For centuries, humans have returned to the same pair of questions: How did we get here? Are we alone? At Carnegie Science’s Earth and Planets Laboratory (EPL), those questions are being pursued not through speculation, but through stone.

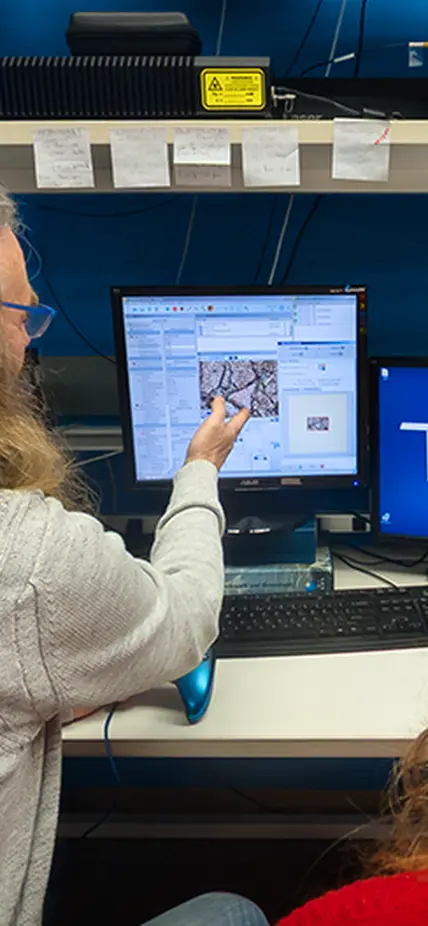

“I’m looking at a Martian meteorite,” says Andrew Steele, as he dials in the focus on an unassuming rock sample displayed on the computer screen in front of him. “And I’m looking for signs of life on Mars in here.”

The object under his lens is not symbolic. It is a literal fragment of another planet—ejected by impact, carried through space, and recovered on Earth. “Absolutely,” Steele says when asked whether a piece of Mars is truly in the room. “And you can see it here under the microscope.”

For more than two decades, Steele has studied Mars through Martian meteorites, field analogs on Earth, and two rover missions. He was a member of the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) team on NASA’s Curiosity rover, served on the science definition team for the mission that became the Perseverance rover, and is an active member of Perseverance’s SHERLOC instrument team.

“I started life as a microbiologist,” Steele says. “I think I’m an astrobiogeoplanetologist.”

That evolution reflects a defining feature of how Carnegie Science approaches discovery: moving fluidly between worlds, disciplines, and scales. Steele’s work spans microbiology, geology, chemistry, planetary science, and astrobiology—fields that are often siloed elsewhere, but deliberately intertwined at EPL.

It also mirrors the changing nature of the science itself. Mars, once written off as geologically dead, has become central not just to the question of whether life ever existed beyond Earth, but to understanding how life begins at all.

