An Interesting Voyage

Early Ambitions

Born in Philadelphia and raised in Washington, DC, Vera Rubin developed a fascination with the night sky as a young girl. At age 14, she built her first telescope using cardboard tubing and a store-bought lens, aiming it out of her bedroom window to track the stars. That curiosity never faded.

She earned her undergraduate degree from Vassar College—where she was the only astronomy major in her class—followed by a master’s from Cornell and a Ph.D. from Georgetown University in 1954. Throughout the 1950s and early '60s, Rubin balanced her scientific aspirations with family life, teaching, and researching while raising four children. However, by the mid-1960s, she was ready to return fully to her passion for unraveling the universe's mysteries.

Read more

A Seat at the Table

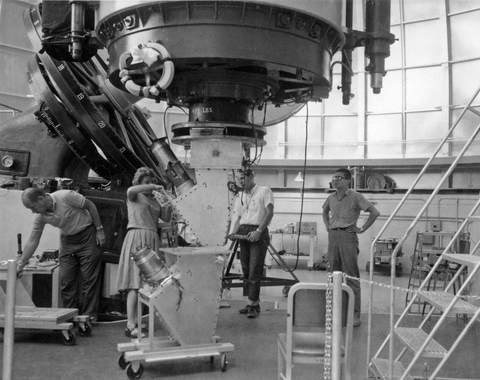

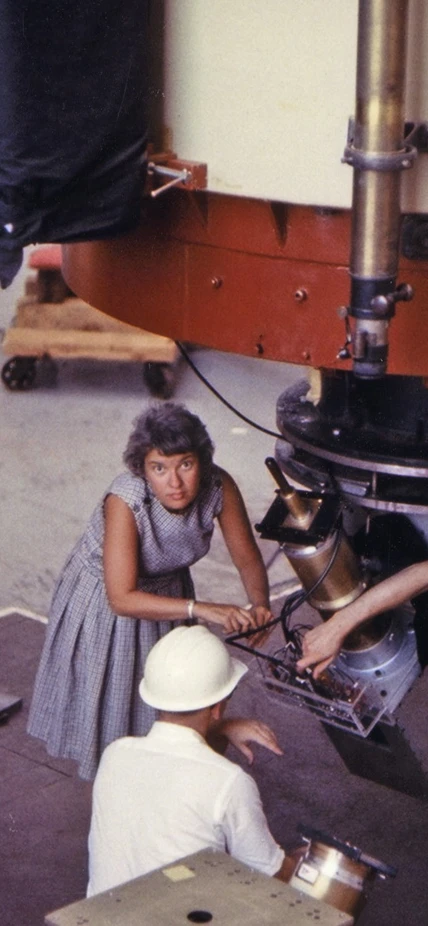

When Vera Rubin approached Carnegie’s Department of Terrestrial Magnetism in 1965, she was eager for a full-time return to hands-on research. The department was in the midst of a technological turning point, thanks to Kent Ford’s development of the image-tube spectrograph—an innovative instrument that amplified faint light from distant celestial objects, dramatically improving observational efficiency.

After asking for a job, Rubin was invited to the department’s community lunch, where Director Merle Tuve asked her to give an impromptu talk at the blackboard about her galaxy rotation research. Her command of the subject impressed Tuve, who handed her one of Ford’s photographic plates and asked her to analyze the stellar velocities it captured.

Rubin’s precise measurements and quick turnaround demonstrated her skill. Soon thereafter, she was hired on as the department’s first woman staff scientist. Her arrival marked not only a milestone in institutional inclusion but also the beginning of a collaboration that would challenge the fundamental assumptions of astrophysics.

Learn more

A Rotational Surprise and Unseen Forces

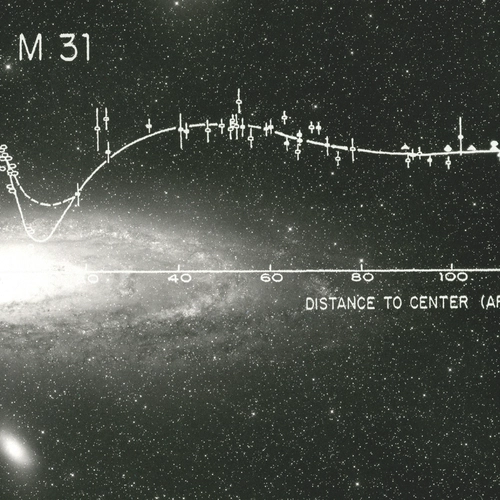

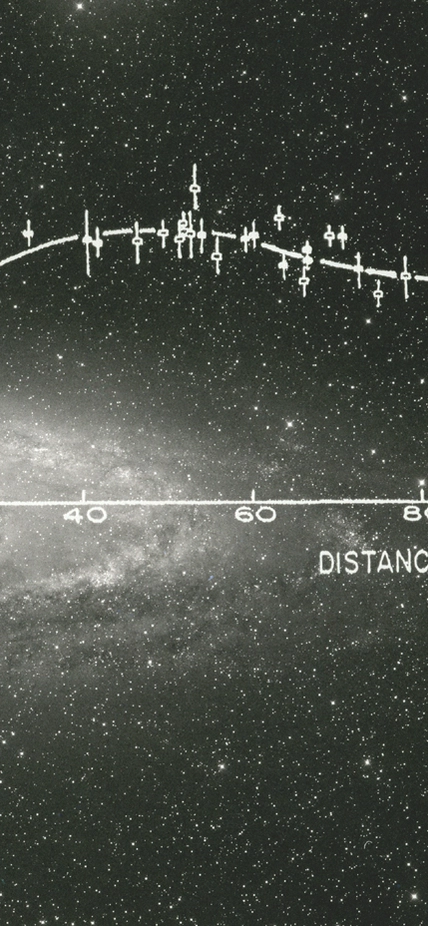

Working alongside Kent Ford, Rubin began studying the rotation of spiral galaxies, turning her sights on Andromeda.

Expectations were straightforward: stars farther from a galaxy’s center should orbit more slowly—similar to how planets in our Solar System orbit the Sun. But Rubin’s observations told a different story. Across the galaxy, stars at the edges were moving just as fast as those near the center. The data pointed to a stunning conclusion: most of the galaxy's mass was unaccounted for!

Rubin's Case for Dark Matter

Rubin and Ford’s 1970 paper on the Andromeda Galaxy’s “flat rotation curve” kicked off a scientific revolution. Over the next decade, they collected data on dozens of galaxies, consistently finding that stars at the edges were moving just as fast as those near the center—evidence for what Rubin called “non-luminous matter.” By 1980, the case for dark matter was undeniable. Rubin presented the findings to the International Astronomical Union, challenging astronomers to rethink the very structure of the universe.

Lifting Others as She Climbed

Throughout her career, Vera Rubin challenged exclusionary practices and worked to make astronomy more inclusive for women.

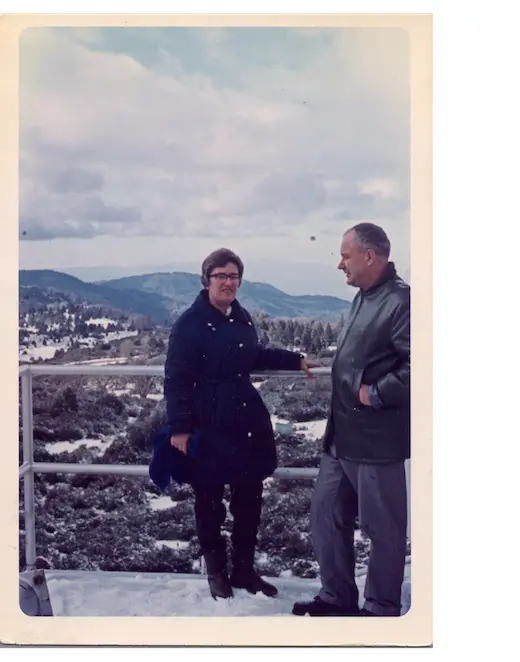

In 1965, she became the first woman officially invited to observe at Palomar Observatory. Later, she used her role in the Pontifical Academy of Sciences to advocate for greater representation of women in science on the global stage. She also pushed back against exclusionary policies at places like the Cosmos Club in DC, which had long barred women from membership.

Within the American Astronomical Society (AAS), Rubin played a foundational role in advancing gender inclusion. She co-authored a key 1973 report on the status of women in astronomy, helping to establish what would become the AAS Committee on the Status of Women in Astronomy—an ongoing force for change in the field.

Rubin’s advocacy extended to individuals, too. She mentored and supported scientists like Sandra Faber, Neta Bahcall, and Alycia Weinberger—offering guidance, writing recommendations, and regularly nominating women for awards.

Through her actions, Rubin helped change the face of astronomy—and expanded who could shape its future.

Read more

A Legacy Written in the Stars

By the time she passed away in 2016, Vera Rubin had observed over 200 galaxies and revolutionized astrophysics. Her legacy lives on in the observatory that bears her name, in the scientists she mentored, and in the ever-expanding research into the mysteries of dark matter.

