In July 1932, young pathology resident Elizabeth M. Ramsey was performing a routine autopsy with a colleague at New Haven Hospital when she made an extraordinary discovery: an apparently normal human embryo that was just 14 days old—one of the youngest embryos known at the time. This remarkable specimen would become known as the Yale embryo, the second object in our #Carnegie125 celebration.

The embryo was tiny, with its outermost membrane, or chorion, measuring only 2.75 x 1.9 x 0.76 mm—so small that a colleague initially mistook it for an insect. Yet this was no insect, but a precious window into the earliest stages of human development. Initial study by Ramsey and her mentor, Raymond Hussey, determined it to be very close in age to the youngest non-pathogenic embryo yet studied. Such a valuable specimen, everyone agreed, belonged in the world's finest repository: the Carnegie Collection of human embryos at Carnegie Science's Department of Embryology.

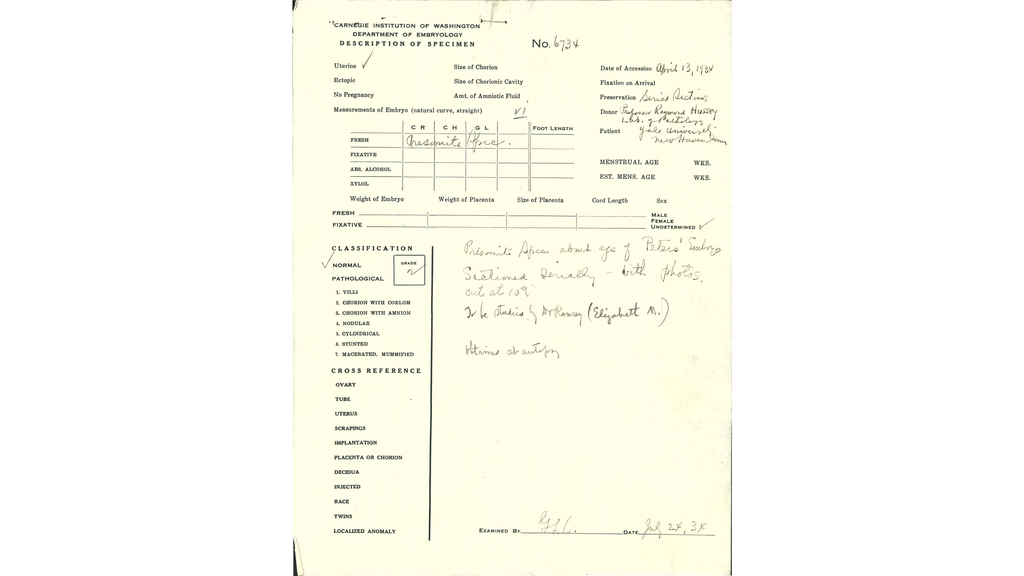

The Yale embryo, a remarkable 14-day old embryo specimen is the second object in our #Carnegie125 celebration. Credit: Carnegie Specimen 6734, Carnegie Collection, Human Developmental Anatomy Center, National Museum of Health and Medicine, Defense Health Agency (DHA), R&E, Silver Spring, MD

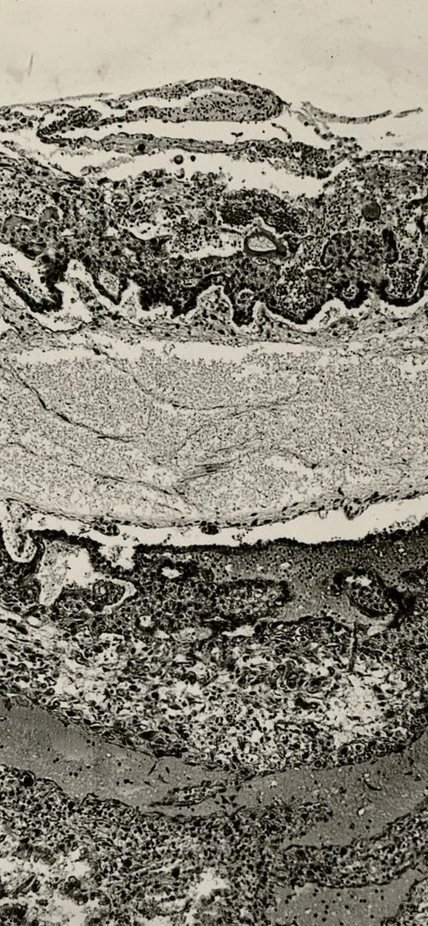

A section of the Yale embryo photographed in the 1930s. Elizabeth Ramsey discovered the extraordinary specimen while performing a routine autopsy. Credit: Carnegie Specimen 6734, Carnegie Collection, Human Developmental Anatomy Center, National Museum of Health and Medicine, Defense Health Agency (DHA), R&E, Silver Spring, MD

