In 1983, at the age of 81, Barbara McClintock received the news that would cement her place in scientific history. She had won a solo Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her discovery of transposons—popularly known as "jumping genes." After the announcement she reflected on her remarkable career: "It might seem unfair to reward a person for having so much pleasure over the years, asking the maize plant to solve specific problems and then watching its responses.”

McClintock's groundbreaking discovery that genes could move within a chromosome revolutionized our understanding of heredity. Although it took two decades for the world to catch up with her remarkable work and recognize McClintock's contributions with the scientific community's most prestigious scientific award, her own confidence in her research never wavered. She remarked "If you know you are on the right track, if you have this inner knowledge, then nobody can turn you off... no matter what they say.”

Crucially, Carnegie Science's commitment to providing leading investigators with the resources to follow their curiosity and define new fields of research provided McClintock the freedom to keep asking maize the questions that enabled her to unlock important genetic mysteries.

Early Brilliance and the Golden Age of Maize Genetics at Cornell

Barbara McClintock was born in 1902, just two years after the rediscovery of Gregor Mendel's work on inheritance. She was raised in Brooklyn and enrolled at Cornell University's College of Agriculture in 1919. During her undergraduate years, McClintock took her first course in genetics, sparking a lifelong passion. She devoted her graduate and Ph.D. studies to the cytogenetics—the study of chromosomes and their role in inheritance—of maize, or corn, a plant she would work with for her entire career.

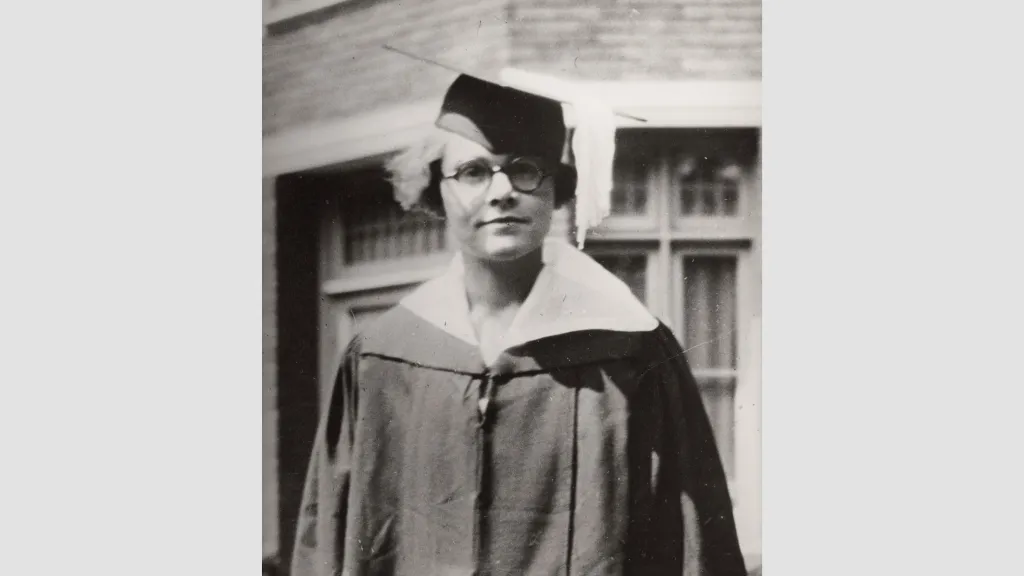

After completing her Ph.D. in botany in 1927, McClintock remained at Cornell as an Instructor and quickly established herself as an unparalleled talent. Within just two years of finishing her degree, she had published six articles, four of them single-authored, and most in top-tier journals. Between 1928 and 1931, Cornell became a hub for maize genetics with a talented group of young researchers supported by R.A. Emerson.

McClintock was a central figure in this golden age of maize genetics and made a series of pioneering contributions. She devised a technique to visualize maize chromosomes and showed for the first time the morphology of the ten maize chromosomes. In 1931, McClintock and collaborator Harriet Creighton published a landmark paper confirming the genetic phenomenon of crossing-over—the mechanism by which X and Y chromosomes exchange genetic information during the formation of egg and sperms cells.

As McClintock’s most recent biographer Lee B. Kass notes, during this period her reputation as "the cytology expert who could see what others could not see" was firmly established.

