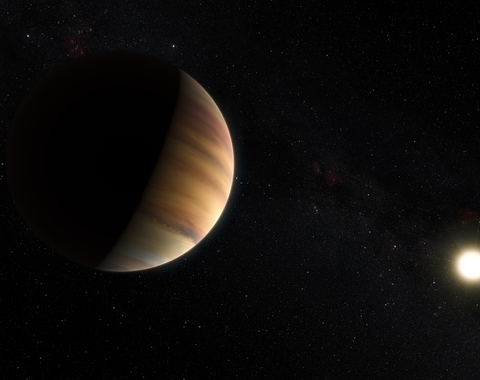

As a postdoctoral fellow at the Earth and Planets Laboratory, Kara Brugman works with Staff Scientist Anat Shahar to better understand the early years of a planet’s development. By creating molten rock—i.e. magma—in the lab under extreme temperatures and pressures, she studies the chemical composition of early planets. Ultimately, she hopes to build our understanding of how those early compositions could lead to a habitable world.

In this spotlight, Brugman talks about her recent work, discusses the importance of failure in science, and gives advice to anyone who may be looking to pursue a career in science.

To start us off, who are you and what do you study?

Hi, I’m Kara Brugman. I’m an experimental petrologist, which means I use laboratory equipment (think hydraulic presses, not Bunsen burners and glassware) to melt rocks at high pressures and temperatures. I make magma!

Currently, I’m doing experiments to learn more about the early magma ocean stage of a planet’s history. This is a stage that could have great importance for the future water budget of the planet.

Where there’s water, there could be life that we are able to recognize.

Kara Brugman uses piston-cylinder and multi-anvil presses, like the one seen here, to bring her samples to the temperatures and pressures they would experience inside of a developing planet.

What would you say is the coolest thing about your work?

The experimental apparatus I use are the coolest thing about my research: the piston-cylinder and the multi-anvil.

I use these large hydraulic presses to squeeze and melt little bits of rock. These presses can heat samples up to temperatures of 2000°C (> 3600°F) and pressures of 30 GPa (> 4.3 x 106 psi), or about the equivalent of 900 km (550 mi) deep within the Earth.

When I was starting out in geology, I had no idea that these kinds of apparatuses existed. I love to work with my hands and make things, so working in the lab with these presses really scratches that itch. Because of the industrial lubricants and hydraulic fluid we use, I often leave smelling a bit like an auto or machine shop, which I actually love.

What is the most challenging part of your work?

I think the most challenging part of any scientific research, especially research on highly ambitious projects that are quite likely not to work, is coping with constant failure and setbacks.

For example, it took over six months of failures before my current experiments worked. But, failures are a natural part of science and a necessary step toward any kind of innovation. I feel very lucky to be at Carnegie, an institution that respects and believes in the scientific process.

We had a slogan in my Ph.D. lab: Experiment, Fail, Learn, Repeat.

Sometimes the failed experiments can give you the best ideas for future research. And honestly, it is pretty hard to learn anything from an instant success, in any aspect of life.

What inspired you to choose this field of study?

I originally studied Radio/TV/Film production but when I realized I missed science, I decided to study geology.

Geology is a very broad field with many sub-disciplines. It is basically the practical application of chemistry, physics, computer modeling, and statistics—we’re not just “dirt people” (no shade to the pedologists aka soil scientists!).

I originally thought I would become a structural geologist and that I would study Mars. But taking a Petrology class—and meeting my future Ph.D. advisor when I was looking into graduate programs—made me realize that volcanoes are where it’s at!

Kara Brugman looks at a completed multi-anvil experiment. She will use information from this experiment to guide the next steps of her research.

How has your background influenced your research?

One thread that can be found throughout my various research interests is a desire to make sure we really know what we think we know. One of my undergraduate professors and member of my honors committee, Dr. Fran Bagenal, always reminded us to ask ourselves, “Does this make sense?"

I actually don’t think I have a very good bullsh*t detector, but when I do catch on that something is not quite as solid as people may think, I am very interested in figuring out that thing for real.

My first paper, "A low-aluminum clinopyroxene-liquid geothermometer for high-silica magmatic systems” is an example of this.

This project was a side quest that happened during my research at Yellowstone Caldera. I was using diffusion chronometry to determine the time between a volcanic eruption and the events that could trigger it. I realized that the tool we use to calculate the temperature of a certain mineral (clinopyroxene) was not working for the clinopyroxene I had from Yellowstone.

So, I did new experiments and combined that data with literature data to create a new thermometer for this mineral. My current research similarly takes a closer look at something that has been used for a decade now, but is being applied to a situation that’s not quite in line with the original data.

Kara Brugman sits at a picnic table on the Broad Branch Road campus, the home of the Earth and Planets Laboratory. In the background is the campus’ iconic Atomic Physics Observatory, which houses a giant—and now-defunct—Van de Graaff generator that was the first to split the atom in North America.

Why did you choose Carnegie’s Earth and Planets Laboratory?

During my Ph.D. I was a member of my department’s Women in Science Program. We met to discuss issues related to being a female-presenting person in science and academia. We also met with female visiting speakers for informal Q&As.

One of those visiting speakers was Dr. Anat Shahar, of whose lab I am now a member! She spoke very highly of EPL (then Geophysical Laboratory) and of the support postdocs are given here to pursue their intellectual curiosity. From then on, Carnegie was my first choice for a postdoc.

I still kind of can’t believe I’m here!

Do you have any advice for current graduate students?

Yes! First, find good mentors. These are not necessarily your advisor or committee members, or even people in positions “above” you. Seek out people who are doing the kinds of research you’re interested in, living the kind of life you want for yourself, or just seem like good people. It is important to have a support system (not just one person!) to turn to for advice and perspective, to vent, and to help you celebrate your successes, large and small.

Second, keep a document where you put all of your random ideas and questions. These are all potential projects/papers! If you have them in one place it will be much easier to skim through them when it’s time to think about starting something new.

Third, cultivate interests outside of science. For me, that was bouldering, hiking, puzzle hunts, and movies. For others that is cross-stitching, marathons, coloring, or baking. It doesn’t matter what it is or whether you’re “good” at it—just that you enjoy it and it helps you feel relaxed and joyful.

On the more practical side, get yourself a citation manager that has a Word or LaTeX plugin. I use Zotero. This program makes writing papers and conference abstracts SO MUCH EASIER. You don't have to manually enter any citations or type out your bibliography from a pile of sticky notes or notes scrawled in margins—these programs do this for you. Your future self will thank you.

What is one thing we might not know about you?

I help run The Secret Santa Rock Exchange, a hand sample swap that my friend Dr. Kayla Iacovino started a few years ago. People around the world sign up to exchange cool rocks with strangers.

You can follow the Exchange on Twitter @SS_RockExchange to find out when signups open for 2022!