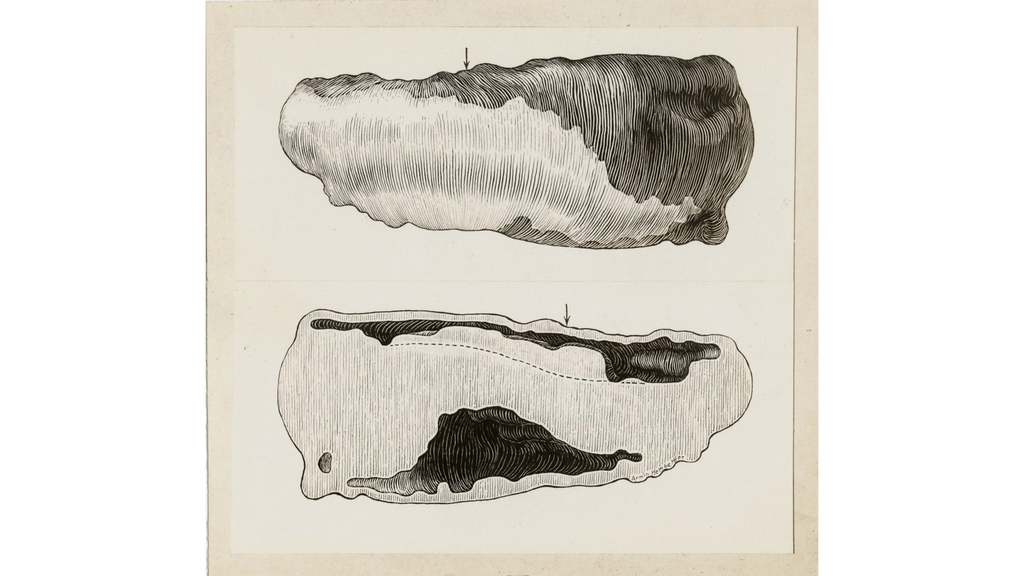

A drawing of the Yale embryo from the 1930s. The Yale embryo was a precious window into the earliest stages of human development. Credit: Carnegie Specimen 6734, Carnegie Collection, Human Developmental Anatomy Center, National Museum of Health and Medicine, Defense Health Agency (DHA), R&E, Silver Spring, MD

