Baltimore, MD—The upper gastro-intestinal tract serves as a command center in the body—receiving nutrition, coordinating digestion, and alerting the body to pathogens, according to a new study of fruit flies by Carnegie’s Haolong Zhu, Will Ludington, and Allan Spradling.

Their findings, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, indicate that these functions are highly conserved across animal species. This work will improve our understanding of how diet, stress, infection, aging and other variables affect the digestive system and its role in immune response.

For this paper, Zhu, Ludington, and Spradling undertook a deep study of the fruit fly foregut, mapping its cell types and gene expression, identifying the ways in which it interacts with other tissues and contributes to the insect’s physiological functions.

“When combined with previous studies that similarly mapped the fly’s midgut and hindgut, this latest research completes a cellular understanding of the animal’s entire digestive system,” said lead author Zhu, a Johns Hopkins University graduate student.

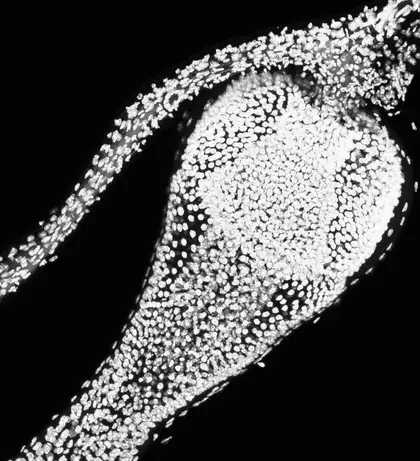

In fruit flies, the foregut consists of a complex of cellular structures located in the head and thorax.

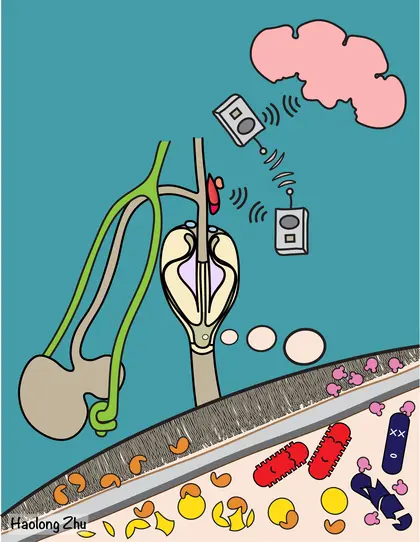

“The foregut is the first part of the gastrointestinal tract to encounter food, beneficial bacteria, and any pathogens that enter through the mouth,” explained Ludington, who has been probing microbiome acquisition and composition in the fly for nearly a decade. “Its job is to efficiently extract nutrients, retain helpful microbes, and neutralize any harmful ones. Our work shows that it serves as a command center, regulating access to the rest of the gut and coordinating input from a variety of tissues and physiological systems to ensure gut health. ”

Food enters the esophagus along with salivary gland secretions and directs it into an organ called the proventriculus, which controls entry into the intestines that form the midgut. The esophagus can also divert food into a sack-like organ called the crop, where it is stored and processed for later digestion. The proventriculus is lined by a mucosal barrier that it produces, called the peritrophic matrix, which is critical to digestive function, for controlling interaction with the fly’s microbiome.

The Carnegie team was able to characterize different types of cells within the fly foregut, infer their biological roles, and identify tools for determining the functions of their genes. Together, the information they gleaned from their research indicates how the foregut is able to act as a central coordinator for the entire digestive tract.

“By revealing the foregut at a single-cell level, we now have a detailed understanding of how the foregut is informed by and interacts with the hormonal signals and the immune system, as well as how it helps create a niche for beneficial bacterial species that form the insect’s microbiome,” said Spradling, a longstanding global leader in molecular biology who has developed breakthrough techniques in studying fruit fly genetics.

Because foregut structure and function are likely evolutionarily conserved across animals, the researchers’ findings could have implications for the human gastrointestinal system and microbiome health.