Discover Things Named After Vera RubinKeep Exploring

In Memoriam

Rubin confirmed the existence of dark matter—the invisible material that makes up more than 90% of the mass of the universe.

"The American astronomer who established the existence of dark matter was 88."

“I didn't know a single astronomer, male or female,” she once said in an interview. “I didn't think that all astronomers were male, because I didn't know.”

"Astronomer Vera Rubin once told Science’s Rob Irion that “I became an astronomer because of looking at the sky” from the window of her childhood bedroom in Washington, D.C."

Remembering Vera

Vera Rubin was born the younger daughter of Philip and Rose Cooper on July 23, 1928, in Philadelphia, PA. At the age of 10, she and her family moved to Washington, DC, when her father accepted a job offer there. She graduated from Calvin Coolidge High School and received her B.A. from Vassar College. She obtained her M.A. from Cornell University and her Ph.D. from Georgetown University, where she then taught for ten years.

She arrived at Carnegie’s Department of Terrestrial Magnetism in Washington, DC, in 1965. Rubin’s interest in how stars orbit their galactic centers led her and colleague Kent Ford to study the Andromeda galaxy, M31, a nearby spiral. The two scientists wanted to determine the distribution of mass in M31 by looking at the orbital speeds of stars and gas at varying distances from the galactic center. They expected the speeds to conform to Newtonian gravitational theory, whereby an object farther from its central mass orbits slower than those closer in. To their surprise, the scientists found that stars far from the center traveled as fast as those near the center.

After observing dozens of more galaxies by the 1970s, Rubin and colleagues found that something other than the visible mass was responsible for the stars’ motions. Each spiral galaxy is embedded in a “halo” of dark matter—material that does not emit light and extends beyond the optical galaxy. They found it contains 5 to 10 times as much mass as the luminous galaxy.

As a result of Rubin’s groundbreaking work, it has become apparent that more than 80 percent of the universe is composed of this invisible material. The first inkling that dark matter existed came in 1933 when Swiss astrophysicist Fritz Zwicky of Caltech proposed it. But it was not until the work of Rubin and her colleagues that observational evidence for the existence of dark matter was demonstrated.

In 1993, Rubin received the National Medal of Science—the nation’s highest scientific award. She was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1981 and in 1996 became the first woman to receive the Royal Astronomical Society’s Gold Medal since Caroline Herschel, who was awarded the prize in 1828.

Rubin’s husband, Robert J. Rubin, a mathematician and physicist, died in 2008. The couple’s four children all acquired Ph.Ds. in the sciences or mathematics: David Rubin is a geologist; Judy Young, who died in 2014, was an astronomer; Karl Rubin is a mathematician; and Allan Rubin is a geologist.

Rubin passed away in Princeton, NJ, on the evening of December 25, 2016, at the age of 88.

Obituary: Vera Rubin Died on December 25th

THE ECONOMIST

"The American astronomer who established the existence of dark matter was 88."

From lab to Olympic podium to White House, accomplished women are still dismissed

THE WASHINGTON POST

"It’s pretty safe to say that 2016 was not the year of the woman."

Pioneering astronomer Vera Rubin dies at 88

SCIENCE AAAS

"Astronomer Vera Rubin once told Science’s Rob Irion that “I became an astronomer because of looking at the sky” from the window of her childhood bedroom in Washington, D.C. Rubin, who died Sunday at the age of 88, went on to have a long and distinguished career, including being awarded the National Medal of Science in 1993."

How Vera Rubin changed science

THE WASHINGTON POST

"Vera Rubin didn't plan to be a pioneering female astronomer. When she was 10, lying awake at her home in Washington, memorizing the paths of the stars outside her window, “I didn't know a single astronomer, male or female,” she once said in an interview. “I didn't think that all astronomers were male, because I didn't know.”

Pioneering astronomer Vera Rubin dies at 88; she helped find evidence of dark matter

LOS ANGELES TIMES

"As a woman, astrophysicist Vera Rubin had to fight just to get access to a telescope. What she saw when she did further rattled conventions: galaxies that were rotating more quickly than predicted by the laws of physics."

Remembering Vera Rubin

INSIDE SCIENCE

"Pioneering astronomer who discovered observational evidence of the existence of mysterious dark matter in the universe dies at 88."

Vera C Rubin 1928-2016

A & G FORUM

"Vera Rubin was born Vera Florence Cooper on 23 July 1928 in Philadelphia, the younger of two daughters of Philip and Rose Cooper."

Vera Cooper Rubin

PHYSICS TODAY

"Vera Cooper Rubin, who transformed our understanding of the universe by confirming the existence of dark matter, passed away on 25 December 2016 in Princeton, New Jersey. A trailblazing astronomer, a passionate champion of women in science, and an inspiring role model to generations of scientists, Rubin was loved and admired by her many colleagues and friends."

Vera Rubin: 1928–2016

SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN

"She was a vibrant role model for women in astronomy but was not defined by, nor will she be remembered for, her gender but rather by her remarkable contributions as a scientist."

Vera Rubin, Scientist Who Opened Doors for Physics and for Women, Dies at 88

THE NEW YORK TIMES

"Vera Rubin, who transformed modern physics and astronomy with her observations showing that galaxies and stars are immersed in the gravitational grip of vast clouds of dark matter, died on Sunday in Princeton, NJ, She was 88."

Vera Rubin (1928-2016)

NATURE

"Vera Cooper Rubin was a pioneering astronomer, an admired role model and a passionate champion of female scientists. Her groundbreaking work confirmed the existence of dark matter and demonstrated that galaxies are embedded in dark-matter halos, which we now know contain most of the mass in the Universe."

Vera Rubin, Who Confirmed Existence Of Dark Matter, Dies At 88

NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO

"Vera Rubin, the groundbreaking astrophysicist who discovered evidence of dark matter, died Sunday night at the age of 88, the Carnegie Institution confirms."

2016 also took one of the greatest female scientists of all time

CNN

"Vera Rubin, a pioneering astrophysicist who proved the existence of dark matter, had a gift for overcoming daunting challenges."

Vale Vera Rubin, the greatest astronomer you never heard of

THE SYDNEY MORNING HERALD

"Over the last few years I started and abandoned many, many emails to the late, great Vera Rubin, mainly because they all seemed to simply be love letters to a pioneer of astrophysics."

Vera C. Rubin: Pioneering American Astronmer (1928-2016)

PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

"Vera Cooper Rubin, an icon of astronomy whose work revolutionized our understanding of the universe by confirming the existence of dark matter, passed away on December 25, 2016 at the age of 88. Vera had a lifelong love of the cosmos."

Vera Rubin, astronomer who helped find evidence of dark matter, dies at 88

THE GUARDIAN

"Scientist from Philadelphia helped find powerful evidence of dark matter by discovering galaxies don’t quite rotate in the way they were predicted."

Johanna Teske

STAFF SCIENTIST // CARNEGIE EARTH AND PLANETS LABORATORY

I was an undergraduate intern at Carnegie DTM when I met Vera. Her office was down the hall from mine, so that every time I entered or left my office I could see hers. At that time was coming to realize I wanted to spend my life doing astronomy, but hadn’t actually had that many astronomy courses, so honestly did not know all the details about Vera’s awesome contributions. But I got to spend time with her at communal gatherings and department seminars, and always found her presence reassuring and her comments insightful. She was quiet but unintimidating, and I felt (and feel) privileged to work in the same building as her. When I needed signatures of current AAS members to join as a new member, I asked Vera and she signed my form without question. When I returned to DTM as a postdoc, Vera had moved away. I wish I had gotten to know her better earlier on. Her spirit will continue to inspire me, and many others, I’m sure.

Hannah Jang-Condell

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR // UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING

I remember starting my first postdoc at DTM just out of grad school and being in awe that Vera Rubin was just down the hall from me, but too nervous to actually talk to her. So one day she simply strolled into my office saying, "Hi, I like to meet all the new postdocs around here. I'm Vera."

She was an inspiration and a role model to me. I always loved hearing her stories and advice. She was warm and caring, but don’t be fooled by her grandmotherly appearance: she was tough as nails underneath. I miss her very much.

Peter Teuben

ASSOCIATE RESEARCH SCIENTIST // UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND

I’ve known Vera for many years. One of the last times I saw her was on her 80th birthday symposium, and a wonderful experience to see her work honored by so many colleagues.

Alicia Aarnio

GEORGE ELLERY HALE FELLOW OF SOLAR AND SPACE PHYSICS // UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO BOULDER

In 2004 and 2005, I worked at DTM as a student in the NSF REU program. Vera would sometimes come into the printer room where I worked and use the light table, pulling out glass photographic plates to analyze. I was shy and so wowed that we were doing science in the same room together, I never did ask what she was looking at- I didn’t want to interrupt or bother her. Now, I kind of wish I had asked. I later came to learn that she was warm, gracious, and never thought any question beneath her consideration. She came to the undergraduate talks and gave supportive feedback, always interested in talking to students and giving them encouragement. One of the first scientific talks I ever gave was to the star and planet researchers at DTM and she was there with productive suggestions for the project. At lunches, her wit had everyone in stitches. Vera Rubin will be greatly missed; she was a wonderful human being and a brilliant scientist.