The sectioned Yale embryo with its storage boxes

Photographed section of the Yale embryo

Yale embryo drawing

The Carnegie Science Department of Embryology and Its Remarkable Collection

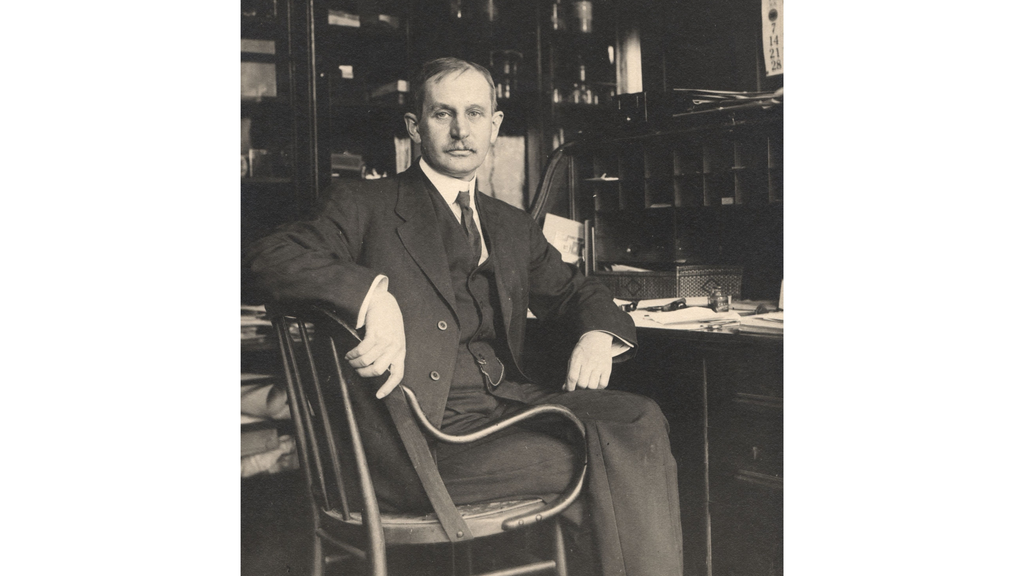

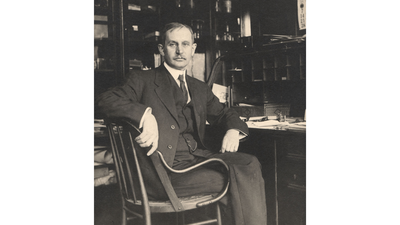

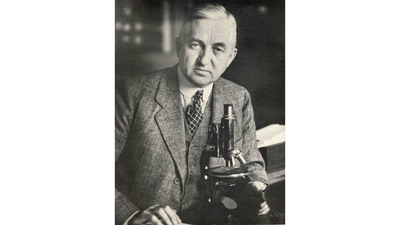

Our Department of Embryology was founded on the Johns Hopkins University campus in Baltimore in 1914. Its founding director, Franklin P. Mall, was a leader in developmental anatomy and the driving force behind what would become the Carnegie Collection, a remarkable compilation of human embryos that would serve as the centerpiece of the department’s research for half a century.

Research with the Carnegie Collection transformed our understanding of early human development by documenting how tissues and organs form, elucidating pathological changes, and establishing the authoritative standards of human embryo growth. Disseminated to physicians and utilized in textbooks, this research advanced reproductive medicine by turning embryonic development into a rigorous, evidence-based science. The discoveries made with the embryos in the Carnegie Collection still underpin much of our understanding of early development

Mall, an Iowa native who had traveled to Germany in the 1880s after medical school to study embryological techniques with Wilhelm His and Carl Ludwig, first began collecting human embryos in 1887. After joining Johns Hopkins as the university's first professor of anatomy in 1893, he continued to build his collection with embryos obtained from physicians and pathologists.

In 1913, Mall published "A Plea for an Institute of Human Embryology" in the Journal of the American Medical Association, his first public expression of his ambitious plans for his collection. He envisioned more than just a storehouse of embryo specimens; he wanted a living institution where researchers could vigorously pursue problems in anatomy, pathology, and the stages of growth in normal development. That same year, Carnegie provided its first grant to Mall to organize a laboratory “of sufficient magnitude to carry on selected problems of broad scope.” The following year, the institution's trustees officially established the Department of Embryology with Mall as its director.

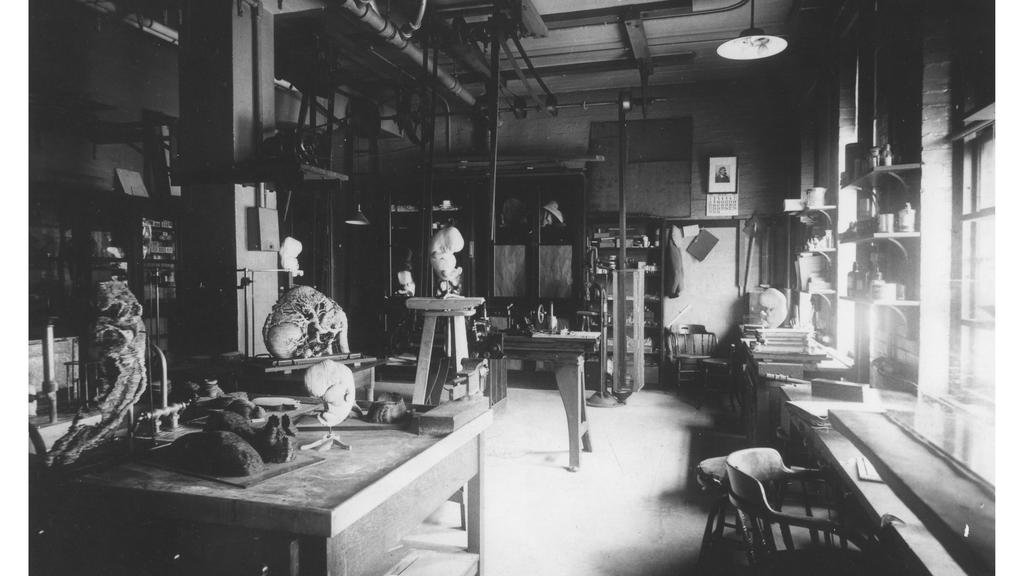

Mall set to work hiring researchers and technical staff. Construction began on a laboratory building adjacent to the Johns Hopkins Anatomy Department to house a library, microscope work room, machine shop, modeling facilities, dark rooms, and a fireproof vault to securely house the embryo specimens. By 1915, Mall had formally transferred ownership of his collection of specimens to Carnegie.