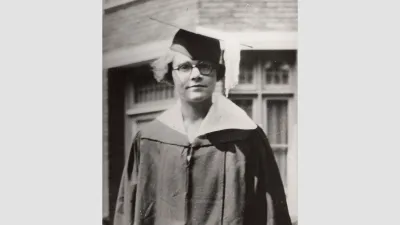

Barbara McClintock in academic regalia in the 1920s. McClintock received her B.A. from the Cornell University College of Agriculture in 1923 and her Ph.D. from Cornell University in 1927. Credit: Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

Barbara McClintock (far right) with Professor R.A. Emerson and other maize researchers at Cornell University, 1929. Between 1928 and 1931, Cornell became a hub for maize genetics with a talented group of young researchers supported by Emerson. McClintock was a central figure in this golden age of maize genetics and made a series of pioneering contributions. Standing from left to right: Charles Burnham, Marcus Rhoades, R.A. Emerson, Barbara McClintock. Kneeling: George Beadle. Credit: Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

Barbara McClintock in academic regalia in the 1920s

Barbara McClintock with Professor R.A. Emerson and other maize researchers at Cornell University, 1929

The Search for Freedom

Despite her extraordinary abilities and reputation, McClintock struggled to find permanent employment that matched her talents. The Great Depression limited opportunities, and she sustained herself in the early 1930s through fellowships, continuing her research at Cornell, Caltech, and the University of Missouri.

One prestigious fellowship with the National Research Council afforded McClintock the freedom to pursue her relentless dedication to maize research. She described the position as allowing her to work when and where she wanted without teaching obligations, including spending the night in the lab if she felt like it. This role enabled researchers “to do what you wanted and really have a wonderful time doing it,” she enthused at the time.

In 1936, McClintock accepted an assistant professorship at the University of Missouri, but very quickly realized it was not the right position for her. The academic responsibilities of teaching, committee work, and administrative duties restricted her research time. In later interviews, she would recall feeling restricted by the bureaucracy at Missouri, where deans and department chairs determined graduate students’ thesis committees and research projects, and permits were required to work in the lab past 10:00 p.m.

McClintock also felt unwelcome as a woman in academia, and worried that her position was not “too secure.” A potential graduate student later recalled McClintock advising her that "women in science were not considered for university jobs” and sharing that “the Missouri Department of Botany really did not want her, and she felt she did not belong."

McClintock was an exceptional scientist of immense intellectual stature and unparalleled technical skill. In the early 1940s her talents would be recognized with her election to the National Academy of Sciences—only the third woman to be elected, and at the young age of 41—election as the first female president of the Genetic Society of America, and election to the American Philosophical Society. Yet in her professional position at the University of Missouri, she felt restricted, unwanted, and insecure. McClintock determined to leave Missouri and find a new institution.

Finding Home at Carnegie

In 1941, McClintock was invited to spend the summer at Carnegie Science’s Department of Genetics at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on Long Island. By the following spring, she had secured a permanent position as a Carnegie staff member, a moment that one of her new colleagues celebrated by exclaiming: "We should mark today's date with red letters in the Department calendar!"

It was a perfect match: a scientist who craved independence found an institution dedicated to supporting unfettered research.

McClintock would remain with Carnegie at Cold Spring Harbor until her death in 1992 at age 90, staying on past her 1967 retirement as a Distinguished Service Member. Overall, this remarkable scientist devoted 50 years to the institution that gave her the freedom and sustained support to pursue her groundbreaking work.

Barbara McClintock in her laboratory at Carnegie’s Department of Genetics at Cold Spring Harbor in 1947. McClintock joined Carnegie Science in the early 1940s. It was a perfect match: a scientist who craved independence found an institution dedicated to supporting unfettered research. Credit: Courtesy of the Barbara McClintock Papers, American Philosophical Society.

Barbara McClintock working in her experimental cornfield in 1953. At Carnegie, McClintock could pursue her research without teaching requirements, administrative burdens, or the pressure to conform to what were at-the-time mainstream scientific paradigms. Credit: Courtesy of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Archives.

Barbara McClintock’s cornfields surrounding the Carnegie Main Building. Carnegie Science empowered McClintock to explore the big questions that interested her. Credit: Courtesy of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Archives.

Barbara McClintock in the laboratory in 1947

Barbara McClintock working in her experimental cornfield in 1953

Barbara McClintock’s cornfields

The Freedom to Discover

For McClintock, Carnegie Science offered something invaluable: autonomy. As she wrote in 1954: "My present situation with the Carnegie is unique... I just go at my own pace here with no obligations other than that which my conscience dictates. That seems to fit my personality rather well."

At Carnegie, she could follow her curiosity without teaching requirements, administrative burdens, or the pressure to conform to what were at-the-time mainstream scientific paradigms.

She later reflected: "I think the sense of freedom was more important than any aspiration...the sense of freedom to be able to pursue an extraordinary type of investigation was the more important aspect. No other aspect could compete with it."