Priyamvada Natarajan

PROFESSOR // YALE UNIVERSITY

I met Vera for the first time when I was still a graduate student in Cambridge at the October Conference in Maryland, where I was going to give an invited talk. She was incredibly warm and encouraging and of course inspiring. I was presenting results from a new technique that I had devised to map the granularity of dark matter in clusters using gravitational lensing. I was pushing the limits of even data taken by the Hubble Space Telescope then. Vera, was very excited at what I was trying to do and was enormously encouraging. We stayed in touch, often met and got dinner together at conferences and she kept abreast of the arc of my career. I particularly remember her kindness when after she found out that I was in the midst of a stressful tenure process, she called me on the phone and reassured me that my work was original and that it would all work out fine. I greatly appreciated her taking the time to do this - this is what she was really like, deeply encouraging of every young woman on the path to a career in science. Her advice to me, which I hold dear was “obstacles are simply dares...and are to be conquered not feared…”

Mordecai-Mark Mac Low

CURATOR // AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

I believe I first met her when she sat on the hiring committee founding the then brand-new Department of Astrophysics at the American Museum of Natural History. She had already served on the advisory committee that helped the Museum decide to move ahead with its founding, so her contributions to my department are quite fundamental.

Rebecca Oppenheimer

CURATOR // AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Back in ’99 or so, I had come back East for a visit from Berkeley, where I was a postdoc. I was helping to write a series of profiles in the book Cosmic Horizons with Steve Soter (one of Sagan’s students and co-author of both Cosmos series). That book came out intentionally with the opening of the Rose Center of the AMNH, where I would later work, partly because of her efforts to help found our research department there. For the book, we wanted to do a piece on her, and I went to visit her. I had actually met her several times before, as had Steve as well. But I do recall something rather unexpected when we chatted in her relatively small office at Carnegie DTM. Of course we talked about dark matter and Zwicky and Palomar, but at one point she just stopped and said, “Look, you are young. You’ve got a lot going for you and have already contributed to the field.” She paused for a moment and said, “Don’t let anyone keep you down for silly reasons such as who you are. And don’t worry about prizes and fame. The real prize is finding something new out there.” I may not be precisely quoting her, but that is what I recall, and I will never forget how sincere she was when she stared into my eyes as she said that. We talked about the elation of discovery (something I had experienced myself a just few years before) and a few of her new ideas at the time. She mainly was just such a lovely, modest, encouraging person, while being a fantastic and quite radical researcher. Firm, too. It was clear to me she could never tolerate bull$#!*.

Mercedes Lopez-Morales

STAFF ASTROPHYSICIST // HARVARD-SMITHSONIAN CENTER FOR ASTROPHYSICS

I first met Vera in 2002 at Kitt Peak. I was a graduate student at UNC Chapel Hill at the time and had been awarded my first observing proposal, which consisted of two nights at the 4-m telescope to measure the radial velocity curve of a M-dwarf eclipsing binary I had discovered for my thesis. During lunch time before my second night, Vera and her collaborator Deidre Hunter joined me at the table I was eating at, introduced themselves, and asked me if they could come up to the telescope that night to familiarize themselves with the control room, instrument interface, etc … I knew both of their names, but had never met them in person before. I could not believe I was going to be sitting next to Vera Rubin at the telescope that night!

They came by the control room as I was collecting my first target spectra that night. One of the beauties of M-dwarf stars’ spectra is that they have many, many lines, so one can measure changes in their velocity from very low signal spectra. The first thing Vera said when I showed her my data was “that just looks like noise to me!” My heart sank as I tried to explain to her how I had read somewhere that very low signal spectra was ok to measure the radial velocity signal of this type of stars. They stayed around for a while longer and then went to bed for the night. I went home next day wondering if I was going to get anything out of those data.

In 2004 I started my first post-doc as a Carnegie Fellow at DTM. On my first day at DTM I went to her office and introduced myself and Vera said “I remember you from Kitt Peak. Did you ever get anything out of those data?” I proudly showed her the beautiful radial velocity curve that had come out of those observations and she said to me “confidence and perseverance go a long way. I am impressed. You might not realize it yet, but you have what it takes to succeed in science”

We had many more conversations in the six years I was at DTM, but I will never forget those words, and I have since used them to help me through the up and downs of a career in science. Thank you Vera. You will always continue to inspire me.

Scott Trager

PROFESSOR // KAPTEYN ASTRONOMICAL INSTITUTE

A few years after I became a Carnegie Fellow in Pasadena, I visited the Carnegie Department of Terrestrial Magnetism (DTM) in Washington DC, where both my closest friend from grad school, Dan Kelson, and Vera worked. I had the opportunity to meet again with Vera, and I mentioned that Kate, my wife, was also in town, and that she was a paleoceanographer. As DTM was at the time more or less half astronomy and half geology, Vera arranged for special colloquium at DTM for Kate the very next day. What was most amazing about this was that this was one of Kate's first post-PhD colloquia anywhere, and Vera thought nothing of corralling the entirety of DTM to listen to a young, female scientist just out of grad school. I was continually floored by Vera's ability to make any young scientist, especially young women, feel as if they were the center of the scientific world, if only for a day or two. But that feeling of belonging was so important to so many of us.

RIP Vera. You were one of a kind.

Jussi Heinonen

UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI, FINLAND

I unintentionally had lunch with her at Carnegie in 2008 during my short visit related to my PhD studies. She introduced herself to me only as "Vera". We had very nice discussions about Finland and so on and only afterwards I learned who she "really" was. Such a nice person, and feet firmly in the ground. She was part of my life only for about 30 minutes, but she left an everlasting impression. Her passing is a dark matter.

Bryan Miller

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR // GEMINI OBSERVATORY

I had the tremendous good fortune to be a postdoc with Vera, Francois Schweizer, and Brad Whitmore at DTM and STScI from 1994 to 1997. It was an honor and pleasure to work with her. She was always enthusiastic and inspiring and those years were some of the most scientifically productive of my career. I fondly remember our observing runs at the Kitt Peak 4m to take spectra of counter-rotating cores in galaxies. She was always generous with her time. During one of the runs she was interviewed by Eames Demetrios for an exhibition that he was creating to commemorate the Powers of Ten video. Dinners at her house were always filled with a wonderful mix of people. I am very grateful for her advice, inspiration, and the significant impact that she had on my career. I will try to do my small part to continue her legacies of characterizing and understanding dark matter and of being a positive influence in life and work.

Nancy Grace Roman

"MOTHER OF HUBBLE" // NASA

Among many memories of Vera, whom I first met 70 years ago was of a dinner she had for Father McCarthy when the children were young. She was telling them who each if the dinner guests would be. As she went down the list, Judith asked “But mama, can men be astronomers?”

Bill Herbst

JOHN MONROE VAN VLECK PROFESSOR OF ASTRONOMY // WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY

The biggest break of my career was to be selected as a post-doc at DTM in 1976, essentially sharing an office with Vera. She kindly put up my wife and I in her home while we searched for a place that we could afford in DC. I recall a memorable dinner with Jan Oort at Vera's house. When our first child was born she bought him the cutest outfit. All this, while she was in the midst of her dark matter research, which at that time was rather frustrating to her because it was being ignored by most pundits. Many mornings she would drag me into the inner office where she had her microscope and plates and show me galaxy spectra. She would exclaim, "Are those lines straight?" referring to the emission lines that were demonstrating for anyone who cared to look that rotation curves of galaxies were flat or rising. I would patiently reply, "They are", not quite grasping the full significance of her discovery or the reason why many others at that time were refusing to acknowledge it. The biggest regret of my career is that I never published a paper with Vera. I was hired as a star formation person and while she tried hard to turn me to the dark side, I never got there. I did work with Kent Ford, however, a fine gentleman. They were quite a team. I really do not think any scientist that I encountered had a more positive mentoring effect on my own work and life than Vera. She stuck to her guns and let the facts speak for themselves as well as anyone I have known. She was truly a model scientist for us all. Thank you, Vera.

Martha Savage

DEPUTY HEAD OF SCHOOL AND PROFESSOR // VICTORIA UNIVERSITY OF WELLINGTON

I didn’t know Vera well, but I remember having lunch with her at DTM on numerous weeks-long visits in the 1980’s and 1990’s. I enjoyed our conversations and was very impressed at her accomplishments and her kindness and her willingness to help others. Since she was a mother as well as a scientist, she gave me hope that I could also do both. What a great role model!

Thank you Vera.