A Planet That Keeps Its Secrets

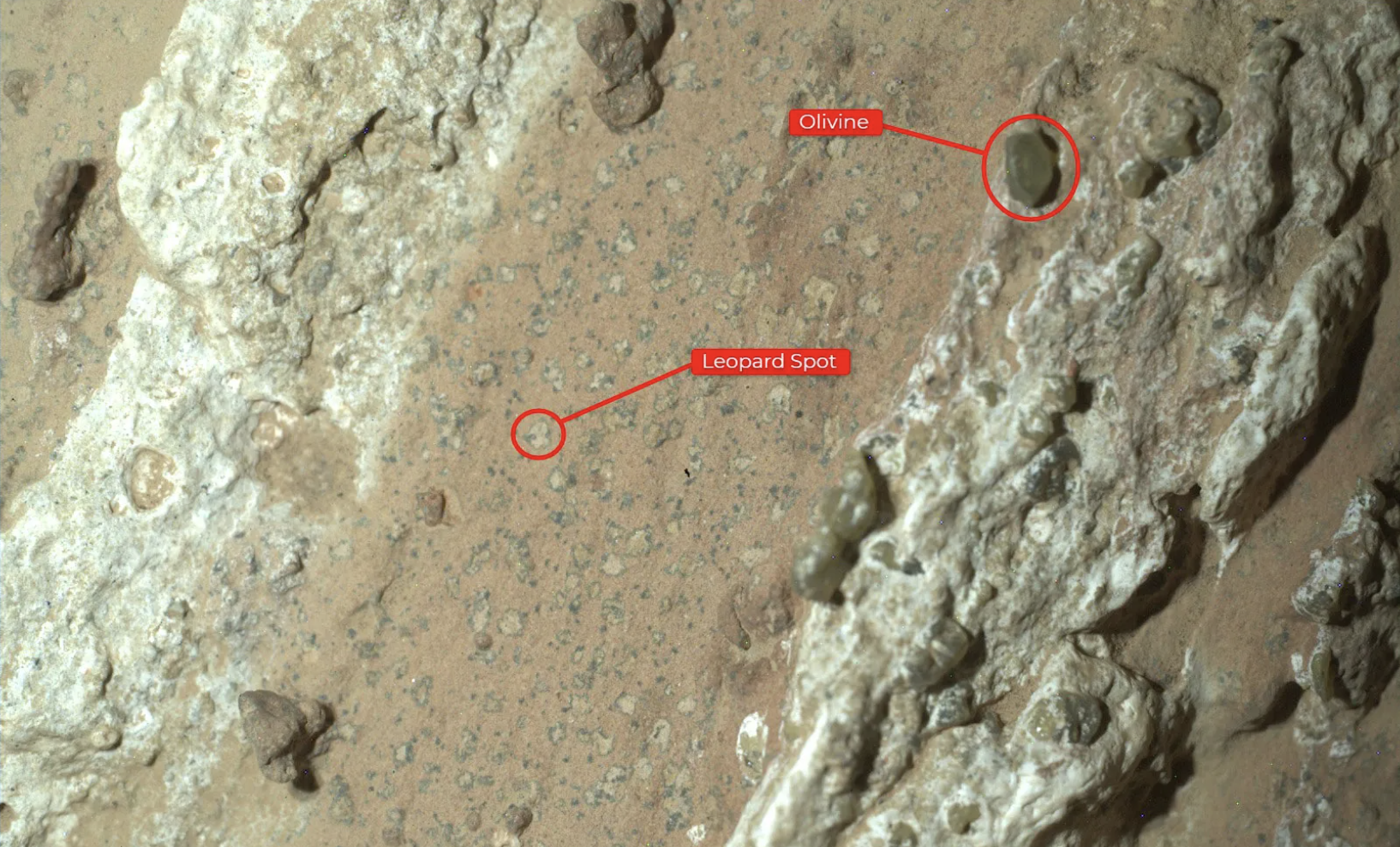

One of the most intriguing recent developments in the search for evidence of ancient life on Mars involves an unusual rock found on the Red Planet's surface. Sampled by NASA’s Perseverance rover and sourced from an ancient riverbed, the rock bore a strange pattern that scientists described as “leopard spots.”

“Where we were looking was sedimentary rock, which we don’t have any Martian samples of on Earth at the moment,” Steele says. “All the Martian meteorites we have are igneous rocks.”

Sedimentary rocks are particularly good at recording environments over time, locking chemical interactions into layered archives that—on a geologically quiet planet like Mars—may remain intact long after Earth's dynamism has erased comparable evidence.

What made this rock stand out was its chemistry.

“That sedimentary rock contains some quite interesting phosphate minerals and organic carbon,” Steele explains.

Phosphorus is essential to life as we know it. Carbon is, too. Together, they raise a provocative possibility without resolving it.

“The phosphorus itself is really important for life,” Steele says. “Finding the two together is really intriguing.”

Still, intrigue is not evidence.

“There are a lot of ways of making it with life and ways of making it without life,” Steele says. “That’s why it’s risen to the level of being a potential signature of life.”

What matters is not that the signal remains unresolved, but that it has endured. On Earth, billions of years of biological activity have overwritten the earliest chemical traces of how life began. Mars, by contrast, may have preserved them.