Franklin P. Mall, the founding director of the Carnegie Science Department of Embryology, was the driving force behind what would become the Carnegie Collection.

The modeling room at the Department of Embryology photographed in 1921.

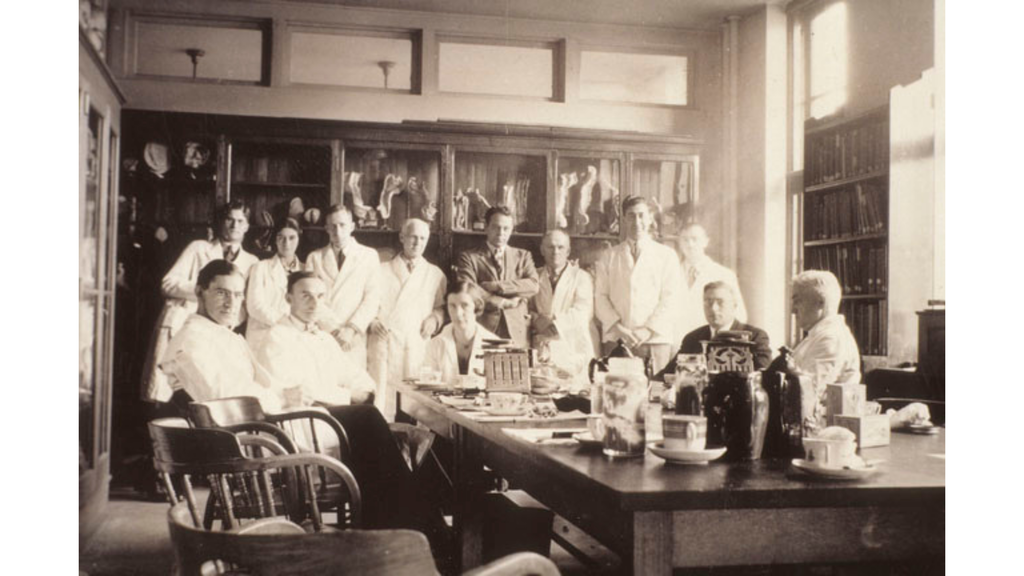

Department of Embryology staff pose for a group photograph in the lunch room in front of case of embryo models in 1935.

Department of Embryology staff pose in the vault containing the Carnegie Collection of human embryos and related records. The discoveries made with the embryos in the Carnegie Collection still underpin much of our understanding of early development.

Franklin P. Mall

Modeling room

Department of Embryology staff

Carnegie Collection vault

With Carnegie's visibility and authority, collecting accelerated dramatically. Mall reported in the 1916 Carnegie year book that while it had taken 10 years to collect his first hundred embryo specimens, five years for the second hundred, and three years for the third, specimens were now pouring in at a rate of 400 per year. Over 500 physicians across 46 states and countries had contributed to the collection, thanks to the support from gynecologists, obstetricians, and other physicians in private practice, as well as from institutions like the Maryland State Board of Public Health.

