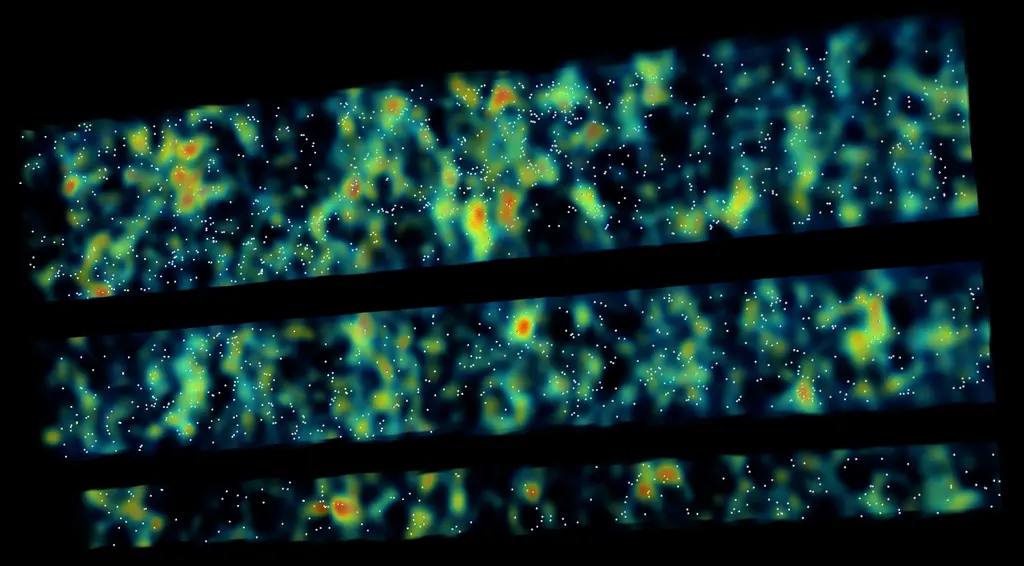

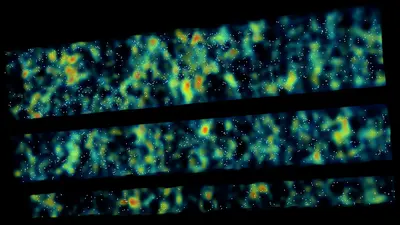

Using the Magellan telescopes at Carnegie’s Las Campanas Observatory in Chile, a research team led by Carnegie’s Andrew Newman deployed a new strategy for finding protoclusters—some of the earliest known structures in the cosmos, which are notoriously difficult to spot. The team was able to look for shadows cast by intergalactic hydrogen gas from within protoclusters onto the galaxies behind them. Credit: Andrew Newman/Carnegie Science.

Stellar streams are the shredded remains of neighboring small galaxies and star clusters that are torn apart by the Milky Way. These remnants continue to move together in long, arcing threads, orbiting around our galaxy. Carnegie astronomers Ana Bonaca and Joshua Simon, among others, study stellar streams to better understand dark matter—the mysterious substance that makes up 80 percent of the universe. Stellar streams can also reveal information about the Milky Way’s formation history, showing how it has steadily grown over billions of years by shredding and consuming smaller stellar systems. Credit: James Josephides and the S5 Collaboration.