Bruce Doe

EMERITUS // U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY

I was a PostDoc at the Geophysical Laboratory with George Tilton back in 1960 - 1962 but used the mass spectrometers at DTM. I used to go back to DTM for visits for many years afterward and I remember Vera as a very kind person with whom I had many conversations.. I was impressed at her ability to turn out a very tasty chicken and rice dish while she was at work. Her family was as impressive as she was. Her four children all received Ph.D.s. How did that happen? I remember her fondly

Suzan van der Lee

SEISMOLOGIST, PROFESSOR // NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

While I was a postdoc at DTM from 1996 to 1998, I was privileged to be in DTM’s lunch club with Vera Rubin. Vera’s remarkably simple support had a great impact. For example, while others would make engaging conversation at lunch club, Vera always asked me how my research was going. That simple recurring question was hugely validating. It wasn’t until much later that I realized how ubiquitous that should be. Another example is when Frank Press, who used an office at DTM, was requesting input on a draft of “Understanding Earth”. I wanted to see a change in a photo caption to place a female volcanologist on equal footing with a male volcanologist, but I didn’t know how to effect the change. Vera recommended that I suggest to Frank Press the exact same caption but with the genders reversed. That simple switch made it very clear what needed to happen. While I have been and still am inspired by Vera Rubin and her scientific accomplishments, I also benefitted from her family, in particular from the mentorship of her son Allan Rubin.

Alycia Weinberger

STAFF SCIENTIST // CARNEGIE EARTH AND PLANETS LABORATORY

I was very fortunate to have the office next to Vera’s for 13 of the 49 years she was at DTM. I don’t think there was a day we were both at work that she didn’t ask me how things were going and how my family was. When she finally moved out of her office in 2014, I kept her wooden desk and a couple of her prints (copies of plates?) of beautiful galaxies to keep under its glass top just as she did. I think she told me that the desk was made by somebody at DTM in the wood shop.

It’s impossible for me to express how much her care and mentorship meant over the years. I first met her when we served on a women in science panel in 1990, when I was an undergraduate. She was the first woman astronomer I met. I’m having the video I edited of that panel transferred from VHS to DVD right now, but my recollection is that, among other things, she talked about how girls’ socialization conditions them against science early. I recall that she said she always gave copies of “The Paper Bag Princess” by Robert Munsch as baby gifts (the princess rescues the prince, and [spoiler alert], “They didn’t get married after all.”). I have now given this as a baby gift many times, though Vera gave my children a wonderful fleece star-covered onesie and “Anno’s Sundial” as baby gifts, so maybe my memory of the 1990 panel is not quite right!

We have on our campus three trees that I associate with Vera. She was very fond of gardening and trees in her own yard, but she was also an active member of DTM’s “tree committee.” She told a story that she had so annoyed a DTM Director about tree issues that he warned her trees were not worth getting fired over. In any case, there is a beautiful Crepe Myrtle tree on our campus that she had transplanted here from her yard, which it had outgrown. There are also two beautiful witch hazel bushes on our campus that always remind me of her because she went along to help pick them out (with Shaun Hardy and Mary Horan, I think). She was fascinated that one is a graft and blooms with two different colors at two different times. They often bloom in the winter and they provide a burst of color and joy to the campus, just as Vera did.

She was always humble in her personal interactions, and this is one of my favorite examples: When Kasper von Braun and I organized an “expedition” to the highest point in DC, i.e. a local hill near our campus, to watch the transit of Venus in June, 2004, Vera and Bob came. Afterwards, we were mingling with the other astronomy enthusiasts out there in the early morning, and one amateur astronomer condescendingly described his telescope setup to Vera. She just smiled and admired his equipment and I just couldn't imagine how she restrained herself. But she would never say, "I am Vera Rubin, I know something about telescopes." I'm sure the poor guy would have been thrilled to meet Vera Rubin if only he’d known, and he definitely should have been embarrassed.

When I first came to Carnegie, she told me how the staff met with the postdocs as a group every week, and asked me to take over organizing this "astronomy group meeting." We still have it today, though it morphed into a seminar series and is run by the postdocs. In the early 2000s we would take a day at the beginning to show pictures of our summer vacations. This was only the first example I saw of how Vera cared for the postdocs, and the examples in this document are wonderful.

Vera would stand up against injustice and prejudice whenever she could. She was aggravated by the few number of women who had won prizes of the AAS and been nominated to the National Academies. Every season, whe would be busy in her office nominating women herself and exhorting others to do so. I found her posts to the AASWOMEN newsletter on this topic from 2004 and 2006, where she called the statistics for women “deplorable.” She wrote, “Having your candidate win a prize is almost as good as getting it yourself.” The other issue that I remember her being very aggravated about was all (or mostly) male conference speaker lineups. I don’t recall if I counted the number of women at every meeting I attended before I met her, but I certainly did afterward.

Vera delighted in the growing number of women we had at Carnegie. She was a great recruiter. When I was offered my job - well, first, who wouldn't want to work with Vera Rubin? - I remember she would send me nice little notes, such as the cherry trees on campus are beautiful today. She made it possible for me to be hired by deciding to stop taking a salary from Carnegie and enabling DTM to hire a young person. But she wanted to be sure everyone knew she was continuing to work, not retiring, so she invented a new job title of “Senior Fellow” so she wouldn’t be emerita. When John Graham retired at about the same time, DTM hired two people -- two women!

I remember lovely dinners at Vera and Bob’s house for visiting astronomers or distinguished guests. She got to know my family over the course of various gatherings at my house, and invited us all -- my parents, siblings, husband, and sons, to dinner. My father recalls she made salmon. I remember one of these dinners where she said, let me see if I have some ice cream for dessert, and then proceeded to pull out a dozen pints from her freezer. After Bob died, I took over dinner one night, and I was shocked to discover that she didn’t have a microwave. She had a small kitchen, yet she was routinely game to host a dozen people for dinner.

I could go on and on, but I will just close by saying that I treasure the time I got to spend with her, all the mentoring I received from her, and all my memories of her.

João Alves

PROFESSOR OF STELLAR ASTROPHYSICS // UNIVERSITY OF VIENNA

My Vera Rubin story: I spent three days at DTM in Washington as part of a job interview in the late winter of 2000. By far the best memory I have was Vera's generosity towards a young post-doc working on molecular cloud structure, not her topic. She listened, asked questions, different questions from the ones I usually got, and she made me feel I was doing important work. During lunches, which brought the staff in a cosy room at DTM's ground level, she presented me to all, arranged appointments, and made sure I felt at home.

I remember vividly a long conversation in her office with an enormous photo of M31 behind her desk and a bright winter sun bathing an Indian looking carpet. She talked about the importance of observation to make progress, about her work on dark matter, her struggle as a woman in science, and her uneasiness with the unknown. Never boasting, always curious and approachable.

See you between the stars.

David Silva

DIRECTOR // NATIONAL OPTICAL ASTRONOMY OBSERVATORY

Vera was always one of my heros, her life story spoke very deeply to me and has remained one of the reasons I believe in national observatories that provide research platforms for all, no matter who they are or where they come from, via unbiased peer review. But more than that, her interactions with her colleagues, students, and family were also inspirational. I was only privileged to meet her once, when I introduced her at the 50th anniversary celebration for the founding of Kitt Peak National Observatory. That was one of the greatest honors I’ve had as NOAO Director.

Meredith Hughes

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ASTRONOMY // WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY

I didn't know Vera Rubin well, but I met her several times. One of the first talks I gave the year I got my PhD was at DTM, and I remember that Vera showed up early to the talk, introduced herself, and chatted with me about the work I was doing. Once I realized who I was talking to, I was completely astounded that this legendary scientist was taking an interest in my work. She was so curious, unassuming, and welcoming, and she just took for granted that the work that I was doing was interesting and worth talking about -- and she asked really great questions that got to the heart of the work. It sounds like a little thing, but it was one of the first times that I really felt part of a scientific community of thought. I think she made a habit of doing that for young scientists. What a brilliant astronomer and a wonderful human she was.

Wayne Warren

UMUC; TOWSON UNIVERSITY

I first met Vera in 1963 when she was at Georgetown University Observatory. I was on a tour with a group of amateurs and Vera showed us the spectrograph that she had constructed. That encounter had an influence that eventually led me into astronomy. After moving to the Washington area in 1975 after accepting a postdoc with Jaylee Mead, who was a student of Vera's, I began attending colloquia at the DTM and saw Vera often. I enjoyed talking with her at many lunches and I learned a lot from her. She was always willing to talk about things that others had an interest in. As a member of the National Capital Astronomers (NCA), I took on a project to scan the organization's publication "Star Dust" all the way back to its beginning in October of 1943. I learned from that publication that Vera Cooper had joined as an amateur in 1944 November. She joined again later and gave three lectures to the organization.

I always enjoyed hearing Vera talk about how she first became interested in astronomy. One thing that fascinated her was that when she rode in the back seat of her parents car at night, she wondered why the Moon always seemed to follow them. She was determined to eventually find the answer to that question.

When I won an astronomy prize in the early 1990s, Vera was one of the first people to congratulate me; in fact, I believe that she was the first.

My friendship with Vera has enriched my life and I will always treasure that friendship.

Stan Hart

SENIOR SCIENTIST // WOODS HOLE OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTION

I was a staff member at DTM when Vera joined in 1965. She had a broad-ranging intellect, and her creativity was undeniable. Our fields hardly intersected, but most of what I knew (and know!) about astronomy came from her informal talks and discussions at Lunch Club.

