Washington, DC—JWST has captured the first-ever evidence of a compound in the atmosphere of an exoplanet—sulfur dioxide—created by a starlight-mediated chemical reaction. The discovery was announced by the mission’s Exoplanet Community Early Release Science Team, which includes five Carnegie astronomers—Munazza Alam, Anjali Piette, Nicole Wallack, Peter Gao, and Johanna Teske—and published, along with other observations of the hot, gas giant planet WASP-39b, in a suite of papers that made the cover of Nature.

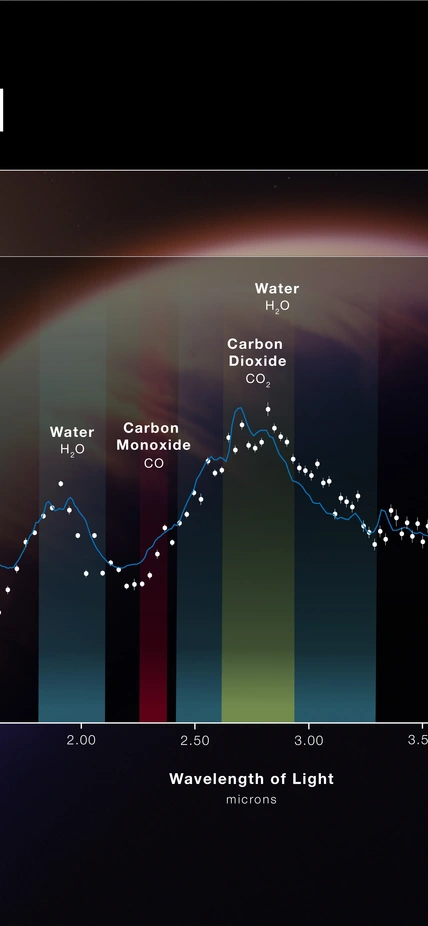

Earlier this year, the same science team announced indisputable observations of atmospheric carbon dioxide around the same exoplanet. As they expanded their analysis of the results, they found a panoply of atoms and molecules in the planet’s atmosphere, including sodium, potassium, water, and carbon monoxide.

“In our previous paper, we saw a mysterious spectral feature in WASP-39b’s atmosphere, which provoked thrilling discussions between team members as we tossed around ideas and investigated the possibilities in real time,” Gao said.

The researchers took the raw data of the planet passing in front of its host star from JWST, and carefully processed and analyzed it to produce a light curve that shows the dip in brightness of the star as the exoplanet transits.

“Analyzing this transit information shows us wiggles and bumps in the planet’s spectrum that represent the makeup of its atmosphere,” Alam explained. “Like fingerprints, each feature indicates the presence of a specific atom or molecule, but the differences in transit depth that we are looking for at different wavelengths are very minute, so our work has to be extraordinarily careful.”

Added Wallack: “The quality of the data is truly remarkable; I was taken aback the first time I saw the raw light curves. Being a part of the Early Release Science program was an incredible experience where I truly felt how excited the whole community is for all we will uncover with JWST.”

Sulfur dioxide was not a compound that the team expected to find in WASP-39b based on their understanding of how the exoplanet’s temperature and pressure conditions would shape the chemical makeup of its atmosphere.

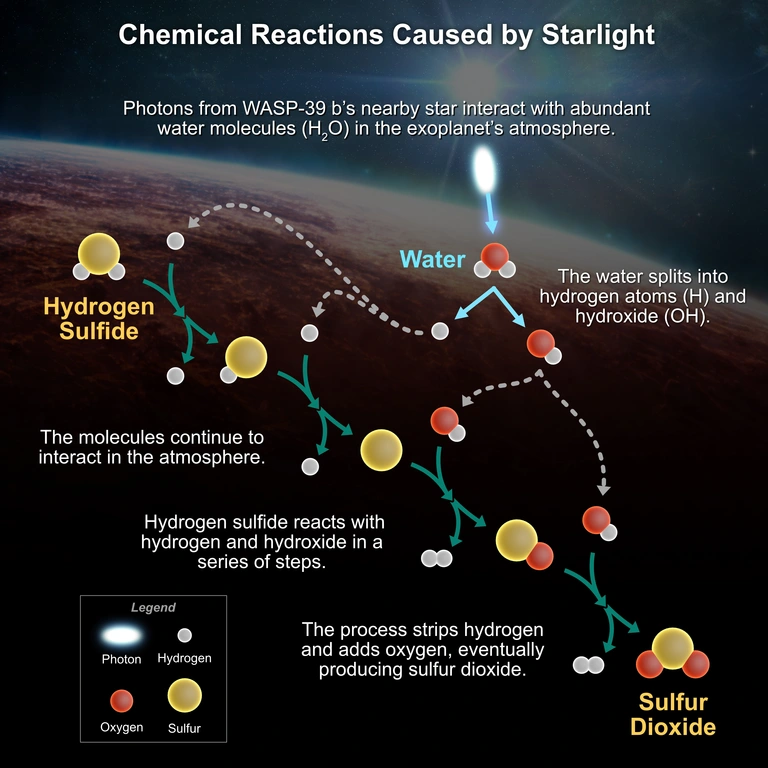

It is created when a different sulfur-containing compound, hydrogen sulfide, interacts with high-energy ultraviolet light particles and hydrogen atoms, initiating a series of chemical reactions that end in its formation.

Photochemistry like this is common in our own Solar System and crucial to the atmospheric makeup of Earth—producing our ozone layers—and that of other rocky planets. It is also fundamental to life on Earth—playing key roles in the photosynthetic process by which plants convert the Sun’s energy to sugars and make our atmosphere oxygen rich, as well as in the production of Vitamin D in our skin.

Discovering light-mediated reactions shaping an exoplanet’s atmosphere provides an important link between the Solar System and the distant worlds, an exciting development when so much planetary science research emphasizes the differences rather than similarities between such systems.

Also of particular interest is WASP-39b’s proximity to its host star–eight times closer than Mercury is to our Sun–which makes it a laboratory for studying the effects of radiation from host stars on exoplanets.

“Planets are sculpted and transformed by orbiting within the radiation bath of the host star," added Natalie Batalha of the University of California at Santa Cruz, who leads the team of researchers using JWST to study transiting exoplanets. “On Earth, those transformations allow life to thrive.”

Better knowledge of the star-planet connection should bring a deeper understanding of how these processes affect the diversity of planets observed in the galaxy.

The authors say that this finding and other species detected in WASP-39b’s atmosphere could also assist future research on the planet-formation process and the ongoing search for forming planets around young stars in rotating disks of gas and dust.

“JWST’s instruments are giving us access to new diagnostics that we can use to connect fully-formed planets back to the compositions of stars and young disks,” Teske concluded. “These connections will help to tease out different formation channels and ultimately the degree to which planet formation varies across the Milky Way galaxy—a core research question for many scientists at Carnegie’s Earth and Planets Laboratory.”