Maxine Singer (1931 – 2024)

Join us in honoring Maxine Singer, President Emerita of Carnegie Science, whose pioneering research and advocacy transformed the scientific community.

Carnegie Science's First Female President

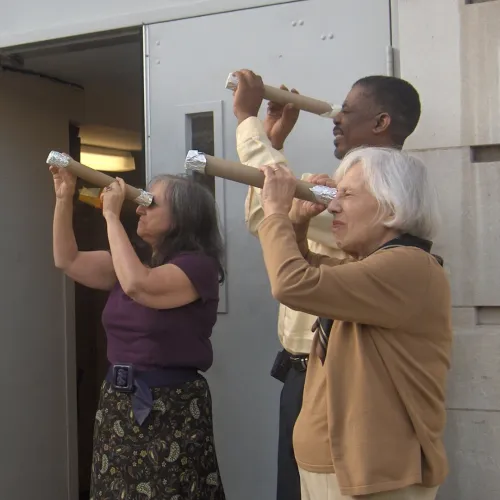

During her fourteen years as President of Carnegie Science, Maxine Frank Singer led the institution into a new era of discovery and impact. As the first woman in the role, she oversaw the construction of the Magellan telescopes at the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile, which have fueled groundbreaking astrophysics research for over 20 years. She also established Carnegie’s first new research department in over 80 years—the Department of Global Ecology—leading the way in studying large-scale environmental challenges.

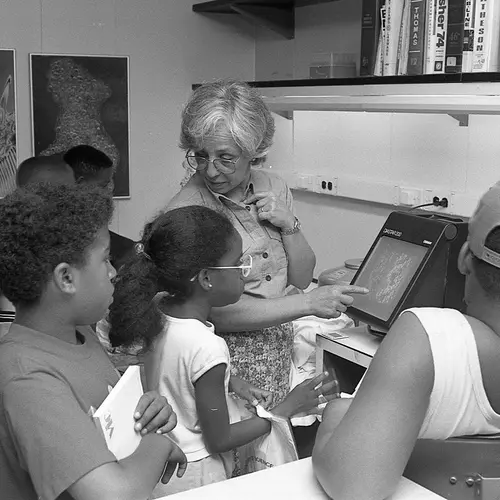

Singer prioritized education and outreach, creating programs such as the Capital Science Evening lecture series and the Carnegie Academy for Science Education. Her vision and leadership not only strengthened Carnegie Science’s research capacities but also expanded its role as a vital institution for both scientific discovery and education.

Leading the Way in Genetic Research

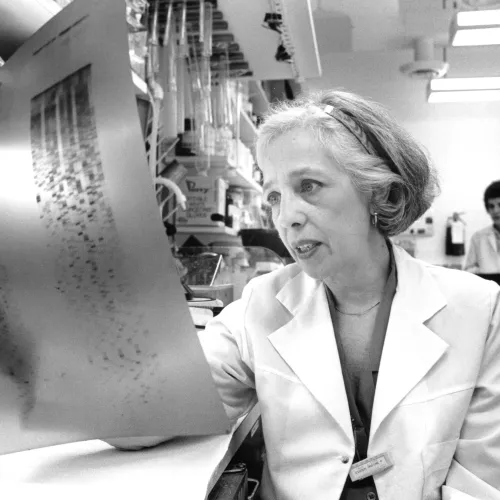

After earning her Ph.D. from Yale, Maxine Singer joined the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 1956—a mere three years after the discovery of the DNA double helix.

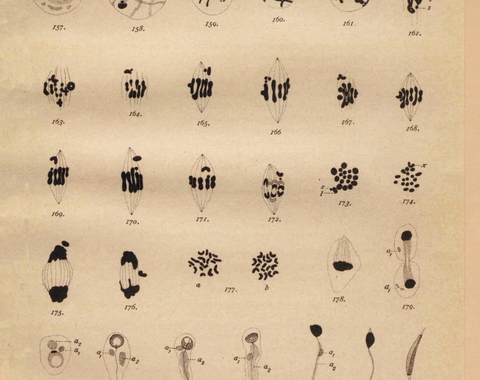

Her early research, which focused on RNA and DNA synthesis, helped lay the foundation for the decoding of the genetic code in the 1960s. One of her most significant scientific contributions was the discovery of the LINE-1 DNA sequence, which can "jump" within the human genome, causing mutations that may lead to genetic diseases. This breakthrough reshaped our understanding of genetic mobility and its role in evolution and disease. Singer’s scientific work contributed to the development of molecular biology as we know it today, and her legacy continues to influence generations of researchers.