What we did share was the fact that both of our sciences involved “field work.” Mine was doing geologic studies and rock collection in random parts of the world. Hers involved seemingly endless trips to the telescopes on Kitt Peak, AZ. Talk about hard-won data! My nights in the mass-spec lab seemed quite wimpy by comparison! Vera was a wonderful colleague at DTM for 10 years, and I have frequently remembered her as I now can see Kitt Peak from my home.

Julia (Haltiwanger) Nicodemus

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR // LAFAYETTE COLLEGE

I learned that I would be spending the summer before my junior year of college interning with Vera Rubin from a voicemail message left by the director of the Carnegie Institution of Washington's summer REU program. I barely had a chance to register my excitement about being accepted into the program before having that blown away by the information that I would be working with Vera. I had to listen to the message multiple times to believe it.

Vera had to be out of town for the first few weeks of the program, so she had me come to DC early so that she could get me started. She picked me up from the train station, and I remember being so excited and nervous, wanting to impress her. She took me to her house, where I met her husband. I was really struck by how obvious and deep their love for each other was, even after over 50 years of marriage. I saw her letter from President Clinton for her National Medal of Science on the wall. I was totally star struck. We went to her office, where she had a series of buttons on display outside her door, all of which said "I Support Women in Science" in various languages. She had extra ones, which she offered to me. I took one in English and one in Spanish, both of which I still have.

I spent the summer doing calculations similar to the ones she did on the Andromeda Galaxy all those years before, demonstrating the existence of dark matter. We were looking at galaxies in the Virgo cluster, comparing normal spiral galaxies to ones with funny shapes ("disturbed kinematics"). Somewhere, there is a conference article with my name next to hers. That's pretty amazing, right? I learned so much that summer, a ton of it about astronomy and research, but that was just the start.

Vera seemed to me to be fearless. She took zero crap, pointing out sexism wherever she saw it with her unique blunt humor. The advice she gave us interns was to do what we loved, regardless of what anyone else thought, and to make trouble for the greater good. She was a hero to me on so many levels--as a feminist, as a brilliant scholar, as someone who had apparently found work/life balance, as a pioneering woman in science. I was so lucky, so privileged, to have had the opportunity to know her and learn from her. She pried open so many doors for people like me to walk through. She touched so many lives, and I will forever be grateful that mine was one of them.

Sandra Herbert

PROFESSOR // UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND BALTIMORE COUNTY

Vera Rubin entered my life when she invited me to give a talk at DTM. I’m an historian of science, and my research focuses on Charles Darwin as a geologist.

She picked up my name from some general reading she’d been doing. Thereafter I was included in the Carnegie annual events. I sensed that she was widening the circle of participation in science, and was, well, just plain curious about things herself. This morning’s New York Times (January 4) had an article by Lisa Randall entitled “Why Vera Rubin Deserved a Nobel.” It’s worth reading. I especially liked the quotation from Vera Rubin herself that she “decided to pick a problem that I could go observing and make headway on, hopefully a problem that people would be interested in, but not so interested that anyone would bother me before I was done.” This strikes me as especially good advice for anyone trying to raise children simultaneously with doing scientific research. As for prizes: it’s worth noting that Charles Darwin was never knighted.

Craig Bina

PROFESSOR // NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

My favorite memory of Vera dates to my time as a joint DTM-GL postdoc during 1988-90. One day Vera came into my office very excited. She told me that there were some unusually magnificent sunspots visible just now. Handing me a strip of exposed film (to protect my eyes), she urged me to come out to view them. She was practically skipping. So I was privileged to experience my first careful observation of sunspots in the company of a master. I swiftly came to realize that Vera was a brilliant senior scientist who had somehow also managed to retain the joy and wonder of a child. She set such a powerful example that I have retold this story many times to my own students and will undoubtedly continue to do so.

Stories compiled by Johanna Teske.

-

Vera Rubin's publications in the Astrophysics Data System (ADS)

-

The form of the Galactic Spiral Arms from a Modified Oort Theory, V. C. Rubin, Astron. J., 60, 177, 1955.

-

Solar Limb Darkening Determined from Eclipse Observations, V. C. Rubin, Astrophys. J., 129, 812, 1959.

-

Structure and Evolution of the Galactic System, V. C. Rubin, Physics Today, 13, 32 (December), 1960.

-

Faint Lines in the Arc Spectrum of Iron (Fe1), C. C. Kiess, V. C. Rubin, C. E. Moore, Washington: National Bureau of Standards, 1961.

-

Kinematic Studies of Early-Type Stars I. Photometric Survey, Space Motions, and Comparison with Radio Observations, V. C. Rubin, J. Burley, A. Kiasatpoor, B. Klock, G. Pease, E. Rutscheidt, and C. Smith, Astron. J., 67, 491, 1962.

-

The Interpretation of the K Term in the Radial Velocities of Cepheids and O and B Stars, V. C. Rubin, Astrophys. J., 138, 613, 1963.

-

Galactic Coordinates for Plate Centers of Palomar Sky Atlas, V. C. Rubin and M. F. McCarthy, S. J., Astrophys. J. Supp. No. 78, 213, 1963.

-

Classification of G Type Stars in the Near Ultraviolet Region, M. F. McCarthy, S. J., and V. C. Rubin, Specola Astronomica Vaticanag, Riceriche Astronomiche, Vol. 6, No. 19, 1963.

-

Detection of Abell's Faint Clusters on Ross-Calvert and Lick Sky Atlas Prints, M. F. McCarthy, S. J., and V. C. Rubin, Proc. Astron. Soc. Pac., 75, 197, 1963.

-

Kinematics of Early-Type Stars II. The Velocity Field within 2 kiloparsecs of the Sun, V. C. Rubin and J. Burley, Astron. J., 69, 92, 1964.

-

The Rotation and Mass of NGC 6503, E. M. Burbidge, G. R. Burbidge, D. J. Crampin, V. C. Rubin, and K. H. Prendergast, Astrophys. J., 139, 539, 1964.

-

The Rotation and Mass of NGC 3521, E. M. Burbidge, G. R. Burbidge, D. J. Crampin, V. C. Rubin, and K. H. Prendergast, Astrophys. J., 139, 1058-1065, 1964.

-

The Rotation and Mass of NGC 1792, V. C. Rubin, E. M. Burbidge, G. R. Burbidge, and K. H. Prendergast, Astrophys. J., 140, 80-84, 1964.

-

Motions in Barred Spirals VI. The Rotation and Velocity Field of NGC 613, E. M. Burbidge, G. R. Burbidge, V. C. Rubin, and K. H. Prendergast, Astrophys. J., 140, 85-93, 1964.

-

Motions in Barred Spirals, VII. The Velocity Field of NGC 925, V. C. Rubin, E. M. Burbidge, and G. R. Burbidge, Astrophys. J., 140, 94-98, 1964.

-

A Study of the Velocity Field in M82 and Its Bearing on Explosive Phenomena in that Galaxy, E. M. Burbidge, G. R. Burbidge, and V. C. Rubin, Astrophys. J., 140, 942-968, 1964.

-

NGC 2188, A Peculiar Southern Galaxy, V. C. Rubin, E. M. Burbidge, and G. R. Burbidge, Astrophys. J., 140, 1304, 1964.

-

The Rotation and Mass of NGC 7331, V. C. Rubin, E. M. Burbidge, G. R. Burbidge, D. J. Crampin, and K. H. Prendergast, Astrophys. J., 141, 759, 1965.

-

The Rotation and Mass of the Inner Parts of NGC 4826, V. C. Rubin, E. M. Burbidge, G. R. Burbidge, and K. Prendergast, Astrophys. J., 141, 885, 1965.

-

Radial Velocities of Distant O B Stars in the Anticenter Region of the Galaxy, V. C. Rubin, Astrophys. J., 142, Oct. 1965.

-

An Old Open Cluster Near the North Galactic Pole, A. R. Upgren and V. C. Rubin, P.A.S. P., Oct. 1965.

-

Low-dispersion Image-tube Spectra in the Red: 3C 33, 3C 48, Ton 256, and an Infrared Star, W. K. Ford, Jr., and V, C. Rubin, Astrophys. J., 142, 1303, 1965.

-

Quasi-stellar Objects with Small Redshifts: 1217+02, 3C 249.1, and 3C 263, W. K. Ford, Jr., and V. C. Rubin, Astrophys. J., 145, 357, 1966.

-

Faint Blue Objects in the Virgo Cluster Region, V. C. Rubin, Sandra Moore, and F. C. Bertiau, S. J., Astron. J., 72, 59, 1967.

-

Optical Observations of Radio Galaxies and Quasi-stellar Objects, V. C. Rubin, in High Energy Astrophysics, I., pp. 133-151, DeWitt, C., E. Schatzman, and P. Veron, eds., N. Y. Gordon and Breach, 1967.

-

The Spectrum of the 1967 Supernova in NGC 3389 and H-alpha Velocities in the Galaxy, V. C. Rubin and W. K. Ford, Jr., Publ. Astron. Soc. Pacific, 79, 322, 1967.