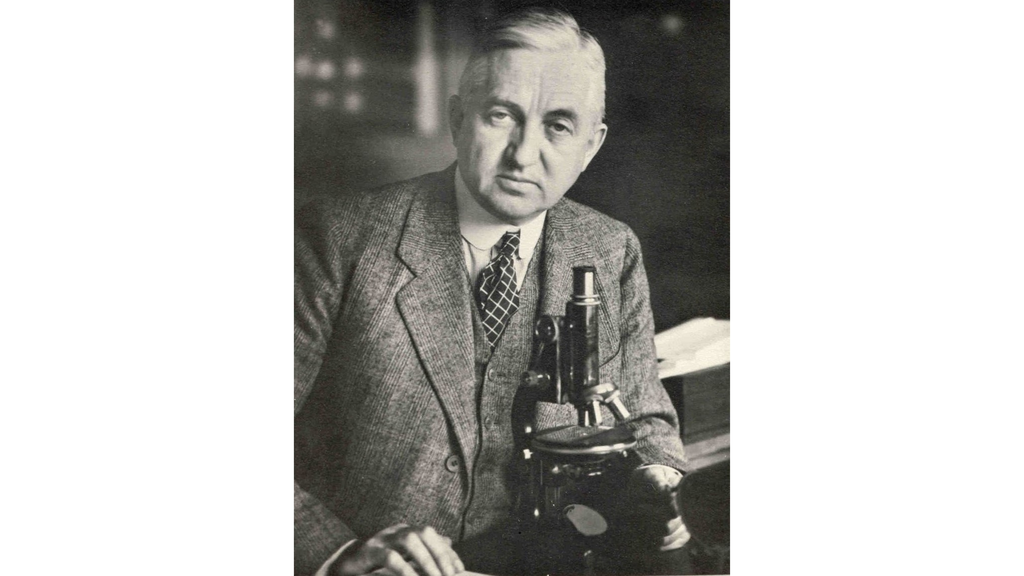

After Mall's death in 1917, his successors George Streeter and George Corner continued expanding the work. Over the next four decades, the Carnegie Department of Embryology would amass over 10,000 embryos, becoming one of the world's largest and most complete collection of human embryos.

As Streeter wrote in 1934: “Our laboratory has become a central bureau of embryological standards where an expert judgement can be obtained on developmental questions involving normal and pathological human material…With such a program one cannot stand still… It is our plan to continue unremittingly every effort toward enlarging and bettering our collection, and particularly to secure…additional and earlier representatives of the second and third week of development which important period is still incompletely known.”

Thus, the 1930s saw an intensified rush to find younger and younger embryos specimens, like the Yale embryo that could illuminate the earliest stages of human development.

From Specimen to Scientific Standard

The work of the Department of Embryology extended far beyond merely accumulating specimens. Each embryo underwent meticulous preparation and study. Skilled technical and research staff serially sectioned the fixed embryos, creating multiple thin slices that were sequentially arranged on glass slides. Each section was examined under the microscope to discover detailed information about tissues and organs. The outlines of sections were traced and reproduced in two dimensions, and from these tracings, three-dimensional plaster models were constructed. The embryos were often photographed, and illustrations were prepared by expert artists. A critical mass of specimens prepared in such a manner was an invaluable resource for comparative studies and staging.

The department's findings were published by the institution in more than 40 volumes of Contributions to Embryology spanning from 1915 to 1966. This series of descriptive embryology remains a major source of material for anatomy textbooks.

Perhaps the most enduring research achievement was the establishment of the Carnegie Stages, the definitive chronology of embryo development. First classified by Streeter, and then revised and expanded by Ronan O’Rahilly and Fabiola Müller, the final 23 developmental stages—ranging from fertilization to the eight-week fetal stage and based largely on the appearance of differentiated structures rather than size or age—remain the authoritative standard worldwide for human embryonic development.

The Department of Embryology’s second director, George Streeter, continued building the Carnegie Collection, which he used to define the Carnegie stages, the definitive chronology of embryo development. Credit: National Museum of Health and Medicine, Defense Health Agency (DHA), R&E, Silver Spring, MD

The 23 Carnegie Stages—ranging from fertilization to the eight-week fetal stage and based largely on the appearance of differentiated structures rather than size or age—remain the authoritative standard worldwide for human embryonic development.

