Washington, DC— A new model that defines the connections between individual level ecological processes and larger aquatic food webs—linking microscopic biology with ecology in greater detail than previously thought possible—could deepen our understanding of the laws of nature and inform ecosystem management efforts.

Developed by researchers from Carnegie and Michigan State University, the model demonstrates that relationships that shape individual plankton physiology and plankton community dynamics—for example, the correlation between an organism’s size and its nutrient consumption—scale up in mathematically predictable ways that affect whole ecosystems. Their results are published in Science.

“We can now show how lower-level rules of life feed into these higher levels based on ecological interactions and evolutionary considerations,” explained Carnegie’s Elena Litchman, whose long-standing collaboration with MSU’s Chris Klausmeier underpinned this project. “Up until now, people had considered these levels in isolation.”

Over the past several decades, scientists have formulated mathematical rules that separately describe important relationships at the microscale and macroscale. However, attempts to bridge the scales have left researchers wanting.

That’s because previous attempts to accomplish this goal have had to make compromises, according to lead author Jonas Wickman, an MSU postdoc. Some earlier models have chosen simplicity at the expense of accuracy and realism. Others have confronted that complexity with brute computational force, making them less accessible and more unwieldy.

“Our model includes actual ecological and evolutionary mechanisms but is simple enough to use,” Wickman said.

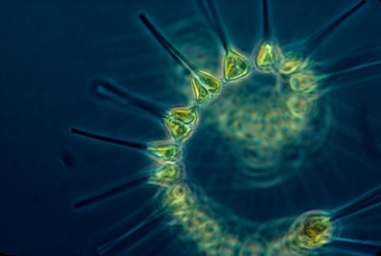

Credit: NOAA MESA Project.

“The revelation that patterns emerging at macroecological scales can be explained by properties of individual organisms at microecological scales is as compelling as it is elegant,” added Steve Dudgeon, program director in the U.S. National Science Foundation’s Directorate for Biological Sciences, which helped fund the work. “The study provides new avenues of research that could enhance prediction of how ecosystems, and the relationships among the organisms in them, will change with eco-evolutionary dynamics interacting in changing environments.”

Focusing on plankton, Litchman and Klausmeier’s joint research effort deploys a combination of fieldwork, lab research, mathematical modeling, and data synthesis to pursue fundamental questions about community ecology and reveal the ways that ecosystem dynamics play out across scales—from the physiological to the global.

“They’re relatively simple organisms, ”Klausmeier said, describing plankton. “If anything is going to follow the rules, plankton are a good candidate. But they’re also globally important. They’re responsible for about half of the primary production on Earth and are the base of most aquatic food webs.”

Primary producers use biochemical processes such as photosynthesis to turn the Earth’s carbon and raw nutrients into compounds that are useful for the organisms themselves, as well as often for their predators or even humans. This means plankton are a critical cog in the natural machinery that cycles the planet’s life-essential elements, including carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen.

Credit: Robert Simmon and Jesse Allen/NASA

This new scaling model that describes plankton can be useful for better understanding those key processes, as well as if and how they are changing with the planet’s climate. The team did not include climate-associated variables like temperature in this study, but they are already planning their next steps in that direction.

Looking ahead, Litchman, Klausmeier, and Wickman will design new experiments to test, refine, and expand their model by extending it to other species and ecosystems. This could ultimately lead to the model being able to inform ecosystem management strategies in various environments around the globe.

“The effects of global warming could alter the lower-level physiological processes,” Litchman said. “We could then use this framework to see how those effects bubble up to different levels of organization.”