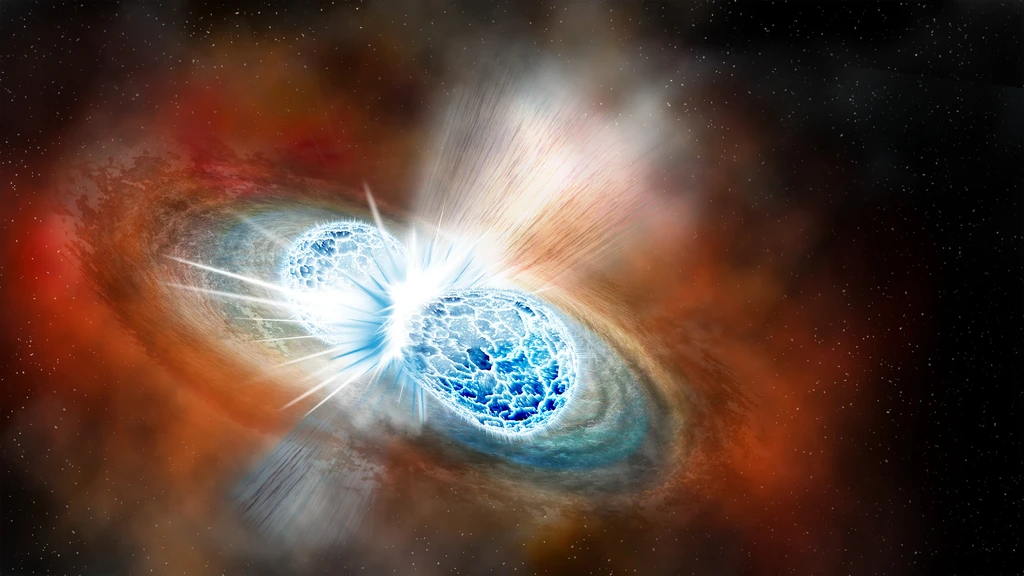

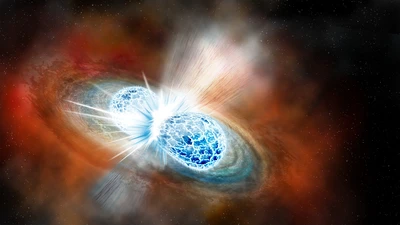

Neutron stars are the incredibly dense remnants left behind after supernova explosions. They are as close as you can get to a black hole without actually being a black hole. Just one teaspoon of a neutron star weighs as much as all the people on Earth combined. Theoretical astrophysicists have speculated for years about what happens when two of them merge, but until 2017 the phenomenon had never been witnessed. A team of Carnegie and UC Santa Cruz scientsts were the first to see the explosion using the Swope telescope at Las Campanas Observatory. Credit: Robin Dienel/Carnegie Science.

This image shows a map of intergalactic hydrogen where yellow-to-red represents high density regions and blue-to-black indicates areas of low density.

Artist’s representation of our Milky Way galaxy surrounded by dozens of stellar streams. These streams were the companion satellite galaxies or globular clusters that are now being torn apart by our galaxy’s gravity.

Artist’s concept of the explosive collision of two neutron stars.

“Every day Carnegie researchers are pursuing connections between the origins and evolution of cosmic structures—from galaxy clusters to planetary systems—and the stellar forges where the ingredients for life are manufactured,” said President John Mulchaey.

These exciting research directions not only deepen our knowledge about the cosmos, they also create opportunities for interdisciplinary collaboration between Carnegie astronomers and Carnegie Earth and planetary scientists.

Learn about three ways that Carnegie astronomers are thinking across time and space and contributing to our Blueprint for Discovery:

Light from the Ancient Universe

The first galaxies were formed a few hundred million years after the Big Bang, which started the universe as a hot, murky soup of extremely energetic particles. As the universe expanded, this material began to cool, and the particles coalesced into opaque neutral hydrogen gas. Some patches were denser than others and, eventually, their gravity overcame the universe’s outward trajectory and the material collapsed inward, forming the first stars and galaxies. Their energy excited the neutral hydrogen and ionized it, turning the lights back on in the universe. Carnegie’s Peter Senchyna used JWST to study in unprecedented detail a luminous galaxy from the era just before the universe was fully reionized. He was able to do this because it is situated behind a massive cluster of galaxies that weigh so much that they are capable of bending and magnifying light as it passes through them. This means that astronomers like Senchyna can use this cluster as a telescope to study ancient samples from the universe’s first generations of hot, massive stars. Further observations with future ground-based telescopes could reveal new details about an era of cosmic history that remains shrouded in mystery.

A New Class of Star System:

Globular clusters are spheres made up of a million stars that are bound by gravity and orbiting the center of a galaxy. Unusually, they show no evidence of dark matter—the mysterious substance that makes up 80 percent of the cosmos—and their stars are surprisingly uniform in age and chemical composition—all traits that for centuries have left scientists debating how they formed. An international team of researchers including Carnegie’s Stacy Kim recently created ultra-high-resolution simulations of the universe’s 13.8-billion-year history to probe globular cluster origins. They unexpectedly uncovered a never-previously-predicted type of star system: globular cluster-like dwarf galaxies, which have properties between those of globular clusters and dwarf galaxies. These newly identified globular cluster-like dwarf galaxies appear similar to regular star clusters in how uniform their stars’ ages and chemical compositions are when observed, but contain a significant amount of dark matter, like dwarf galaxies. Upcoming telescope surveys should be able to detect many of these globular cluster-like dwarf galaxies orbiting our Milky Way.

Naturally Occurring Space Weather Stations:

How does a star affect the makeup of its planets? And what does this mean for the habitability of distant worlds? Carnegie’s Luke Bouma recently revealed a new way to probe this critical question—using naturally occurring “space weather stations” that orbit at least 10 percent of M dwarf stars during their early lives. He and collaborator Moira Jardine of the University of St. Andrews took “spectroscopic movies” of young, rapidly rotating stars called complex periodic variables, which experience recurring dips in brightness. It turns out that these blips are due to large clumps of cool plasma that are being dragged around with the star by its magnetic field. We know that in our own Solar System, planets are affected by solar winds, magnetic storms, and other space weather coming from the Sun. However, until now, astronomers weren’t able to observe these kinds of phenomena in other systems. Looking ahead, plasma features like this will give astronomers a way to know what's happening to the material near the stars that host them—including where it's concentrated, how it’s moving, and how strongly it is influenced by the star’s magnetic field. Bouma described the work as the perfect example of a “serendipitous discovery,” something unlooked for but certain to shape new research programs in the years ahead.