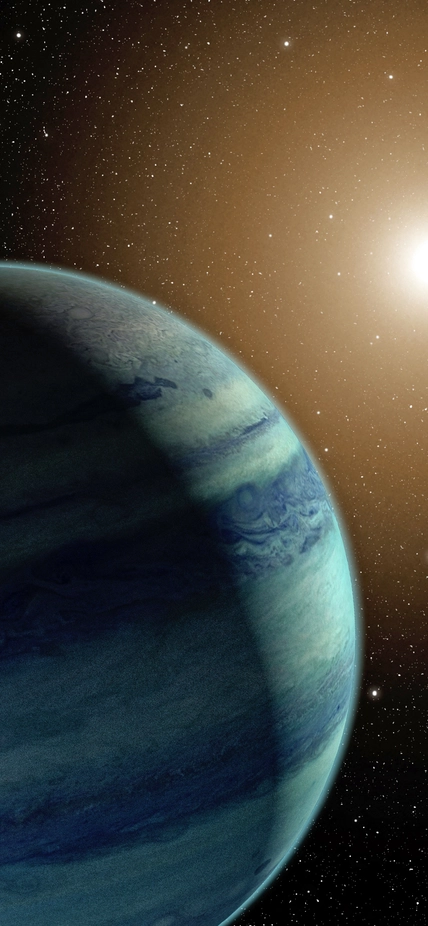

Exploring outer space to find distant planets and understand their origin

We aim to discover and understand solar and extrasolar planets through pioneering detection studies, observations of their nebular birthplaces, modeling of their formation and evolution, and using the detection of small bodies in the outer Solar System to understand the origin of our own planetary system.

Our Top Questions

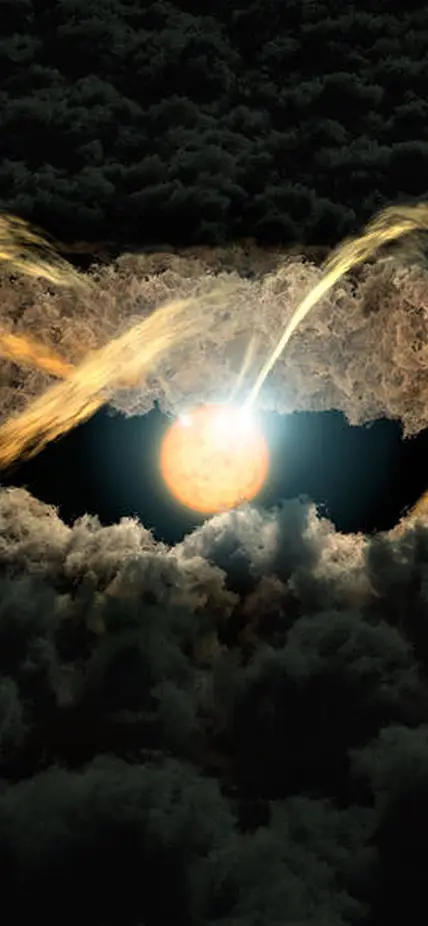

Protoplanetary disks are rotating frisbees of gas and dust created when stars form. The dust and gas ultimately coalesce to form planets that settle into orbits around their star—creating what we know as a planetary system. Understanding how these early systems go from disk to planets is essential to understanding our own origin and the true scope of our place in the universe.

From direct observation of protoplanetary disks to complex mathematical models, the astronomers and astrophysicists at the Earth and Planets Laboratory are working to piece together the mysteries of how these complex systems form.

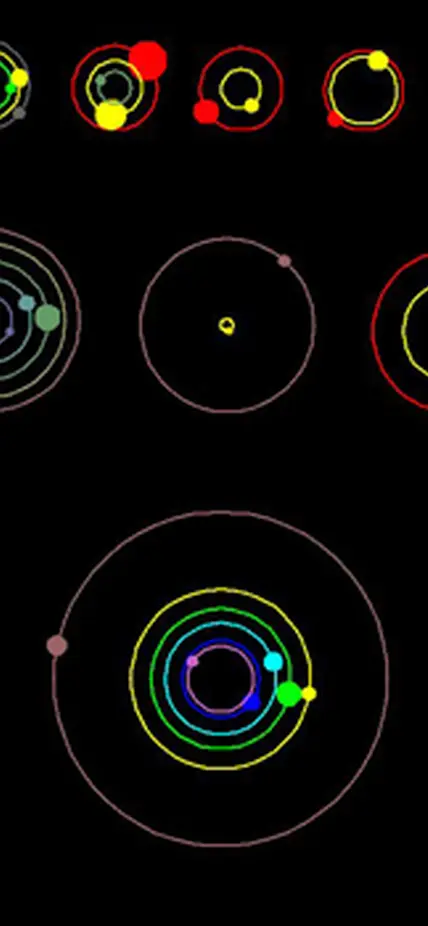

The Solar System is only one example of a planetary system. Thousands of other systems have been discovered, and most look very different than our own. Many other systems contain planets somewhat larger than Earth orbiting close to their stars where they would be too hot to support life. Giant planets like Jupiter are also quite common, but many have orbits that would prevent the existence of an Earth-like planet in a habitable orbit.

