The Sun is Having a Moment:

As 2024 draws to a close, one of the defining scientific themes of the year was public excitement about the star at the heart of our Solar System—the Sun.

In April, North America was captivated by a total solar eclipse, which crossed Mexico, Texas, swaths of the Midwest and New England, as well as northeastern Canada.

Occurring roughly every two years, total solar eclipses happen when the Moon passes between us and the Sun, casting a shadow on portions of our planet. During this type of eclipse, locations on Earth that are in the center of the Moon’s shadow are in what’s called the path of totality. They experience a few minutes where the Moon aligns exactly with the Sun, covering it entirely.

"The path of totality often falls over the ocean. So, the eclipse on April 8 presented an exciting opportunity to engage the public about astronomy, because totality passed through so many densely populated areas," explaine Carnegie Science Observatories Outreach Coordinator Jeff Rich.

In order to capitalize on the enthusiasm about the event, Carnegie Science sent 29 astronomers to Dallas for the week to do outreach at local schools, parks, community centers, children’s hospitals, and other cultural institutions. In collaboration with the Perot Museum of Nature and Science, our experts were able to reach 32,000 North Texans in the week leading up to the eclipse.

“Access to STEM educational opportunities and scientists is so important for learners of all ages,” said Carnegie Science President John Mulchaey. “I was so proud to establish a partnership with the Perot Museum to bring information about the eclipse and eclipse safety to so many in the Dallas community.”

Did You Know?

Total solar eclipses are possible on Earth because the Sun is 400 times larger than the Moon and also 400 times farther from us. This coincidence makes the two objects appear to be the same relative size in our sky. However, the apparent size of the Sun changes throughout the course of the year, depending on our planet’s position within its orbit. Likewise, the apparent size of the Moon changes throughout the month. This means that sometimes the Moon does not entirely block the Sun, an event called an annular eclipse.

But attention on the Sun didn’t die down after the eclipse.

Thanks to increased activity due to intense solar storms in May and the Sun reaching its solar maximum period in October, many Americans were able to experience the aurora borealis for the first time in 2024.

These bright splashes of colored lights that dance across the sky are caused by charged particles shooting away from the Sun and interacting with Earth’s upper atmosphere. Because of our planet’s magnetic field, these particles are often pulled toward Earth’s poles. This means that the aurora borealis—and its southern hemisphere counterpart the aurora australis—are most often seen by those at latitudes that are closer to the poles.

However, at times of intense solar activity, the lights can be seen farther south, which is what happened on several occasions in 2024.

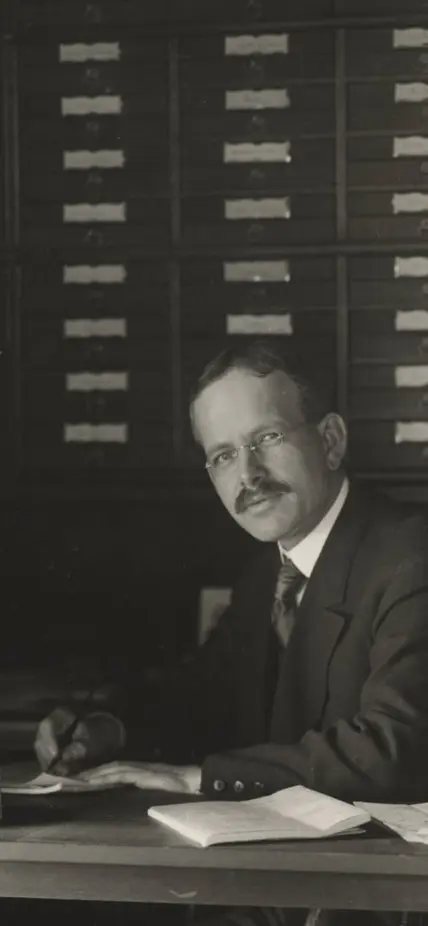

“Although Carnegie Science does not currently have any solar astronomers on staff, research on the Sun was critical to our Observatories founding,” said Mulchaey. “In 1904, George Ellery Hale convinced the institution to fund his vision for Mount Wilson Observatory, starting with a solar telescope and later expanding to include the 60-inch and 100-inch reflector telescopes.”

And solar astronomy is still an active part of daily operations at Mount Wilson. For 47 years, Steve Padilla has used the observatory’s 150-foot solar telescope to make drawings of the Sun’s surface, most of which are stored in the Carnegie Science Observatory’s archives.

Nearly every day for the better part of five decades—excluding a short interlude in the early 2000s—Padilla has contributed to a record of sunspots and solar activity that dates back to 1917. He says the length of this data set—accomplished using the same methods and tools—makes it particularly valuable to researchers from NASA and elsewhere.

“You can’t beat living up here at Mount Wilson,” Padilla concluded. “What’s better than spending your retirement days up here?”

As the solar maximum continues into 2025, he’s sure to gain new interest in his efforts.

Did You Know?

Every 11 years, the Sun’s magnetic field flips. Sunspots, which indicate the sources of solar eruptions and look like freckles on the Sun’s surface, can help scientists track this cycle. The daily sunspot drawings made at Mount Wilson Observatory cover about 40 degrees north and south of the solar equator, not the entire Sun, because sunspots mainly fall on the range of those extremes for most of the solar cycle.