-

Radial Velocities from Image Tube Spectra, V C. Rubin, W. K. Ford, Jr., J. W. Christy, Inter. Astron. Union Symp. No. 30, 5, 1967.

-

Spectroscopic Study of the Seyfert Galaxy NGC 3227, V. C. Rubin and W. K. Ford, Jr., Astrophys. J., 154, 431, 1968.

-

Foil- and Gas-Excitation of Sodium Spectra, L. Brown, W. K. Ford, Jr., V. C. Rubin, W. Trachslim, and W. Brandt, in Beam-Foil Spectroscopy, I., pp. 45-77, S. Bashkin, ed., N. Y., Gordon and Breach, 1968.

-

Optical Spectra Near 1 Micron: the Seyfert Galaxy NGC 4151 and the Planetary Nebula NGC 6543, W. K. Ford, Jr., A. T. Purgathofer, and V. C. Rubin, Astrophys. J., 153, L39, 1968.

-

The Spectrum of the 1968 Supernova in NGC 2713, W. K. Ford, Jr., and V. C. Rubin, Publ. Astron. Soc. Pacific, 80, 466, 1968.

-

Observations of M82 in the Optical Infrared, F. Bertola, S. D'Odorico, W. K. Ford, Jr., and V. C. Rubin, Astrophys. J., 157g, L27, 1969.

-

A Note on the Systemic Velocity of M31, V. C. Rubin and S. D'Odorico, Astron. Astrophys., 2, 484, 1969.

-

A Comparison of Dynamical Models of the Andromeda Nebula and the Galaxy, V. C. Rubin and W. K. Ford, Jr., in Inter. Astron. Union Symp. No. 38, The Spiral Structure of Our Galaxy, pp. 61-68, W. Becker and G. Contopoulos, eds., Dordrecht, Holland, D. Reidel Publ. Co., 1970.

-

Rotation of the Andromeda Nebula from a Spectroscopic Survey of Emission Regions, V. C. Rubin and W. K. Ford, Jr., Astrophys. J., 159, 379, 1970.

-

Emission-line Intensities and Radial Velocities in the Interacting Galaxies NGC 4038-4039, V. C. Rubin, W. K. Ford, Jr., and S. D'Odorico, Astrophys. J., 160, 801, 1970.

-

Narrow Band Filter Photographs and Spectra of the Planetary Nebula NGC 7009, W. K. Ford, Jr., and V. C. Rubin, Astrophys. Lett., 8, 67, 1971.

-

A Comparison of 21-CM Radial Velocities and Optical Radial Velocities of Galaxies, W. K. Ford, Jr., V C. Rubin, and M. S. Roberts, Astron. J., 76, 22, 87, 1971.

-

Radial Velocities and Line Strengths of Emissions Lines Across the Nuclear Disk of M31, V. C. Rubin and W. K. Ford, Jr., Astrophys. J., 170, 25, 1971.

-

A Finding List of Faint Blue Stars in the Anticenter Region of the Galaxy, V. C. Rubin and J. M. Losee, Astron. J., 76, 1099, 1971.

-

Gas in the Nucleus and Disk of M31, V C. Rubin and W. K. Ford, Jr., in Intern. Astron. Union Symp. 44, External Galaxies and Quasi-stellar Objects, pp. 49-55, D. S. Evans, ed., Dordrecht, Holland, D. Reidel Publ. Co., 1972.

-

Variation of Emission-line Strengths Across M31, V. C. Rubin, C. K. Kumar, and W. K. Ford, Jr., Astrophys. J., 177, 31, 1972.

-

The Dynamics of the Andromeda Nebula, V C. Rubin, Scientific American, 228, 30, 1973.

-

Early Observations of the Crab Nebula as a Nebula, V. C. Rubin, R. J. Rubin, Bull. Am. Astron. Soc., 5, 411, 1973.

-

Stellar Motions Near the Nucleus of M31, V. C. Rubin, W. K. Ford, Jr., and C. K. Kumar, Astrophys. J., 181, 61, 1973.

-

Line Intensities and Radial Velocities for 12 Planetary Nebulae, S. D'Odorico, V. C. Rubin, and W. K. Ford, Jr., Astron. Astrophys., 22, 469, 1973.

-

Astronomy Spoken Here, V. C. Rubin, in Language and International Studies, K. R. Jankowsky, ed., Washington, D. C., Georgetown Univ. School of Languages and Linguistics, pp. 139-143, 1973.

-

A Curious Distribution of Radial Velocities of ScI Galaxies with 14.0 m 15.0, V. C. Rubin, W. K. Ford, Jr., and J. S. Rubin, Astrophys. J., 183, L111, 1973.

-

Klemola 30: A Group of Interconnected Galaxies, J. A. Graham, and V. C. Rubin, Astrophys. J., 183, 19, 1973.

-

Two Chains of Interesting Southern Galaxy: NGC 7172-73-74-76 and NGC 7201-03-04, V. C. Rubin, Astrophys. J., 191, 645, 1974.

-

Second Finding List of Faint Blue Stars in the Anticenter Region of the Galaxy, V. C. Rubin, D. Westpfahl, Jr., and M. A. Tuve, Astron. J., 79, 1409, 1974.

-

Report to the Council of the AAS from the Working Group on the Status of Women in Astronomy, A. Cowley, R. Humphreys, B. Lynds, and V. Rubin, Bull. Amer. Astron. Soc., 6, 412, 1974.

-

Physical Conditions and Structure in NGC 7293, J. W. Warner, and V. C. Rubin, Astrophys. J., 198, 593, 1975.

-

Observations of NGC 6764, A Barred Seyfert Galaxy, V. C. Rubin, N. Thonnard, and W. K. Ford, Jr., Astrophys. J., 199, 31, 1975.

-

Evidence for Contraction in the Nuclear Ring of Barred Spiral Galaxy NGC 3351, V. C. Rubin, W. K. Ford, Jr., and C. J. Peterson, Astrophys. J., 199, 39, 1975.

-

Institutional Arrangements for the Space Telescope, V. C. Rubin plus 16 other authors, National Academy of Sciences, 1976.

-

Motions of the Excited Gas in the Barred Spiral Galaxy NGC 3351, C. J. Peterson, V. C. Rubin, W. K. Ford, Jr., and N. Thonnard, Astrophys. J., 208, 662, 1976.

-

Motion of the Galaxy and the Local Group Determined from the Velocity

-

Anisotropy of Distant ScI Galaxies I. The Data, V. C. Rubin, W. K. Ford, Jr., N. Thonnard, M. S. Roberts, and J. A. Graham, Astron. J., 81, 687, 1976.

-

Motion of the Galaxy and the Local Group of Galaxies Determined from the Velocity Anisotropy of Distant ScI Galaxies II. The analysis for the Motion, V. C. Rubin, W. K. Ford, Jr., N. Thonnard, and M. S. Roberts, Astron. J., 81, 719, 1976.

-

Spectra of Three Type I Supernovae, G. E. Assousa, C. J. Peterson, V. C. Rubin, and W. K. Ford, Jr., Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac., 88, 828, 1976.

-

New Observations of the NGC 1275 Phenomenon, V. C. Rubin, W. K. Ford, Jr., and J. H. Oort, Astrophys. J., 211, 697, 1977.

-

Position Angle of the Major Axis of the Nuclear Region of M31, C. J. Peterson, W. K. Ford, Jr., and V. C. Rubin, Astron. J., 82, 32-34, 1977.

-

The Scatter on the Hubble Diagram and the Motion of the Local Group, V. C. Rubin, Astrophys. J. Letters, 211, L1, 1977.

-

The Anisotropy of ScI Galaxy Velocities Interpreted as a Motion of our Galaxy and the Local Group of Galaxies, V. C. Rubin, Royal Greenwich Obs. Bull., 182, 183, 1976.

-

Is There Evidence for Anisotropy in the Expansion of the Universe?, V. C. Rubin, in I.A.U. Coll. #37, Decalages Vers le Rouge et Expansion de L'Univers, CNRS, Paris, 1977.

-

Is There Evidence for Anisotropy in the Hubble Expansion?, V. C. Rubin, Eighth Texas Symposium on Relativistic Astrophysics, M. D. Papagiannis, ed., Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 302, 408-421, 1977. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1977.tb37062.x.

-

The Velocity Field of the Barred Spiral Galaxy NGC 5383, C. J. Peterson, V. C. Rubin, and W. K. Ford, Jr., Astrophys. J., 219, 31, 1978.

-

Extended Rotation Curves of High Luminosity Spiral Galaxies: I. The Angle Between Axis of the Nucleus and the Outer Disk of NGC 3672, V. C. Rubin, N. Thonnard, and W. K. Ford, Jr., Astrophys. J. Lett., 1977.

-

The Compact Blue-shifted Galaxy RMB 56 (1216+141), T. D. Kinman, V. C. Rubin, W. K. Ford, Jr., and C. J. Peterson, Astrophys. J., 82, 879, 1977.

-

A New Mapping of the Velocity Field of NGC 1275, V. C. Rubin, W. K. Ford, Jr., C. J. Peterson, and C. R. Lynds, Astrophys. J. Suppl., 37, 235, 1978.

