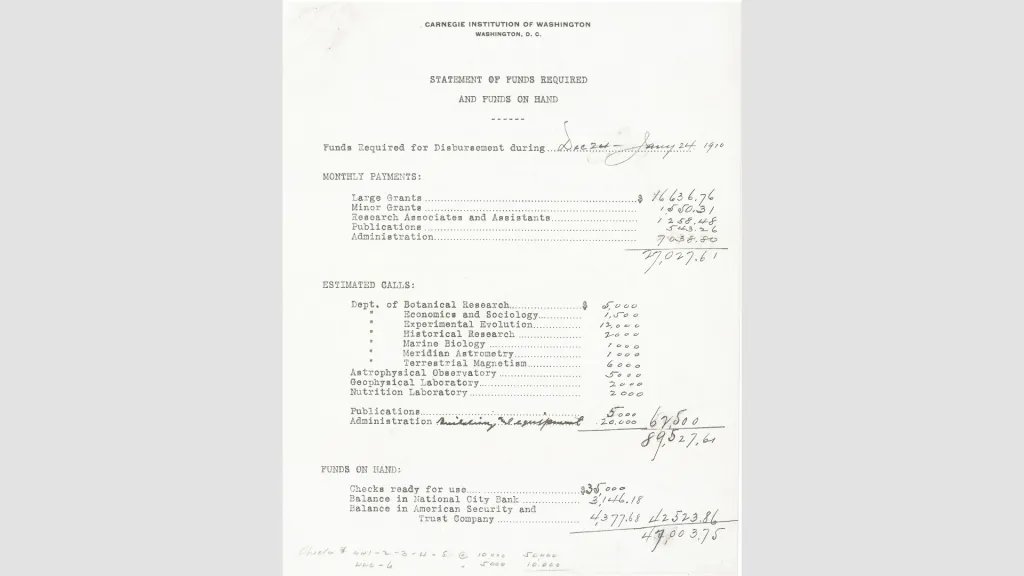

In addition to deciding which fields to support, the trustees had to determine how to provide that support. From the beginning, the institution employed two primary approaches to advancing research: supporting "exceptional” individual researchers through assistantships or individual grants, and funding the institution’s own laboratories or departments with in-house researchers. Over time, and particularly under the guidance of the institution’s second president, Robert S. Woodward, who helmed the organization from 1904-1920, the focus would be placed increasingly on developing laboratories and departments, where teams of investigators tackled the big scientific questions of their day. As historians Nathan and Ida Reingold put it, “The institution was not to be merely a ‘disbursing agency’ but a real participant in research.”

Statement of Funds Required and Funds on Hand, 1910. Originally, Carnegie Science employed two primary approaches to advancing research: supporting "exceptional” individual researchers through assistantships or individual grants and funding the institution’s own laboratories or departments. Over time, the focus would be placed increasingly on developing in-house laboratories and departments.

The staff of the Desert Botanical Laboratory with President Woodward (seated, third from the left) and visitors, 1906. Robert S. Woodward, a mathematician and former dean of pure science at Columbia University, served as the second president of Carnegie Science from 1904-1920. The “first modern manager of science” Woodward had the biggest influence on the development of Carnegie Science and influenced the institution’s focus on in-house laboratories and departments. Credit: Arizona Historical Society

1910 Statement of Funds

Woodward at the Desert Botanical Lab

10 Years In

By the end of its first decade, the institution had established 10 research departments, including the Desert Botanical Laboratory (established 1903), the Department of Terrestrial Magnetism (established 1904), the Geophysical Laboratory (established 1905), and Mount Wilson Observatory (established 1904). These departments, along with the Department of Embryology (established 1914), were the forerunners of Carnegie Science’s current research divisions, where investigators continue to explore key questions about life, planets, and the universe.

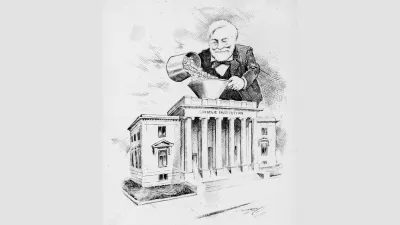

A Division of Publications was organized to disseminate Carnegie Science's extensive research findings through monographs and the annual Year Book. After a visit to Mount Wilson Observatory in 1910, Andrew Carnegie gave the institution another $10 million, doubling its initial endowment. Carnegie Science was well on its way to becoming a leader in research and discovery that would reshape the landscape of scientific inquiry.