George Streeter

Carnegie Stages

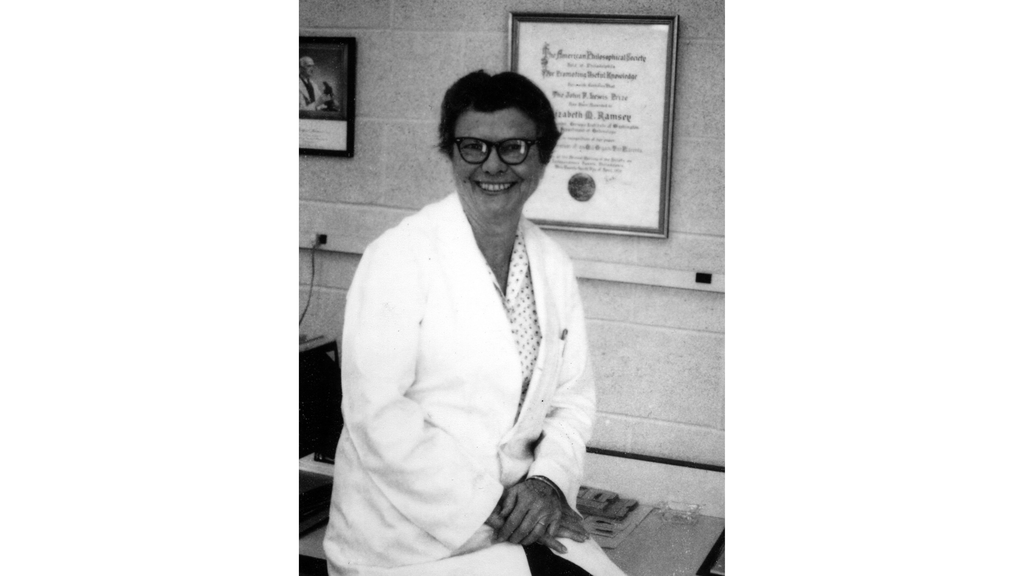

Elizabeth Ramsey and the Yale Embryo Come to Baltimore

In 1934, the Yale embryo and Elizabeth Ramsey arrived at the Department of Embryology during the golden age of embryo collecting. Hussey had presented the embryo to Streeter with the condition that Ramsey, who had recently married and planned to move to Washington, D.C., be allowed to write up the specimen. Ramsey later liked to joke that she was admitted to the department because she "came" with the Yale embryo.

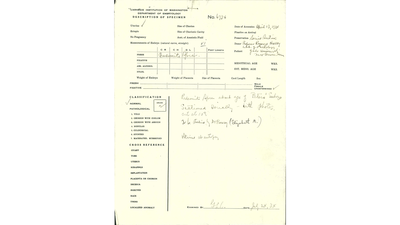

Assigned Carnegie number 6734 and a presumed age of 13-14 days, the specimen's sectioned slides and records were deposited in the fireproof vaults of the Department of Embryology building. It would eventually be classified as an example of Carnegie Stage 6a.

Ramsey, a recent graduate of Yale Medical School, where she had been one of only two women in her class, arrived in Baltimore without title and with little knowledge of embryology. Streeter gave her a desk in the noisy histology lab, where she taught herself about embryology while studying the Yale embryo. She found the work "enormously exciting" and eventually published her study in Contributions to Embryology. She stayed on at the department, later becoming the unofficial curator of the Carnegie Collection, responsible for processing and examining incoming embryo specimens.

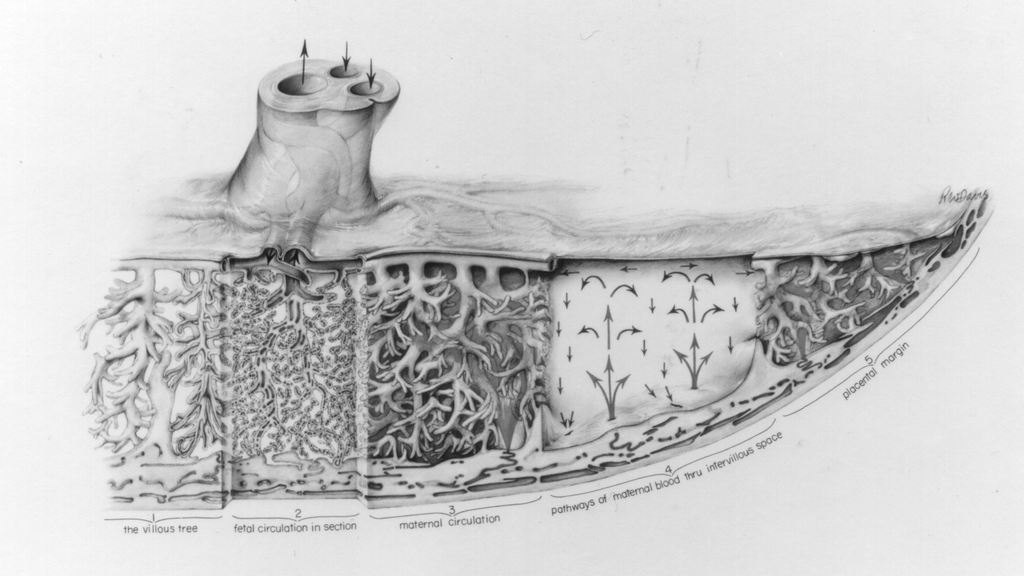

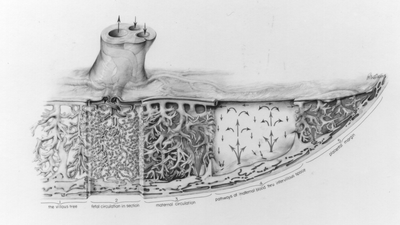

With Ramsey’s study of the Yale embryo complete, Streeter, who had begun broadening the department’s research focus, suggested that she investigate the origin of cells that drifted through the wall of the uterus. This idea opened an entirely new world of discovery for Ramsey. She went on to conduct pioneering research on placental circulation using radioactive dyes and X-rays in the emerging field of cineradiography to establish similarities between monkey and human placental systems and illuminate the interactions between the fetus, the placenta, and the mother.