Advocacy for Ethics in Genetics

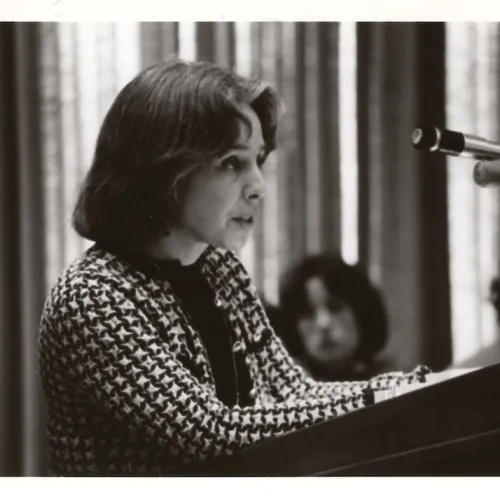

Maxine Singer was a key figure in creating ethical guidelines for genetic research during a time when public concern was growing. In the early 1970s, as recombinant DNA research and gene splicing gained public attention, Singer became a trusted voice for balancing scientific progress with public safety. Seeing the potential risks of unregulated genetic research, she urged caution in a co-authored letter in Science which ultimately led to 1975 Asilomar Conference. As an organizer of this historic gathering, Singer helped guide discussions among the 150 scientists in attendance, leading to the adoption of voluntary guidelines and safeguards for high-risk experiments.

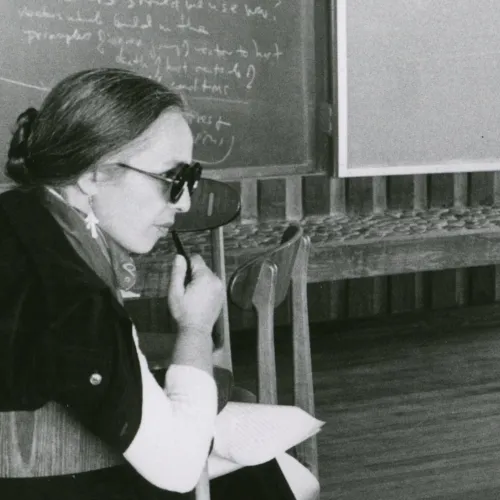

Beyond the lab, she was a dedicated advocate for responsible genetic research. Singer engaged with the public at forums, debated critics, and testified before Congress (pictured), helping to build trust and set lasting standards for scientific responsibility. This experience also strengthened her commitment to science education, which she saw as essential for an informed and engaged society.

Science to the People

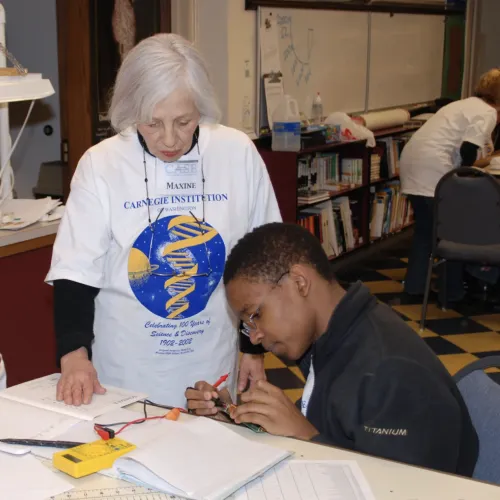

Throughout her career, Maxine Singer was a dedicated advocate for women and minorities in science. As President of Carnegie Science, she launched several educational outreach initiatives aimed at providing hands-on science experiences to students and teachers in Washington, D.C. Notably, she founded the First Light Saturday science school and the Carnegie Academy for Science Education (CASE), which have served thousands of D.C. students and teachers.

