The first exoplanet orbiting a Sun-like star was discovered in 1995, forever altering humanity’s perception of our place in the cosmos. In the intervening years, exoplanet research has exploded into one of the hottest topics in astrophysics.

Thanks to space missions, advances in ground-based telescopes and instruments, and the tremendous hard work and enthusiasm of the exoplanet research community, we have identified more than 6,000 worlds in our Milky Way galaxy alone.

But how can we determine which objects from this diversity of distant worlds could be capable of hosting life? Well, trying to figure out whether they have atmospheres is a great place to start answering that question.

They’re Not Like Us

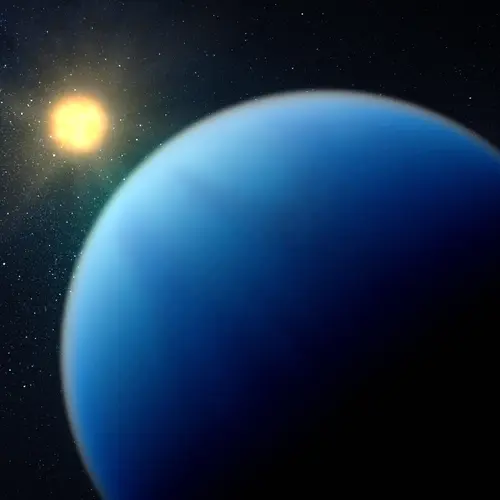

When it comes to questions about habitability, one class of exoplanets is of particular interest to astronomers. Called sub-Neptunes, they are unlike anything in our own solar neighborhood.

“There are two types of planets in our own Solar System—rocky planets like our own, which orbit closer to the Sun, and gas giant planets that orbit further out,” Vissapragada says. “But we don’t have anything between those two groups.”

However, the past three decades of planet-hunting adventures have revealed a large number of these in-between worlds that are more massive than Earth and smaller than Neptune.

Vissapragada explains: “It turns out that among the wide range of exoplanetary systems out there, those planets are really common. And we have no idea what they’re like.”

The mysteries surrounding sub-Neptunes intrigue him and other exoplanet experts.

Should we think about them as “scaled down” versions of gas giants like Neptune? Or are they “scaled up” versions of rocky planets Earth? Some astronomers think they have steam atmospheres. Others propose they have liquid water oceans under hydrogen-helium atmospheres.

Tools of the Trade

Vissapragada’s research is deepening our understanding of planetary atmospheres and helping astronomers make sense of the vast diversity of worlds out there.

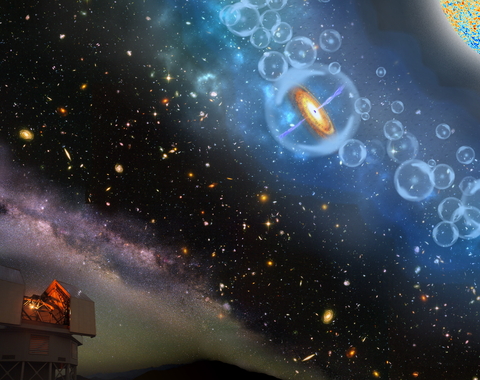

To accomplish his investigations, he uses a range of observational methods and tools, including the Hubble Space Telescope, JWST, and, most recently, the WINERED spectrograph on the Magellan telescopes at Carnegie’s Las Campanas Observatory.

Spectrographs like WINERED take light from a star and break it up by wavelength into a rainbow of colors. This can tell astronomers about the star’s characteristics.

And when a planet’s orbital path carries it between our telescopes and the star, we can also use spectroscopy to learn about its attributes.

“When planets pass in front of stars, they block out a little bit of that light. And by analyzing the colors of that transit event, we can try to deduce whether those planets have atmospheres or not,” Vissapragada says. “And the WINRED spectrograph in particular is this really powerful new facility that we have here at Carnegie for making this exact measurement.”

Alien Astronomers?

So far, exoplanet discoveries have shown how different our own Solar System is from the vast array of other worlds out there. We’ve found ocean planets and lava worlds, planets with metallic skies and planets with diamond rain, not to mention the ultra-low-density super-puffs that seem to resemble cotton candy.

But we haven’t seen anything like our own Earth.

Could an instrument like WINERED on another planet be able to identify Earth as an inhabited planet?

“We can, at this point, detect planetary systems that have planets like Jupiter and maybe Saturn,” Vissapragada answers. “But detecting planets that look like Earth is still quite challenging.”

Early Adopters

Just because we can’t detect Earth-like exoplanets now, doesn’t mean we aren’t working on it. Carnegie astronomers and instrumentation specialists are continually developing projects to improve our seeing power and advance that next big breakthrough in understanding planetary habitability.

Carnegie was an early investor in exoplanet science, back before it was astronomy’s coolest discipline. And that early commitment to advancing our knowledge of distant worlds continues to pay off. This long-standing expertise enables us to bring world-class instruments like WINERED to our telescopes and to recruit top talent like Vissapragada to join our institution.