Carnegie Science empowered McClintock to explore the big questions that interested her, facilitating the transformational, Nobel Prize-winning discovery in the 1940s of mobile genetic elements.

The Path to Transposons

At Carnegie’s Department of Genetics at Cold Spring Harbor, McClintock got to work in her experimental cornfield and laboratory, crossing different strains of maize and patiently analyzing the results of her experiments through close study of each plant’s kernels and examination of their chromosomes under the microscope.

This careful experimentation and observation led her to identify what she called "controlling elements," now known as transposable elements, transposons, or simply “jumping genes.” These DNA segments are capable of moving from one location to another on a single chromosome, or even relocating to other chromosomes within a cell! This discovery fundamentally challenged the prevailing genetic paradigm at the time, which depicted chromosomes as stable structures with genes fixed in specific locations.

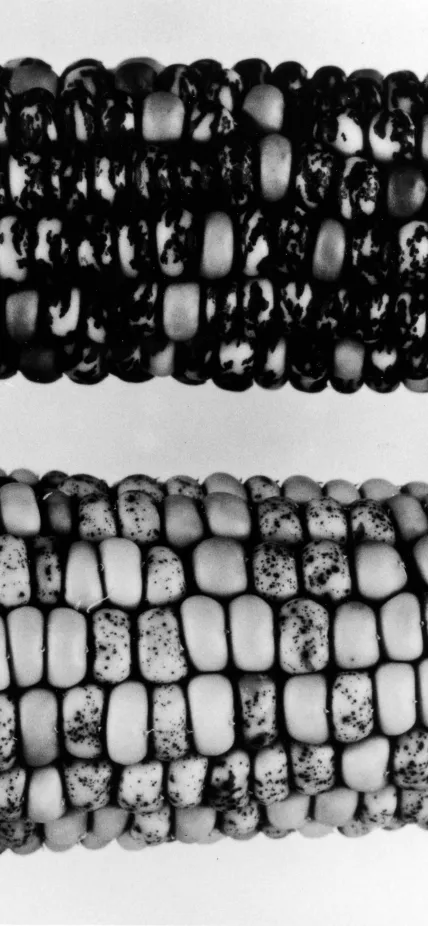

The evidence for transposable elements was visible in the maize kernels themselves, giving each ear a colorful mosaic pattern. And McClintock developed a remarkable ability to "read" the variegated colors and patterns in kernels when chromosomal segments moved into and out of genes.

For example, a maize plant may have an active gene that results in purple kernels. The conventional thinking in the 1930s was that barring a mutation that resulted in white kernels, all subsequent plants grown from those seeds should also produce purple kernels. Because mutations are very rarely reversible, subsequent generations of plants grown from mutant kernels should only produce white kernels.

But McClintock observed that instead of the offspring's kernels being all white, as expected, they displayed patches of purple!

Furthermore, she found that if the initial change in color from purple to white was caused by the insertion of a DNA segment from another section of the genome, which “jumped” into a new position, the color mutation would be reversed more frequently, as the transposon could also “jump” back out of the gene, restoring the original purple color. McClintock deduced that the white parts of the kernel were built from cells containing a transposon, while the purple patches were caused by cells where the transposon had moved out of the gene, restoring its original function and resulting purple color.

For McClintock, the discovery that segments of DNA could move from one location to another on a chromosome, potentially affecting the expression of genes, was “the logical outcome of a series of observations of maize chromosomes, each of which revealed an unanticipated and significant aspect of their behavior.”

The evidence for transposable elements was visible in the maize kernels McClintock studied, giving each ear a colorful mosaic pattern. McClintock developed a remarkable ability to "read" the variegated colors and patterns in kernels when chromosomal segments moved into and out of genes. Credit: Carnegie Science.

Barbara McClintock's labelled maize samples and microscope. For McClintock, the discovery that segments of DNA could move from one location to another on a chromosome, potentially affecting the expression of genes, was “the logical outcome of a series of observations of maize chromosomes, each of which revealed an unanticipated and significant aspect of their behavior.” Credit: Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History.

Barbara McClintock working with maize in her laboratory in 1963. Though her discoveries were underappreciated by her mainstream colleagues, McClintock continued her research undeterred, remarking: “If you know you are on the right track, if you have this inner knowledge, then nobody can turn you off... no matter what they say.” Credit: Carnegie Science.

Maize kernel specimen

Barbara McClintock's labelled maize samples and microscope

Barbara McClintock working with maize in her laboratory in 1963

Ahead of Her Time

McClintock published her findings in 1950 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Science and presented her discovery at the Cold Spring Harbor Symposium the following year. As the Carnegie Science centennial history Good Seeing puts it, “her presentation has entered the scientific folklore as a classic case of a visionary, ahead of her time, being unappreciated by her mainstream colleagues…with the exception of maize geneticists, few people paid much attention.”