Singer continued to work with CASE and other programs, such as Math for America, long after her retirement. Her advocacy work has left a lasting impact on STEM education and inspired future generations of scientists, educators, and policymakers.

Highlighted Works

|

Blossoms And the Genes that Make Themby Maxine Singer | June 5, 2018 |

|

Exploring Genetic Mechanismsby Maxine Singer and Paul Berg | May 7, 1997 |

|

Why Aren't Black Holes Black?by Robert M. Hazen and Maxine Singer | Apr 14, 1997 |

|

Dealing With Genes: The Language of Heredityby Paul Berg and Maxine Singer | Jan 1, 1992 |

|

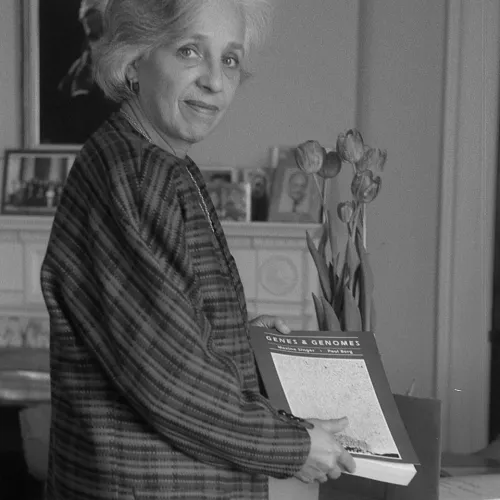

Genes and Genomes: A Changing Perspectiveby Maxine Singer and Paul Berg | Feb 28, 1991 |

Genetics and the Law: A Scientist’s View

Yale Law & Policy Review, 1985

Heroines and Role Models

Science, 1991

Thoughts of a Nonmillenarian

Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 1997

Inspired Choices

Science, 1998

Regulating Human Cloning

Science, 1998

Believing Is Not Understanding

The Washington Post, 1999

Enhancing the Postdoctoral Experience

Issues in Science and Technology, 2000

Shaping the Future for Women in Science

The American Society for Cell Biology Newsletter, 2000

Maxine Singer Speech Repository

Maxine Singer authored 131 papers, including articles, review articles, meeting abstracts, notes, editorial material, and letters. As of November 2024, these papers have been cited 6,487 times.

Top Cited Works:

Highly Repeated Sequences in Mammalian Genomes - 1982

SINEs and LINEs: Highly repeated short and long interspersed sequences in mammalian genomes - 1982

Unit-length line-1 transcripts in human teratocarcinoma cells - 1988

Cytoplasmic ribonucleoprotein complexes containing human LINE-1 protein and RNA - 1996

Summary statement of the Asilomar conference on recombinant DNA molecules - 1975

- 1978: Elected Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- 1988-2002: President of the Carnegie Institution of Washington

- 1990: Elected to the American Philosophical Society

- 1992: Awarded the National Medal of Science for outstanding scientific accomplishments and her commitment to societal responsibility in science

- 1999: First woman to receive the Vannevar Bush Award

- 2007: Awarded the Public Welfare Medal from the National Academy of Sciences

Shared Memories

I met Maxine as a postdoc in Marnie Halpern's lab (then at Carnegie Embryology). It was Maxine's passion for making a difference in the science education of K-12 students that impressed me. So much so that when I was an Assistant Professor, I started BioEYES, a program that uses zebrafish to excite kids about science. When we launched BioEYE in 2002, I asked Maxine to advise our program. Maxine generously shared her wisdom, which is certainly one factor that helped us grow to a program that is all over the world and approaching 200,000 children served.

Maxine told me the following with regard to the state of science education in the US: Image when students were in primary grades, they learned the names of famous baseball players. Then, as they got older, they memorized the rules. In high school, they got to hold a ball and glove or maybe walk on the field. Never did they ever get a chance to play the game. She believed it was essential that every child have a chance to have a hands-on science experience.

Maxine Singer was Carnegie's president when I came to DTM (Department of Terrestrial Magnetism*) as a postdoc and remained so until several years after I was hired onto the scientific staff. She was an absolutely amazing scientist, administrator, and human being.