Understanding what controls the architecture of a planetary system and why observed systems are so diverse are key questions in the search for other planets like Earth.

Learn more

Planets are the only place where we know that life can thrive. However, not all planets are habitable. Many factors could affect habitability, including composition, surface temperature, presence of a magnetic field, and stellar activity.

Determining what makes a planet habitable and finding habitable planets is the ultimate goal of the Carnegie Planets interdisciplinary research project. Much of the astronomy and astrophysics work (as well as interdisciplinary studies across the EPL campus) is dedicated to exploring the question of planetary habitability.

Learn more

Ever since Carnegie astronomer Paul Butler confirmed the existence of the first extrasolar planet orbiting a sun-like in 1995—a “hot Jupiter” called 51 peg b—exoplanetary science has been on the rise! Since that first discovery, scientists have found more than 4,300 planets orbiting stars other than our own. Today one of the main focuses of scientists at the Earth and Planets Laboratory remains the discovery of these planets—particularly the search for Earth-like planets around sun-like stars.

Learn more

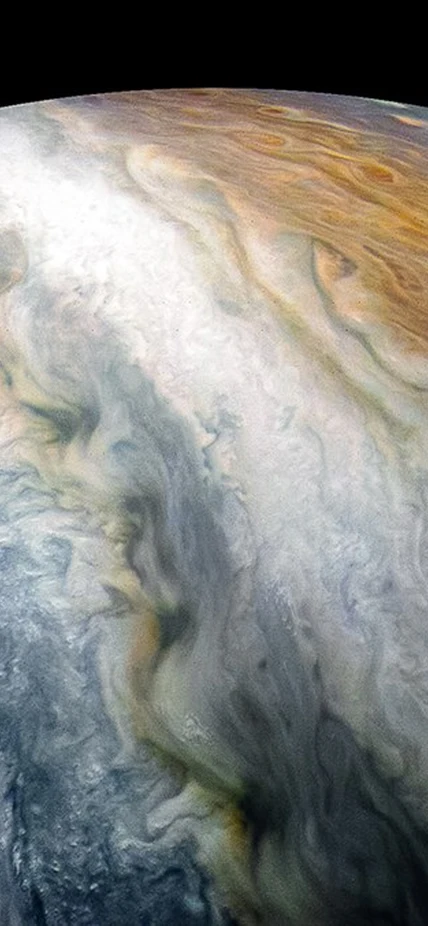

Massive and gassy, Jupiter and Saturn are planets most people know. But perhaps what many people don't know is that similar gas giants are quite common in other planetary systems. Scientists are currently studying how these planets form, and why they can be found in locations and orbits much different than in our system. That mystery is one of the toughest problems in planetary science.

Learn more

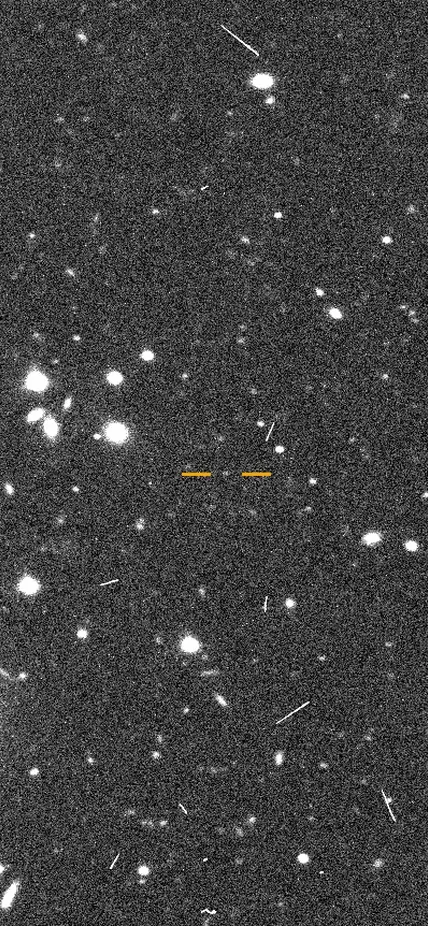

One of the biggest mysteries in our Solar System is what objects exist past Pluto in the far, dark reaches of our Sun's gravitational pull.

The Kuiper Belt, where Pluto lives, is a region of comet-like objects just beyond Neptune. This belt of objects has an outer edge, which we are only now able to explore in detail. For the past few years, astronomer Scott Sheppard and his colleagues have been performing the largest and deepest survey ever attempted to search for distant Solar System objects.

Tools of the Trade

All astronomers at EPL have access to Carnegie's Las Campanas Observatory, including the twin 6.5 m Magellan Telescopes, the 100-inch du Pont Telescope, and the 40-inch Swope Telescope.

Theoretical astrophysicists have access to high-performance computing systems—both on campus and CalTech HPC.

The Astronomy Library holds materials in stellar/galactic astronomy and exoplanet research.