Over her career, Ramsey became one of the world’s leading authorities on the structure and function of the human placenta. Her landmark studies resulted in more than 100 scientific articles and two books: The Placenta of Laboratory Animals and Man and Placental Vasculature and Circulation, co-authored with Martin Donner. Ramsey received numerous honors for her contributions. The Society for Gynecological Investigation named her Distinguished Scientist of the Year in 1987, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists gave her its Distinguished Service Award and inducted her into its Hall of Fame.

Ramsey remained a member of the Carnegie community for nearly sixty years. After 36 years at the Department of Embryology—first as a volunteer investigator, then an associate, and finally a staff member—she retired in 1971, but continued as a research associate until her death in 1993.

Elizabeth Ramsey photographed in the 1960s. Ramsey liked to joke that she was admitted to the Carnegie Department of Embryology because she "came" with the Yale embryo. Over her career, Ramsey became one of the world’s leading authorities on the structure and function of the human placenta.

Assigned Carnegie number 6734, the Yale embryo’s sectioned slides and records were deposited in the fireproof vaults of the Department of Embryology building. It would eventually be classified as an example of Carnegie Stage 6a. Credit: Carnegie Specimen 6734, Carnegie Collection, Human Developmental Anatomy Center, National Museum of Health and Medicine, Defense Health Agency (DHA), R&E, Silver Spring, MD

Elizabeth Ramsey’s placental circulation diagram. Ramsey conducted pioneering research on placental circulation using radioactive dyes and X-rays in the emerging field of cineradiography to establish similarities between monkey and human placental systems and illuminate the interactions between the fetus, the placenta, and the mother.

Elizabeth Ramsey

Yale embryo's Carnegie Collection form

Ramsey’s placental circulation diagram

A New Era and a New Home

By the time of Ramsey's retirement, the Department of Embryology’s research focus had undergone a fundamental transformation. During the 1960s, director James Ebert recognized that advances in biochemistry and genetics had opened a path to understanding development at the molecular level. As classical embryology based on morphological analysis gave way to research using molecular techniques, scientists at the department began examining how genes affect development on an even smaller scale than the tiny structures that had fascinated earlier generations of embryologists.

By 1973, the emphasis of the department had changed so much that the Carnegie Collection of human embryos was no longer actively used in its research. The collection, including the Yale embryo, was transferred to the University of California at Davis, where it was officially opened for research in 1975. Having played a major role in stewarding the collection over the decades, Ramsey attended the opening celebration. Although her own career had been built on the kinds of research now phased out at the Department of Embryology, she was positive about the change, recognizing that the role of Carnegie had been to pioneer in new areas.

“When someone else is willing and able to take over, Carnegie then takes on another pathfinding project” she explained.

In 1990, the Carnegie Collection was transferred once again to its current home at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington, D.C., where it forms the core of the museum’s Human Development Anatomy Center. There the Yale embryo and the rest of the collection of embryos and their related models, photographs, micrographs, drawings, and records remain available to researchers today.

Ramsey once called the discovery of the 14-day-old Yale embryo "the most interesting professional thing in my life." This tiny specimen, initially mistaken for an insect, had opened the door to a world of scientific discovery for Ramsey and for our understanding of human development. Today, as the second object in our #Carnegie125 celebration, the Yale embryo reminds us not only of the remarkable Carnegie Collection that served as an invaluable resource for generations of researchers, but also of the way Carnegie Science empowers researchers to pursue pioneering investigations that expand the boundaries of human knowledge.