-

Extended Rotation Curves of High Luminosity Spiral Galaxies. II. The Anemic Spiral Galaxy NGC 4378, V. C. Rubin, W. K. Ford, Jr., K. M. Strom, S. E. Strom, and W. Romanishin, Astrophys. J., 244, 782, 1978.

-

NGC 5506: An X-ray Seyfert Galaxy, V. C. Rubin, Astrophys. J. Lett., 224, L55, 1978.

-

Extended Rotation Curves of High-Luminosity Spiral Galaxies, III. NGC 7212, C. J. Peterson, V. C. Rubin, W. K. Ford, Jr., and M. S. Roberts, Astrophys. J., 266, 770, 1978.

-

Extended Rotation Curves of High-Luminosity Spiral Galaxies, IV. Systematic Dynamical Properties Sa-Sc, V. C. Rubin, W. K. Ford, Jr., and N. Thonnard, Astrophys. J. Lett., 225, L107, 1978.

-

Radial Velocities of Spiral Galaxies Determined from 21-cm Hydrogen Observations, N. Thonnard, V. C. Rubin, W. K. Ford, Jr., M. S. Roberts, Astron. J., 83, 1564, 1978.

-

Redshifts, in Trans. of the Intern. Astron. Union, Reports of Astronomy, Pt. 3, XVIIA, pp. 211-220, W. B. Burton, ed., D. Reidel Publ. Co., Dortrecht, Holland, 1979.

-

Rotation Curves of High Luminosity Spiral Galaxies and the Rotation Curve of Our Galaxy, V. C. Rubin, I.A.U. Symposium #84, The Large Scale Characteristics of the Galaxy, D. Reidel Publ. Co., Dortrecht, Holland, p. 211, 1979.

-

Extended Optical Rotation Curves of Spiral Galaxies, Comments on Astrophysics, 8, 79, 1979.

-

Extended Rotation Curves of High-Luminosity Spiral Galaxies, V. NGC 1961, The Most Massive Spiral Known, V. C. Rubin, W. K. Ford, Jr., and M. S. Roberts, Astrophys. J., 230, 35, 1979.

-

Galactic Dynamics, Berkhuijsen, E. M., Einasto, J., V. Rubin, Science, 203, 43, 1979. [Book Reviews: Structure and Properties of Nearby Galaxies. Papers from a symposium, Bad Munstereifel, Germany, Aug. 1977, The Large Scale Structure of the Universe. Papers from a symposium, Tallinn, Estonia, USSR, Sept. 1977.]

-

Rotational Properties of 21 Sc Galaxies with a Large Range of Luminosities and Radii, from NGC 4605 (R = 4 kpc) to UGC 2885 (R = 122 kpc), V. C. Rubin, W. K. Ford, Jr., and N. Thonnard, Astrophys. J., 238, 471, 1980. [This paper ranked first as the most cited paper of all those based on observations with the 4 large US telescopes, 1980-1981, H. Abt, Publ. Ast. Soc. Pac., 87, 1050, 1985.]

-

Velocities and Mass Distribution in the Barred Spiral NGC 5728, V. C. Rubin, Astrophys. J., 238, 808, 1980.

-

Book Review – The Sky Explored – Celestial Cartography – 1500-1800, D. J. Warner and V. Rubin, Science, 210, 633, 1980.

-

Rotation and Mass of the Inner 5 Kiloparsecs of the SO Galaxy, NGC 3115, V. C. Rubin, C. J. Peterson, and W. K. Ford, Jr., Astrophys. J., 239, 50, 1980.

-

UGC 2885, The Largest Known Spiral, V. C. Rubin, MERCURY, Astron. Soc. Pacific, 9, 78, 1980.

-

Stars, Galaxies, Cosmos: The Past Decade, The Next Decade, V. C. Rubin, Science, 209, 64, 1980, reprinted in The Science Centennial Review, P. H. Abelson, and R. Kulstad, eds., A.A.A.S., Washington, D.C., 1980.

-

Galactic Go-around, V. C. Rubin, Natural History, 89, 80, August 1980.

-

Kinematics of Nuclei of Galaxies, V. C. Rubin, in Highlights of Astronomy, Vol. 5, p. 191, Reidel Publ. Co., Dortrecht, Holland, 1980.

-

A New Relation for Estimating the Intrinsic Luminosities of Spiral Galaxies, V. C. Rubin, D. Burstein, and N. Thonnard, Astrophys. J. Letter, 242, L149, 1980.

-

E. Margaret Burbidge, President Elect, V. C. Rubin, Science, 211, 915, 1981.

-

Comparative Dynamics of Sa, Sb, and Sc Galaxies, V. C. Rubin, in The Comparative HI Content of Normal Galaxies (proceedings of workshop, April 5-8, 1982) pp. 42-45, National Radio Astronomy Observatory, Green Bank, West Virginia, 1982.

-

NGC 3067: Additional Evidence for Nonluminous Matter?, V. C. Rubin, N. Thonnard, and W. K. Ford, Jr., Astron. J., 87, 477, 1982.

-

Redshifts, in Reports on Astronomy 1982, (XVIIIth General Assembly of the IAU, Patras, Greece), pp. 322-326, Patrick A. Wayman, ed., D. Reidel Publ. Co., Dordrecht, Holland, 1982.

-

The Distribution of Mass in Sc Galaxies, D. Burstein, V. C. Rubin, N. Thonnard, and W. K. Ford, Jr., Astrophys. J., 253, 70, 1982.

-

Rotational Properties of 23 Sb Galaxies, V. C. Rubin, W. K. Ford, Jr., N. Thonnard and D. Burstein, Astrophys. J., 261, 439, 1982.

-

Male World of Physics?, V. C. Rubin, Physics Today (Letters), 35, 121, 1982.

-

Priest Identified, V. C. Rubin, Physics Today (Letters), 35, 109, 1982.

-

Book Review: A Revised Shapley-Ames Catalog of Bright Galaxies, A. Sandage, G. A. Tammann, and V. C. Rubin, Sky and Telescope, 63, 478, 1982.

-

Dark Matter in Spiral Galaxies, V. C. Rubin, Sci. Amer., 248, 96, 1983, reprinted in The Universe of Galaxies, P. W. Hodge, ed., Freeman, New York, 1984.

-

NGC 3200: Is This What Our Galaxy is Like?, V. C. Rubin, in Kinematics, Dynamics and Structure of the Milky Way, pp. 379-384, W. L. H. Shuter, ed., Reidel Publ. Co., Dordrecht, Holland, 1983. [Proceedings of the Workshop on the Milky Way, Vancouver, British Columbia, 1982.]

-

The Rotation of Spiral Galaxies, V. C. Rubin, Science, 220, 1339, 1983.

-

Systematics of HII Rotation Curves, V. C. Rubin, in Internal Kinematics and Dynamics of Galaxies, (IAU Symp. 100, Besancon, France, August 9-13, 1982)g, pp. 3-10, E. Athanassoula, ed., D. Reidel Publ. Co., Dordrecht, Holland, 1983.

-

The Noninteracting Spiral Pair, NGC 450/UGC 807, V. C. Rubin and W. K. Ford, Jr., Astrophys. J., 271, 556, 1983.

-

A New Method for Evaluating the Hubble Constant, V. C. Rubin and N. Thonnard, in Highlights of Astronomy, Vol.6, p. 288, Richard M. West, ed., D. Reidel Publ. Co., Dordrecht, Holland, 1983.

-

Hubble-type Dependence in the Tully-Fisher Relationship, N. Thonnard and V. C. Rubin, in Highlights of Astronomy, Vol. 6, p. 287, Richard M. West, ed., D. Reidel Publ. Co., Dortrecht, Holland, 1983.

-

Colliding and Merging Galaxies. II. SO Galaxies with Polar Rings, F. Schweizer, B. C. Whitmore, and V. C. Rubin, Astron. J., 88, 909, 1983.

-

-

-

Luminosity-Dependent Line Ratios in Disks of Spiral Galaxies, V. C. Rubin, W. K. Ford, Jr., and B. C. Whitmore, Astrophys. J., 281, L21, 1984.

-

Stellar and Gas Kinematics in Disk Galaxies, B. C. Whitmore, V. C. Rubin, and W. K. Ford, Jr., Astrophys. J., 287, 66, 1984.

-

Evidence for Dark Halos Around Spiral Galaxies, V. C. Rubin, in The Proceedings of the First ESO-CERN Symposium, (Geneva, November 21-25, 1983), G. Setti and L. Van Hove, eds., pp. 204-205, ESO and CERN, Geneva, Switzerland, 1984.

-

Galaxy Formation and Cosmology – Short Contributions, V. C. Rubin. Proceedings of the 1st ESO/CERN Symposium held 21-25 November 1983 at CERN, Geneva, G. Setti and L. Van Hove, eds. Garching: European Southern Observatory (ESO), 1984, p. 204.

-

Rotation Velocities of 16 Sa Galaxies and a Comparison of Sa, Sb and Sc Rotation Properties, V. C. Rubin, D. Burstein, W. K. Ford, Jr., and N. Thonnard, Astrophys. J., 289, 81, 1985.