Despite being my boss's boss and in an utterly different field from me, she was always eager to talk science with me and listen to my ideas about, well, anything. I was lucky enough to live in the same neighborhood as her, so even long after she retired, I would regularly run into her on walks or at the grocery store, and she always wanted to catch up.

She is sorely missed.

*The Department of Terrestrial Magnetism merged with the Geophysical Laboratory to form the Earth and Planets Laboratory in 2020.

I was a Ph.D. student at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Professor Ernest Winocour’s laboratory when Maxine came with her family for a sabbatical. She became my mentor, colleague, guiding light in my academic journey, and a close friend. Over time, our relationship grew so deeply that my family and I came to see Maxine, Dan, and their children as part of our extended family.

My first encounter with Maxine at the Weizmann Institute left a profound and lasting impression on both my scientific and personal life. I vividly recall standing in Ernest’s office as Maxine shared the groundbreaking news of Dan Nathans’ talk at the Gordon Conference, where he described the use of restriction enzymes to study SV40 DNA—heralding the dawn of a new era in molecular biology. I was fascinated and in awe to discover that this brilliant scientist, who would be joining our lab for a year, was accompanied by her husband Dan, a distinguished lawyer, and their four young children. This remarkable balance between her family life and her dedication to groundbreaking scientific research demonstrated that it is possible to excel in both realms simultaneously.

She inspired and mentored me, guiding me through critical professional decisions with wisdom and care. Above all, she treated me as an equal and a trusted friend.

I had the honor of being Maxine's primary care internist for 20 years. Maxine confirmed my career decisions and goals. She made me proud to be a primary care doctor. Her family is exemplary, and her dedication to it is obvious. Knowing that it is entirely possible to be your full professional self AND love and nurture your family is a role model we need for all. Thanks, Maxine!

Maxine was most impassioned about her work in science education. She shared with me her stories about her efforts to expand science education to youth. As a primary care doctor, I share this belief with her and wish we could expand our understanding of human disease at a young age so we all have more comfort and education about our human bodies over the lifespan. Maxine was an easy patient. She understood human biology and was accepting of her changes during her later life. We should all be so accepting!

I had the great privilege of working in Maxine’s lab at the NIH for 2 summers while I was in college. In 1977-78, molecular biology was just beginning to come of age, and Maxine was right at the forefront. I remember that the lab was a hub for many of the stars in the field who came to visit, and it was a very exciting but busy time. Nevertheless, Maxine was always able to make time to talk and troubleshoot with people in the lab. Soon after I arrived in the lab, I had to seed 200 plates of cells on a Friday for an experiment to begin on Monday. When I came into the lab after the weekend, I was crestfallen to discover that the plates were contaminated with yeast. I had had experience with tissue culture and, of course, was incredibly embarrassed, and I couldn’t understand how this had happened.

Rather than throwing this incompetent undergraduate out the door, Maxine sat down with me and said that there must be a logical explanation. After going over my whole day and not finding any red flags, Maxine remembered that I had mentioned to her that I enjoyed baking challah. Sure enough, that Thursday night, I had prepared challah and baked it in the morning. After that, my challah routine changed, and my cultures remained sterile. More importantly, I carry with me the lessons I learned from Maxine about respecting every person and taking the time to learn from even simple, silly mistakes to this day.

Maxine's excitement for science was infectious, and she helped direct me into my career in science, for which I am forever grateful. I remember an interview of Maxine with Bill Moyers in which she said that one of the reasons she went into science was that there are not many careers in the world in which you can say you learned something new every day. That excitement certainly inspired me, and I think all who knew her.

I knew Maxine slightly, and she knew me. She had a close friendship with my director, Leonard Searle, which is the origin of my connection with Maxine. I appreciate the kindness she showed me.

Of course, she was a notable intellect, as was Leonard. It was their friendship that ensured the construction of the Magellan telescopes in Chile; without that, Carnegie Astronomy might have died out. We owe our careers to Maxine and Leonard's friendship and their intellect.

The last time I saw her, she told me of a new book on flowers she had just published. I was amazed at her ability to continue to contribute to Science at the age of 87.