Many scientists struggled to grasp the implications of McClintock’s work or dismissed it as a peculiarity unique to maize. The scientific community may not have been ready for the concept of a dynamic genome, and McClintock's emphasis on gene regulation was ahead of its time.

While some recent historians have cautioned against exaggerating the contemporaneous rejection of these discoveries, McClintock herself clearly felt that her findings were not well-received. She later wrote in the introduction to her collected papers, that her 1951 presentation was met with “puzzlement and, in some cases, hostility.” When she only received a handful of reprint requests for a 1953 follow-up article published in Genetics, she “concluded that no amount of published evidence would be effective” to convince the majority of the scientific community to accept her findings.

Undeterred, McClintock continued her research, later remarking “It didn’t bother me, I just knew I was right." She maintained her experimental program and published her findings in Carnegie Science's Year Books.

Vindication and Recognition

It would take more than two decades for the scientific community to fully appreciate the significance of McClintock's discovery. In the late 1960s and 1970s, researchers began finding transposable elements in bacteria, fruit flies, yeast, and mammals, confirming that they were universal features of living organisms.

Acceptance and recognition of McClintock’s trailblazing research spread and honors soon followed. By the early 1980s, McClintock had received an avalanche of prestigious awards, including the Kimber Genetics Award, the National Medal of Science, the Lewis S. Rosenstiel Award for Distinguished Work in Basic Medical Research, the Lewis and Bert Freedman Foundation Award for Research in Biochemistry, the Wolf Prize in Medicine, the Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award, the Thomas Hunt Morgan Medal, the Charles Leopold Mayer Prize, and the Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize.

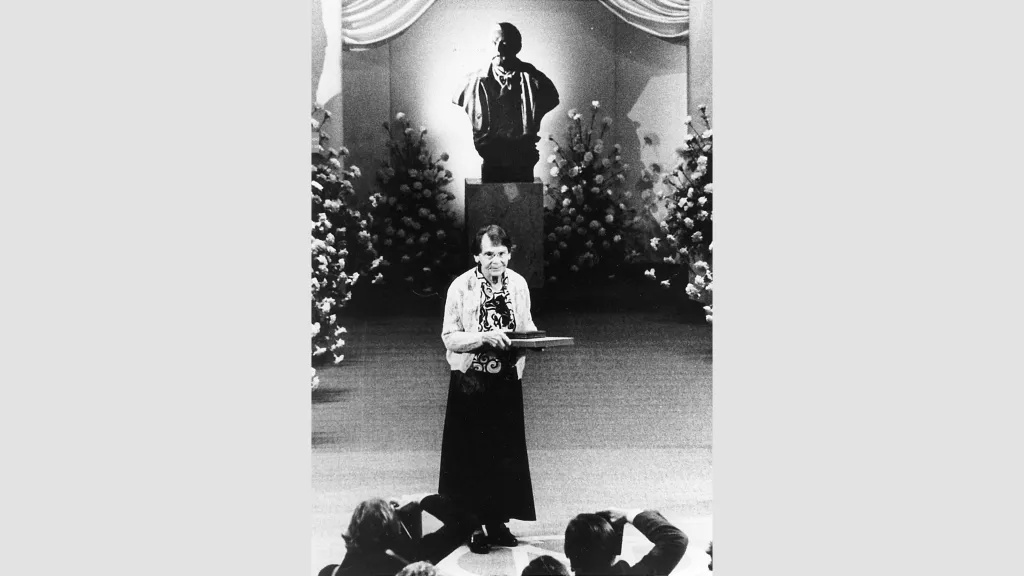

The Nobel Prize in 1983 represented the culmination of this belated acknowledgment. McClintock was only the third woman to receive the honor, and she remains the only woman to win an unshared Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Barbara McClintock (center, blue shirt grey jacket) surrounded by journalists after the announcement that she had won a solo Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her discovery of transposons—popularly known as "jumping genes." Credit: Courtesy of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Archives.

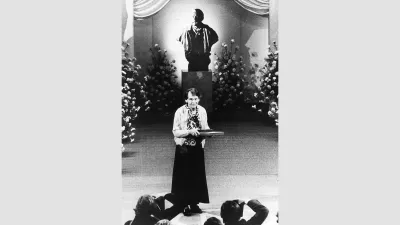

Barbara McClintock at the Nobel Prize Ceremony in 1983. McClintock was only the third woman to receive the honor, and she remains the only woman to win an unshared Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Barbara McClintock (center) with Carnegie President Maxine Singer (left) and Carnegie molecular biologist Nina Fedoroff (right) at a 1989 Carnegie event held in honor of McClintock. Credit: Carnegie Science.