Why Bringing Mars Back to Earth Matters

Rovers like Perseverance can do extraordinary science—but they are limited by necessity. Steele explains why the next phase of discovery depends on returning samples to Earth.

“The rover platforms are incredibly complex spacecraft,” he says. “But the instruments in our laboratories are higher resolution and way better.”

The precedent is clear.

“Bringing the Apollo samples back from the Moon was huge for science,” Steele says. “And here we are, you know, 50, 60 years later, finding new ways to analyze them.”

He pauses, then adds: “The gift that keeps on giving.”

That long view—designing science not just for immediate answers, but for decades of reinterpretation—is part of Carnegie Science’s institutional DNA. Discoveries are not endpoints. They are starting points.

Life, Non-Life, and the Baseline Problem

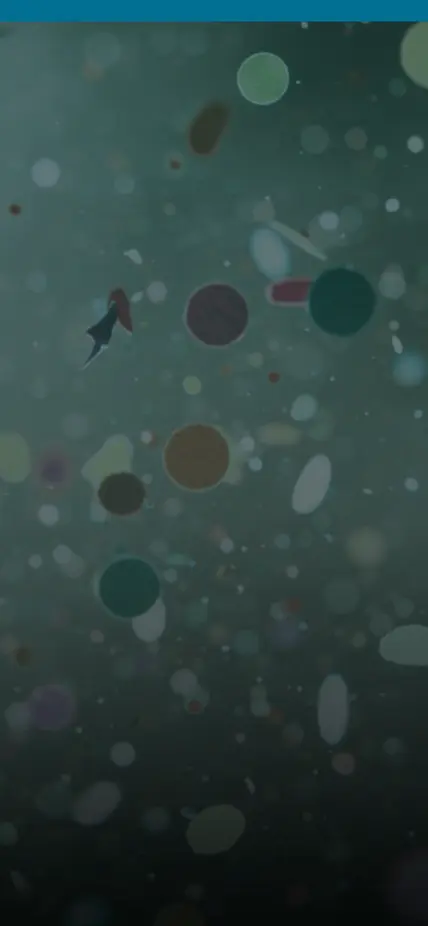

One of the hardest challenges in astrobiology is learning how to tell life apart from non-life. Steele’s work often homes in on that boundary.

“This is an analog to a Martian sample,” he says, indicating a terrestrial rock. “It shows what can happen when igneous rocks weather.”

The processes can appear strikingly lifelike—and yet are entirely abiotic.

“Water interacts with them, precipitates a whole bunch of minerals,” Steele says, “and in some cases can also precipitate organic carbon—but that’s being made by non-life processes.”

Understanding those pathways is not a detour from the search for life. It is essential to it.

“Understanding how a planet evolves with and without life enables us to set an abiotic baseline,” Steele says. “And that abiotic baseline will enable us to look for life elsewhere successfully.”

Two Questions, One Coin

For Steele, the significance of Mars extends well beyond the red planet.

“Two of the biggest questions that our species has thought about over the years is, you know, ‘Are we alone?’ and ‘How did we get here?’” he says.

This research, he argues, collapses the distance between those questions. “Exploration like this actually answers both questions,” Steele says. “They’re two sides of the same coin.”

If Mars once hosted life, then biology may be common in the universe. If it did not, Mars may still tell us something just as profound.

“If it isn’t life,” Steele says, “it’s telling us how life’s building blocks could have formed.”

And if that turns out to be the case, the implications reach far beyond our Solar System. “Who knows what we find there might be able to open doors into our understanding of exoplanets as well,” he says.

Following the Question Wherever It Leads

Steele attributes the arc of his career to an unusual degree of intellectual freedom.

“That’s what it means to be at Carnegie,” he says. “I can follow my nose.”

That freedom—to cross disciplines, to pursue uncertainty, and to ask foundational questions without needing immediate answers—has defined Carnegie Science since its founding. It is a legacy built not around single discoveries, but around a way of doing science.

“I’ve spent 20 years analyzing Mars meteorites,” Steele says. “And every day is a new day, and new things pop up all the time.”

He laughs before adding, simply: “It’s incredible.”