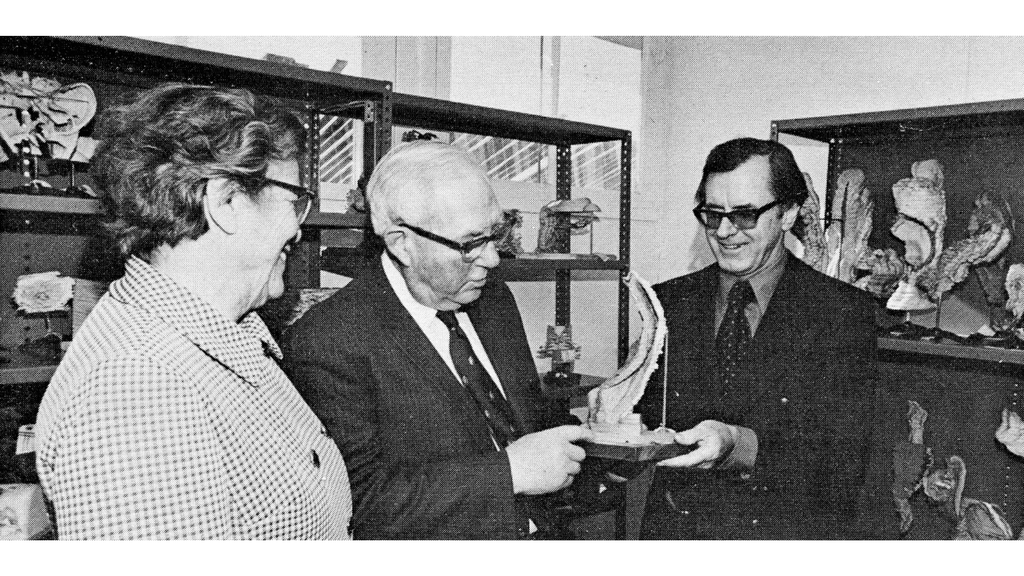

Elizabeth Ramsey and others examine an embryo model from the Carnegie Collection during the collection’s opening celebration at the University of California at Davis in 1975.

In 1990, the Carnegie Collection was transferred to its current home at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington, D.C., where it forms the core of the museum’s Human Development Anatomy Center. In this photograph from 1992, Elizabeth Ramsey is presented with a plaque acknowledging her role as a charter member of the Center’s advisory board.

University of California at Davis

Human Development Anatomy Center

Bibliography

Brown, Donald. “The Department of Embryology of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, February 1987,” BioEssays, Vol. 6, Issue 2, February 1987.

Carnegie Institution of Washington. “Carnegie Embryo Collection Transferred to National Museum of Health and Medicine.” Spectra, March 1992.

Carnegie Institution of Washington. “Carnegie Embryology Labs Open at Davis.” Carnegie Institution Newsletter, April 1976.

Carnegie Institution of Washington. “Elizabeth M. Ramsey 1906-1993.” Spectra, November 1993.

Carnegie Institution of Washington. “Profile of a Carnegie Embryologist.” Carnegie Institution Newsletter, February 1978.

Longo, Lawrence D., and Giacomo Meschia. “Elizabeth M. Ramsey and the Evolution of Ideas of Uteroplacental Blood Flow and Placental Gas Exchange." European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 90, 2000.

Maher, Brendan. “The ‘Yale Embryo’ circa 1934,” The Scientist, February 2007.

Mall, Franklin P. “Annual Report of the Director of the Department of Embryology.” in Carnegie Institution of Washington Year Book 15. Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1902.

Mall, Franklin P. “A Plea for an Institute of Human Embryology,” Journal of the American Medical Association, 60, 1913.

Noe, Adrianne. “The Human Embryo Collection” in Centennial History of CIW, Volume V: The Department of Embryology, edited by Jane Maienschein, Marie Glitz, and Garland E. Allen. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

O’Rahilly, Ronan and Fabiola Muller. Developmental Stages in Human Embryos Including a Revision of Streeter’s “Horizons” and a Survey of the Carnegie Collection. Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1987.

Ramsey, Elizabeth M. and Martin W. Donner. Placental Vasculature and Circulation. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme, 1980.

Ramsey, Elizabeth M. The Placenta, Human and Animal. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1982.

Ramsey, Elizabeth M. “The Yale Embryo,” Contributions to Embryology 27. Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1938.

Smith, Kaitlin. "The Yale Embryo," Embryo Project Encyclopedia, 2010.

Streeter, George L. “Developmental Horizons in Human Embryos. Description of Age Group XI, 13 to 20 Somites, and Age Group XII, 21 to 29 Somites.” Contributions to Embryology 30, 1942.

Streeter, George L. prepared for publication by Chester H. Heuser and George W. Corner. “Developmental Horizons in Human Embryos. Description of Age Groups XIX, XX, XXI, XXII, and XXIII, Being the Fifth Issue of a Survey of the Carnegie Collection,” Contributions to Embryology 34, 1951.

Trefil, James and Margaret Hindle Hazen. Good Seeing: A Century of Science at the Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1902- 2002. Washington, D.C.: Joseph Henry Press, 2002.

Wynn, Ralph M. “Elizabeth M. Ramsey: (1906–1993),” Placenta, 15, 1994.