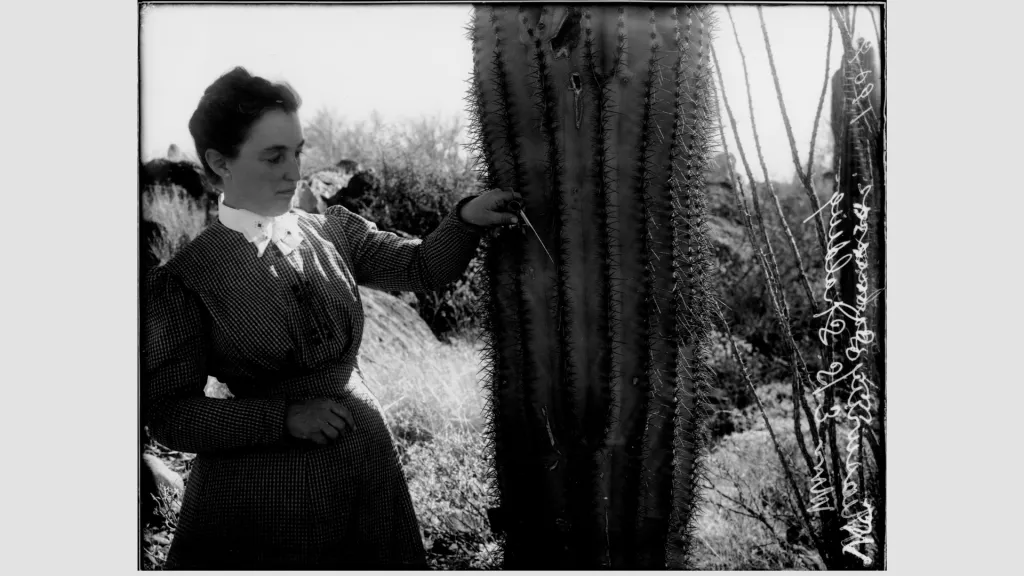

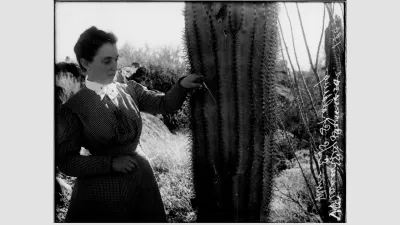

Effie Southworth Spaulding measures a saguaro cactus near the Desert Botanical Laboratory, circa 1909. One of 10 research departments established during Carnegie Science’s first decade, the Desert Botanical Laboratory was devoted to the study of desert plants and how they tolerate, adapt to, and interact with their environment. Credit: Arizona Historical Society

Director Arthur L. Day and a colleague using a carbon arc and resistance furnace at the Geophysical Laboratory, circa 1906. One of 10 research departments established during Carnegie Science’s first decade, the Geophysical Laboratory pioneered experimental studies of rock and mineral formation and the Earth’s interior.

The non-magnetic research vessel Carnegie under sail, 1928. The Department of Terrestrial Magnetism (DTM) was one of 10 research departments established during Carnegie Science’s first decade. Starting in 1905, DTM researchers fanned out across the globe on more than 200 overland expeditions and 10 ocean cruises to map the geomagnetic field of the entire Earth.