Maxine Singer was my predecessor as the president of the Carnegie Institution. She left a remarkable imprint on Carnegie as a result of her recruitment and encouragement of top-level scientists, her engagement with them, and the initiatives she launched. These included the establishment of the spectacular Singer Building at Johns Hopkins as the home for the Embryology Department, nurturing the continuation of the incredible and productive scientific culture of that group. She also oversaw the construction of the two Magellan telescopes in Chile, keeping the Carnegie Observatories at the cutting edge of astronomy. Additionally, she launched the Department of Global Ecology, enabling scientists from many different disciplines to address climate change without the barriers often imposed by academic silos. These were noteworthy accomplishments on which I was able to build.

Maxine had a commitment to education. She recognized that the District was disadvantaging its children due to the decrepit state of the educational system, particularly in science and math. Because Carnegie was a significant scientific institution in the District, she felt that Carnegie had a responsibility to try to address this need. Throughout her tenure and mine, Carnegie held Saturday morning classes for District children in the P Street building, where various scientific subjects and projects were explored. A large room in the basement was dedicated to this effort and included aquariums, microscopes, and various other materials for the kids to use, as well as full-time staff to nurture the program. This effort launched some kids onto educational trajectories they otherwise might not have followed.

Many of the teachers responsible for science education in the District’s schools had no prior educational experience in science. Maxine launched a program in which District teachers were brought into the building during the summer for a week or two of training on how to teach science. The program provided some focus on substance but also included training on effective classroom instruction. The training featured something that was anathema to the teachers—the videotaping of a participant's efforts to teach a subject, followed by a review of the videotape and a discussion (with gentle criticism) of the teacher's performance. To encourage participation in the workshops, teachers were paid to attend, and they grudgingly accepted the indignity of the videotape. But they learned. One teacher at a final session said to me, "I came to Carnegie to learn how to teach science, but I left having learned how to teach."

The memorial symposium focused on the establishment of a Math for America outpost in Washington. Math for America was the brainchild of Jim Simons, the phenomenally wealthy hedge fund founder and a mathematician himself. The program involved an arrangement with American University to provide both a master’s degree in mathematics and an educational certificate. Carnegie would find appropriate candidates for the program, pay for their education, and provide a stipend, with the commitment that recipients would teach mathematics in the District’s schools for a certain number of years. We even increased their school salary to meet norms for those with a master’s degree and provided mentors to help them navigate the challenges of teaching in some of the District’s schools. At the symposium, we learned that the program has had a lasting and very positive impact on mathematics education in the District.

One amusing anecdote relates to the initial funding for the Math for America DC effort. Maxine went to New York to pitch funding to Jim Simons. She was ushered into his office and noticed an ashtray on his desk. She asked if he minded if she had a cigarette. Simons, incredibly pleased to find someone who shared his addiction, pulled out his own pack of cigarettes. They bonded as a result, and our funding was forthcoming.

I worked with Maxine on the Math for America DC program. She continually pushed to improve the math teaching in DC. Dozens of teachers went through the program, and thousands of students benefitted from their dedicated work in the schools. None of this would have happened without Maxine’s leadership.

I met Maxine at a time when I was considering a move from Michigan State to lead a Max Planck Institute. She convinced me and my wife Shauna, who was also a professor at Michigan State, to move to Carnegie instead. That had a very large impact on our lives.

Maxine appointed me as Director of the Department of Plant Biology in 1993, so I had a lot of interactions with her until she retired as President. I greatly enjoyed interacting with her because we shared a common enthusiasm for science and scientists. I always felt that we had the same goals.

My most impactful interactions with her probably arose when I proposed that we spin out a new Department of Global Ecology. Two of the staff members in Plant Biology, Chris Field and Joe Berry, had got me positively excited about their work on observing ecosystems from space using a database they developed that could interpret what the Earth-orbiting satellites were seeing in 256 wavelengths. And they had also made me very concerned about climate change. Maxine responded by forming a committee to discuss the general question of whether Carnegie should have a new department and, if so, what should the focus be. She convened a series of meetings, leading to an interesting and thoughtful process that ultimately endorsed the idea. I thought she was a wonderful leader.

