Advances in biotechnology have shown that the microbial world plays an outsized role in our planet’s ecological richness and drives many of its dynamic systems and cycles.

It turns out that all plants and animals exist in complex, nested ecosystems that rely on relationships with the unseen microbial landscape. These biological interactions are responsible for the health and resilience of all corners of the biosphere—from soils to oceans and forests to ice sheets.

This knowledge has rippled outward through the life sciences, endgendering a new approach to biology that focuses on community interactions between organisms and species within an ecosystem.

“For many decades, we would just study one organism at a time,” explains Yixian Zheng, the Interim Director of Carnegie’s Biosphere Sciences & Engineering division. “But through that process, we developed an appreciation of the fact that no organism in this world lives by itself.”

Zheng’s lab has a long-standing interest in genome organization and the mechanisms of cell division. Her team made many breakthroughs with implications for embryonic development, aging, and stem cell differentiation. But in recent years, Zheng has applied her vast expertise in biomedical research tools and techniques to understanding how organisms live in mutually beneficial relationships with select microbes.

“Animals and plants exist in their environment, they cope with its stresses and take advantage of the distinct opportunities it presents. This includes interacting with other organisms,” Zheng says.

Coral and Algae: A special Relationship

In 2018, Zheng and her colleagues started working to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of coral biology, with a focus on endosymbiosis between coral and photosynthetic algae.

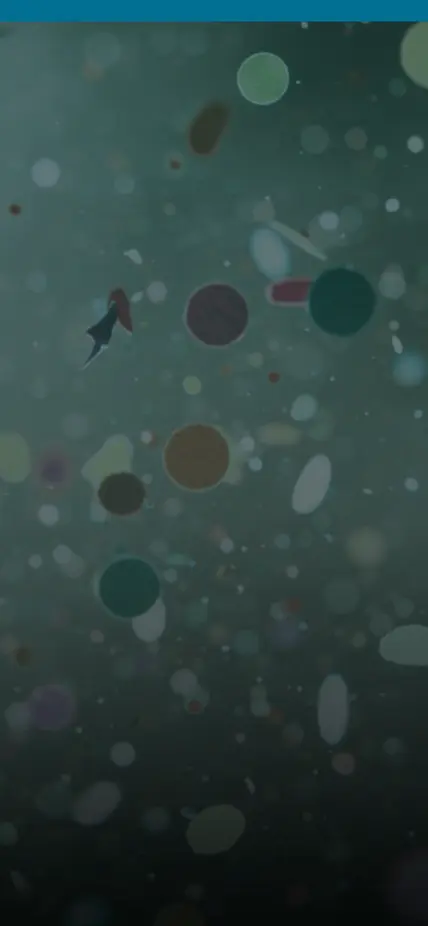

Corals are marine invertebrates that build large exoskeletons from which reefs are constructed. But this architecture is only possible because of the mutually beneficial relationship between the coral and various species of single-celled algae called dinoflagellates, which live inside individual coral cells. These algae convert the Sun’s energy into food using photosynthesis and they share some of the nutrients they produce with their coral hosts.

“The cells have to pick up the algae and live with and extract nutrients from it,” Zheng says. “That's a very cool and complicated cold living situation. And that's why we wanted to study it.”

The Biology of Resilience

Coral reefs have great ecological, economic, and aesthetic value. Many communities depend on them for food and tourism. Despite this, human activity is putting strain on these fragile communities. Warming oceans, pollution, and acidification all affect this symbiotic relationship.

That’s why it was critical to unravel the genes and cellular processes that enable healthy reefs to thrive and that could be used to promote resilience in at-risk populations.

In 2020 Zheng and her team used genomic, bioinformatic, and developmental biology tools to identify the type of cell that is required for the coral-algae symbiotic relationship to occur. They discovered that these cells express a distinct set of genes, which enable them to identify, “swallow,” and maintain an alga in a specialized compartment, as well as to prevent the alga from being attacked by its immune system as a foreign invader.

Then in 2023, Zheng’s lab revealed how coral tag friendly algae for ingestion. Better understanding how corals know which algae to take up and which to pass by is an important step for efforts to mitigate coral bleaching.

Beyond Coral

Elucidating microbial community dynamics is important for so many avenues of biological research—from understanding how bacterial hot springs survive in inhospitable environments to investigating the many ways that our own microbiome affects our health, behavior, fertility, and longevity.

“I think that, as a whole, symbiosis is a very critical field for biological research, because it underpins so many different aspects of biology, humans, other animals, and also plants,” Zheng indicates.

Looking ahead, Carnegie biologists are looking to deepen our understanding of how every microbiome is not only a community to itself, but part of an interconnected network that exists within its host’s broader array of interactions, as well as the ecosystem in which both host and microbiome are embedded. At regional and continental scales, patterns emerging from these nested relationships can be detected and modeled, informing conservation strategies.

Why Carnegie?

Zheng’s breakthrough coral research builds on Carnegie’s longstanding leadership in model system development. For decades, legendary Carnegie biologists like Don Brown, Joe Gall, and Allan Spradling developed tools to build deep expertise in understanding the mechanisms that govern life as we know it. This backbone of knowledge enabled Zheng and other Carnegie researchers to tackle a new, and challenging organism like coral.

Her career pivot research sprang from a grassriits workshop organized to build connections between Carnegie biologists and ecologists. Fieldwork experts were looking for laboratory research specialists to help them tackle existing problems with fresh eyes and new techniques. Labwork superstars like Zheng were happy to step in an develop and new way to answer big questions about coral health and resilience.

This kind of agility is a critical component of the Carnegie Science model, which empowers leading scientists with the freedom and flexibility to explore new areas of investigation and expand the frontiers of knowledge.