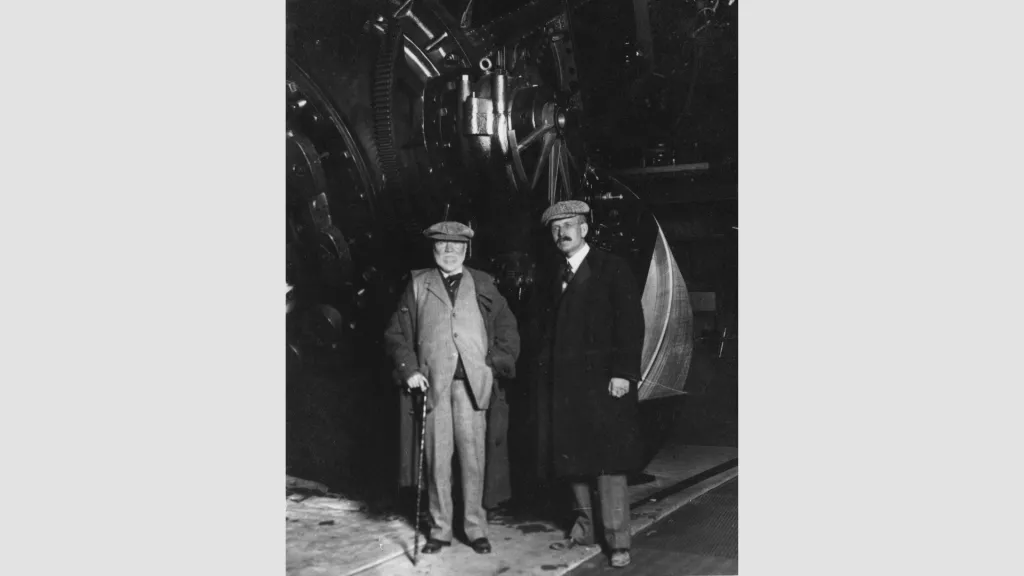

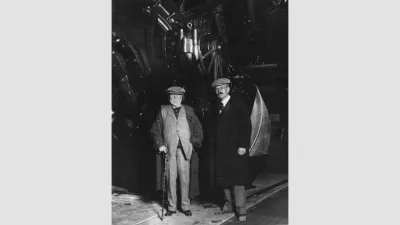

Andrew Carnegie and George Ellery Hale stand in front of the 60-inch telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory. The observatory was one of 10 research departments established during Carnegie Science’s first decade.

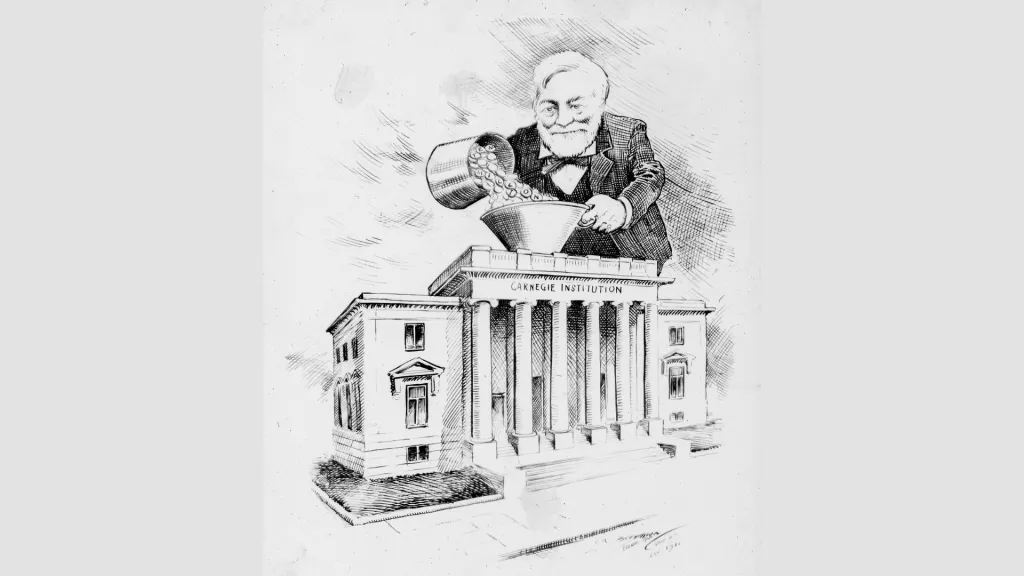

Andrew Carnegie filling the coffers of Carnegie Science, by cartoonist Clifford Berryman, published in the Washington Evening Star, January 1911. After a visit to Mount Wilson Observatory in 1910, Andrew Carnegie gave the institution another $10 million, doubling its initial endowment.

Desert Botanical Lab

Geophysical Laboratory

Carnegie Ship Under Sail

Carnegie at Mount Wilson

Andrew Carnegie filling the coffers

Bibliography

Carnegie, Andrew. Gospel of Wealth and Other Timely Essays. New York: The Century Co, 1901.

Carnegie Institution of Washington. Year Book 1. Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1902.

Kohler, Robert E. Partners in Science: Foundations and Natural Scientists, 1900-1945. University of Chicago Press: 1991.

Miller, Howard Smith. Dollars for Research: Science and its Patrons in Nineteenth-century America. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1970.

Reingold, Nathan and Ida H. Reingold (eds). Science in America, A Documentary History, 1900-1939. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981.

Reingold, Nathan. "National Science Policy in a Private Foundation: The Carnegie Institution of Washington,' in The Organization of Knowledge in Modern America, edited by Alexandra Oleson and John Voss. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979.

Trefil, James and Margaret Hindle Hazen. Good Seeing: A Century of Science at the Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1902- 2002. Washington, DC: Joseph Henry Press, 2002.

Yochelson, Ellis L. “Andrew Carnegie and Charles Doolittle Walcott: The Origin and Early Years of the Carnegie Institution of Washington.” In The Earth, the Heavens and the Carnegie Institution of Washington, edited by Gregory A. Good. Washington, DC: American Geophysical Union, 1994.