I can best say that Maxine was my friend. She was the reason that there was a Math for America DC, and I was hired as a mentor for new mathematics teachers after I retired from the University of the Virgin Islands and worked for the Mathematical Association of America. Her interest in the work we did as mentoring was a continuing support. She supported our mentees, too, with her demonstration of interest in the Mathematics history class I taught.

Maxine first came to my attention when I was on the nominating committee for the Sara Lee Corporation Frontrunners Awards. They gave four awards a year to outstanding women in four different fields. Maxine was a nominee. Reviewing her resume, I noticed that she was affiliated with Weizmann Institute in Israel.

At that time, I was Chair of the Board of Weizmann America, and I had also initiated the Weizmann Women and Science Award. I followed up and called her and she soon became the best mentor I could have—and a very special friend. I was told at the time that I needed an outstanding nominating committee to have a viable and prominent award. Whoever I asked to be on the Nominating Committee accepted when they heard Maxine was involved. We ended up with two Nobel prize winners and an outstanding Committee.

I had so much admiration for Maxine...her honesty...her insights...her ability to explain..her wisdom..her intuition...She said what she believed and believed what she said. I could not have had a better friend. She has left a hole in my heart.

Maxine did not waste time chit-chatting and would ask, "How would you do it?"

I first met Maxine at Carnegie Academy for Science Education when I was a scientist volunteer at Janney Elementary School (public) in Washington, DC. It was a surprise for me to learn that the academy and First Light were created by such a prominent scientist. She told me if you do not cultivate the children's natural curiosity, you will lose them very quickly.

Maxine is the optimal role model of an exceptional scientist who also cared about science education of the next generations and acted on it by developing programs and providing conditions for the teachers and students to achieve that. Providing opportunities for students and teachers from less resourceful backgrounds is an important factor in programs I develop.

Forever grateful to Dr. Maxine Singer🇺🇸 who spearheaded the construction of the twin Magellan telescopes at the Carnegie Las Campanas Observatory in #Chile 🇨🇱that have enabled two decades of breakthrough #astrophysics & #astronomic research.@LCOAstro @sochias_cl @womeninstem https://t.co/CtdfRFNfpS

— Belen Sapag M. (@BSapag) July 25, 2024

Obituary: Maxine Singer (1931-2024) biologist who shaped genetic engineering and fought discrimination https://t.co/zGjyNygXkC

— nature (@Nature) August 3, 2024

Our Office was saddened to hear of the recent passing of Dr. Maxine Singer. Alongside Dr. Marshall Nirenberg, Singer was a key player in deciphering the genetic code. She further supported the field by developing guidelines for safe, ethical genetic research with @theNCI. pic.twitter.com/TeVAvakIc6

— NIH History Office (@historyatnih) July 18, 2024

We lost a great leader today - Maxine Singer, advocate for STEM education for all, besides being a pioneering scientist. Be inspired by her 2010 @SocDevBio Viktor Hamburger Outstanding Educator Prize lecture: https://t.co/oJQj2tMBup. https://t.co/XpSbgGBOMR

— Ida Chow (@clawedfeet) July 10, 2024

Maxine was a giant intellect, scientist & humanist. She was President when I was a Staff Associate @CarnegieDevBio

— A. Sánchez Alvarado (@Planaria1) August 4, 2024

On the occasions we spoke, I always left the room w/ renewed enthusiasm for science & a keener appreciation of the importance & relevance of our work as scientists https://t.co/iBVauoUGQV

Today, we honor the legacy of Maxine Singer, a distinguished biologist and passionate advocate for STEM inclusion, who recently passed away at the age of 93. Singer’s remarkable career embodied a unique blend of scientific excellence and public advocacy. https://t.co/csVv3EL8qK

— Girls Who Code (@GirlsWhoCode) July 18, 2024

Obituaries

The US molecular biologist Maxine Singer made discoveries about the role of enzymes in assembling genetic material.

A leading biochemist, she helped shape guidelines in the 1970s for genetic-engineering while calming public fears of a spread of deadly lab-made microbes.

In the early 1970s, the molecular biologist led seminal discussions on the ethics and risks of genetic experimentation.

In her more than 40-year formal association with NIH, Singer made a lasting impact in nearly every area of the agency’s conduct of fundamental research as well as its administration and scientific workforce recruitment.