Palo Alto, CA—Evolutionary geneticist and ecologist Moises Exposito-Alonso is in Montreal representing Carnegie at the United Nations Biodiversity Conference, COP15. A session this Saturday organized by the Group on Earth Observations’ Biodiversity Observation Network, G-BIKE, and the Coalition for Conservation Genetics will discuss genetic diversity targets and projections, including a recent prediction that Exposito-Alonso published in Science.

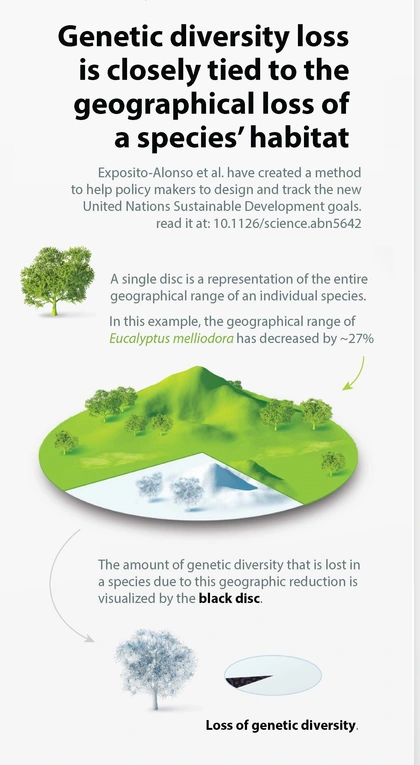

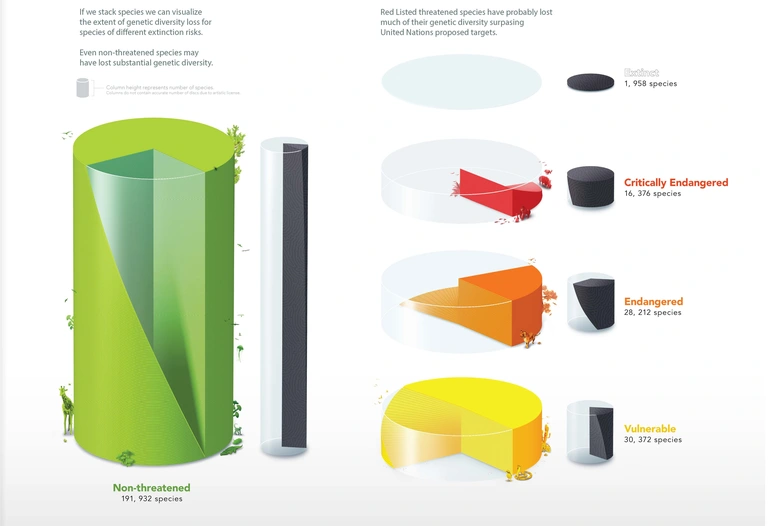

Published in September, Exposito-Alonso and colleagues created a predictive framework, which they used to illustrate that climate change and habitat destruction could have already caused the loss of more than one-tenth of the world’s terrestrial genetic diversity. These findings indicate that it may already be too late to meet the United Nations’ proposed target, preliminarily announced last year, of protecting 90 percent of genetic diversity for every species by 2030. This target is a major topic of discussion at the COP15 meeting.

“There is a great deal of enthusiasm going into the convention this week,” Exposito-Alonso who will advocate for additional protections to preserve genetic diversity. “However, there are concerns that the targets are not ambitious enough and if an agreement is not ratified, we could lose the opportunity for maximum effectiveness for another decade.”

He adds that although evaluating genetic targets may seem to many like an insurmountable challenge due to a lack of genomic data for many species, his team’s work demonstrates that there are actually ways to indirectly assess these goals at scale. This approach would also allow ownership of genetic resources to be retained nationally, an issue of concern for some parties.

In his September Science paper, Exposito-Alonso and his group analyzed genomic data for more than 10,000 individual organisms across 20 different species. He says the mathematical tool that his team developed could be calibrated in data-rich species and then expanded to make approximate conservation genetics projections for additional species, even if we don’t know their genomes.

Until recently, genetic diversity had been overlooked when setting goals for preserving biodiversity, but without a diverse pool of natural genetic mutations on which to draw, species will be limited in their ability to survive alterations to their geographic range.

In popular culture, mutations convey super powers that defy the laws of physics. But in reality, mutations represent small, random natural variations in the genetic code that could positively or negatively affect an individual organism’s ability to survive and reproduce, passing down the positive traits down to future generations.

“When you take away or fundamentally alter swaths of a species’ habitat, you restrict the genetic richness available to help those plants and animals adapt to shifting conditions,” explains Exposito-Alonso, who holds one of Carnegie’s prestigious Staff Associate positions—which recognizes early career excellence—and is also an Assistant Professor, by courtesy, at Stanford University.

Exposito-Alonso is looking forward to connecting with other participants who are working on genetic diversity from an applied perspective, including policy makers, conservationists, land managers, and others. His research is an excellent illustration of how addressing fundamental questions in science can inform planning and implementation of important global issues like the ongoing biodiversity crisis.

Dispatches From COP15

Moises Exposito-Alonso 2022_1209.mp4

Moises Exposito-Alonso 2022_1210

moi 2022_1211.mp4

Moises Exposito-Alonso Final COP15 Thoughts