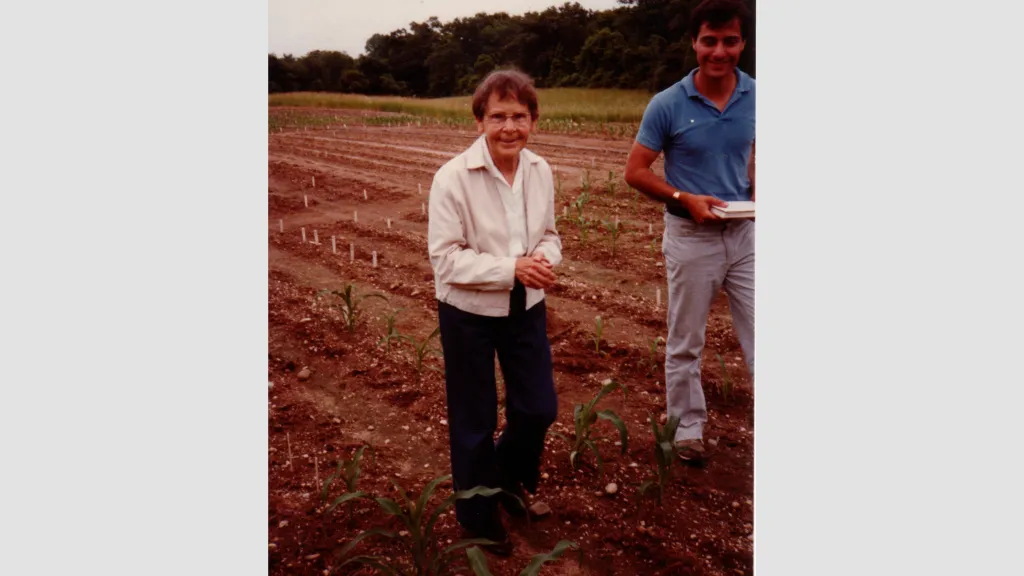

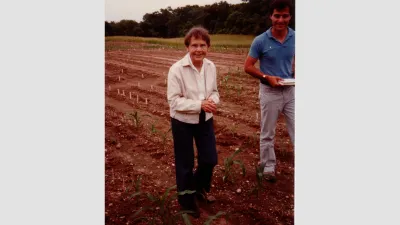

Barbara McClintock standing in a cornfield in 1983. McClintock would remain with Carnegie at Cold Spring Harbor until her death in 1992 at age 90. Overall, this remarkable scientist devoted 50 years to the institution that gave her the freedom and sustained support to pursue her groundbreaking work. Credit: Courtesy of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Archives.

Barbara McClintock (center, blue shirt grey jacket) surrounded by journalists

Barbara McClintock at the Nobel Prize Ceremony, 1983

Barbara McClintock with Carnegie President Maxine Singer and Carnegie molecular biologist Nina Fedoroff

Barbara McClintock standing in a cornfield in 1983

A Scientific Legacy

Former Carnegie Science Staff Scientist Nina Fedoroff, who would provide molecular confirmation of McClintock's work, wrote that McClintock "shook a few shoulders and more than a few minds, engendering the courage to break free and see the unfamiliar with new eyes, rearrange the pieces in novel ways, remaining faithful only to what is really there, not the dogma of the day."

McClintock’ story underscores the importance of institutional support for independent, curiosity-driven research. Carnegie Science provided the environment McClintock needed to pursue her groundbreaking work. She herself noted, "That's what the Carnegie is for, to pick out the best people they can find and give them freedom."

Bibliography

- Comfort, Nathaniel C. The Tangled Field: Barbara McClintock’s Search for the Patterns of Genetic Control. Harvard University Press, 2022.

- Fedoroff, Nina and David Botstein (Eds). The Dynamic Genome Barbara McClintock’s Ideas in the Century of Genetic. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1992.

- Kass, Lee B. From Chromosomes to Mobile Genetic Elements: The Life and Work of Nobel Laureate Barbara McClintock. CRC Press, 2024.

- Keller, Evelyn Fox. A Feeling for the Organism: The Life and Work of Barbara McClintock. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman, 1983.

- McClintock, Barbara. The Discovery and Characterization of Transposable Elements: The Collected Papers of Barbara McClintock. New York: Garland Publishing, 1987.

- Trefil, James and Margaret Hindle Hazen. Good Seeing: A Century of Science at the Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1902- 2002. Washington, D.C.: Joseph Henry Press, 2002.