-

The Distribution of Mass in Spiral Galaxies, D. Burstein and V. C. Rubin, Astrophys. J., 297, 423, 1985.

-

A Convergence of Lives, Sofia Kovalevskaia: Scientist, Writer, Revolutionary. A book essay, V. C. Rubin and L. L. Stryker, The Mathematical Intelligencer, 7, No. 4, 69, 1985.

-

Report of IAU Commission 28: Galaxies, V. C. Rubin, Trans. Int. Astron. Union (Reports on Astronomy), 19A, 313-352, 1985.

-

The Hubble Expansion and the Motion of the Galaxy, V. C. Rubin, in Gamow Cosmology, "Enrico Fermi," F. Melchiorri and R. Ruffini, eds., pp. 160-167, North-Holland Physics Publ., The Netherlands, 1986.

-

Spiral Galaxy Dynamics and the Mass of the Universe, V. C. Rubin, in Gamow Cosmology, "Enrico Fermi", F. Melchiorri and R. Ruffini, eds., pp. 148-159, North-Holland Physics Publ., The Netherlands, 1986.

-

Is the Distribution of Mass within Spiral Galaxies a Function of Galaxy Environment?, D. Burstein, V. C. Rubin, W. K. Ford, Jr., and B. C. Whitmore, Astrophys. J., 305, L11, 1986.

-

GC 12591: The Most Rapidly Rotating Disk Galaxy, R. Giovanelli, M. P. Haynes, V. C. Rubin, and W. K. Ford, Jr., Astrophys. J., 301, L7, 1986.

-

Optical Rotation Velocities and Images of the Spiral Galaxy NGC 3198, D. A. Hunter, V. C. Rubin, and J. S. Gallagher III, Astron. J., 1, 1086, 1986.

-

Dark Matter in the Universe, in Highlights of Astronomy, V. C. Rubin, Vol. 19, J. P. Swings, ed., pp. 27-38, D. Reidel Publ. Co., Dordrecht, Holland, 1986.

-

What's the Matter in Spiral Galaxies?, V. C. Rubin in Highlights of Modern Astrophysics: Concepts and Controversies, (symposium held in honor of Ed Salpeter), S. L. Shapiro and S. A. Teukolsky, eds., John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N. Y., pp. 269-297, 1986.

-

Women's Work: for Women in Science, a Fair Shake is Still Elusive, V. C. Rubin, Science, 86, 7, 58, 1986.

-

On the Ratio [NII]/Ha in the Nucleus of M33 and in the Nuclei of other Galaxies, V. C.

-

Rubin, and W. K. Ford, Jr., Astrophys. J. Letters, 305, pp. L35, 1986.

-

Evidence for a Central Massive Component in Late Type Spirals, V. C. Rubin, and J. A. Graham, Astrophys. J. Letters, 316, L67, 1987.

-

Difference in Mass Distribution for Field and Cluster Spiral Galaxies, D. D. Burstein and V. C. Rubin, in Dark Matter in the Universe, J. Knapp and J. Kormendy, eds., D. Reidel Publ. Co., Dordrecht, Holland, 66, 1987.

-

Constraints on the Dark Matter from Optical Rotation Curves, V. C. Rubin, D. Reidel Publ. Co., Dordrecht, Holland, 51-65, 1987.

-

Distribution of Dark Matter in Polar-ring Galaxies, B. C. Whitmore, D. B. McElroy, F. Schweizer and V. C. Rubin in Dark Matter in the Universe, J. Knapp and J. Kormendy, eds., D. Reidel Publ. Co., Dordrecht, Holland, 315, 1987.

-

Coherent Large-scale Motions from a New Sample of Spiral Galaxies, V. C. Rubin, in Large Scale Structure of the Universe, I.A.U. Symposium #130, 181, 1987.

-

Activity in Near Normal Galaxies, V. C. Rubin, in Observational Evidence of Activity in Galaxies, I.A.U. Symposium #121, 461, 1987.

-

Some Surprises in the Dynamics of M33 and M31, V. C. Rubin in The Outer Galaxy, L. Blitz and F. J. Lockman, eds., Springer-Verlag, New York, 247, 1988.

-

Dark Matter in the Universe, V. C. Rubin, Proc. American Phil. Soc. 132, 434--443, 1988.

-

To L. F. from V. C. R., in Philosophy, History and Social Action: Essays in Honor of Lewis Feuer, S. Hook, W. L. O'Neill, and R. O'Toole, eds., Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, Holland, p. 391, 1988.

-

The Morphology of the Ionized Gas in M31's Bulge, R. Ciardullo, V. C. Rubin, G. H. Jacoby, H. C. Ford, and W. K. Ford, Jr., Astron. J., 95, 438, 1988.

-

Molecular and Ionized Gas in the Peculiar Galaxy NGC 2146, J. S. Young, M. J. Claussen, S. G. Kleinmann, V. C. Rubin, and N. Scoville, Astrophys. J. Letters, 331, L81, 1988.

-

Rotation Curves for Spiral Galaxies in Clusters. I. Data, Global Properties, and a Comparison with Field Galaxies, V. C. Rubin, B. C. Whitmore, and W. Kent Ford, Jr., Astrophys. J., 333, 522, 1988.

-

II. Variations as a Function of Cluster Position, B. C. Whitmore, D. A. Forbes, and V. C. Rubin, Astrophys. J., 333, 542, 1988.

-

Large-Scale Motions in the Universe: A Vatican Study Week, V. C. Rubin and G. V. Coyne, S.J., eds., Princeton University Press, 1988.

-

Large-Scale Motions from a New Sample of Spiral Galaxies: Field and Cluster, V. C. Rubin, in Large-Scale Motions in the Universe, V. C. Rubin and G. V. Coyne, eds., Princeton University Press, pp. 187-196, 1988.

-

Field and Cluster Galaxies: Do they Differ Dynamically? V. C. Rubin, in Large-Scale Motions in the Universe, V. C. Rubin and G. V. Coyne, eds., Princeton University Press, pp. 541-558, 1988.

-

Cluster Credit: Who Seconded the Motion?, D. H. Gudehus and V. C. Rubin, Physics Today, 41, 150, 1988.

-

The First Spectrum of M31, V. C. Rubin, Sky and Telescope, 75, 350, 1988.

-

Women Astronomers in the USSR, V. C. Rubin, A. G. Massevitch, and A. K. Terentjeva, Bull. Am. Astron. Soc., 20, 984, 1988.

-

A Comparison of Optical and VLA Rotation Curves for Virgo Spirals, V. C. Rubin, J. D. Kenney, A. P. Boss, and W. K. Ford, Jr., Astron. J., 98, 1246-1252, 1989.

-

The Local Supercluster and Anisotropy of the Redshifts, V. C. Rubin, in The World of Galaxies: Proceedings of a Symposium Le Monde des Galaxies, in honor of Gerard and Antoinette de Vaucouleurs on the occasion of his seventieth birthday, H. G. Corwin, Jr. and L. Bottinelli, eds., pp. 431-452, Springer-Verlag New York, Inc., 1989.

-

The Local Supercluster, V. C. Rubin, in Gerard and Antoinette de Vaucouleurs: A Life for Astronomy, M. Capaccioli and H. Corwin, eds., pp. 215-236, World Scientific, Singapore, 1989.

-

Weighing the Universe: Dark Matter and Missing Mass, V. C. Rubin, in Bubbles, Voids, and Bumps in Time, J. Cornell, ed., pp. 73-104, Cambridge University Press, Princeton, N.J., 1989.

-

Evidence for a Triaxial Bulge in the Spiral Galaxy NGC 4845, F. Bertola, V. C. Rubin, and W. W. Zeilinger, Astrophys. J. (Lett.), 345, L29-32, 1989.

-

The Triaxial Bulge in NGC 4845 as indicated by the Velocity Field and Isophotal Twisting, F. Bertola, V. C. Rubin, and W. W. Zeilinger, in ESO/CTIO Workshop on Bulges of Galaxies, eds. B. J. Jarvis and D. M. Terndrup, pp. 281-284, ESO, Munich, 1989.

-

Morphology and Dynamics of Galaxies in the Hickson Compact Groups, V. C. Rubin, W. K. Ford, Jr., and D. Hunter, in Evolution of the Universe of Galaxies, R. G. Kron, ed., pp. 30-32, Astronomical Society of the Pacific, San Francisco, 1990.

-

High Velocity Gas Drizzle into the Disk of NGC 4258, V. C. Rubin, and J. A. Graham, Astrophys. J. (Lett.), 362, L5-L8, 1990.

-

One Galaxy from Several: The Hickson Compact Group H31, V. C. Rubin, D. A. Hunter, and W. K. Ford, Jr., Astrophys. J., 365, 86-92, 1990.

-

Memories of the First Texas Symposium, E. A. Spiegel, V. C. Rubin, and J. L. Greenstein, Physics Today, 43, 118, 1990.

-

Optical Properties and Dynamics of Galaxies in the Hickson Compact Groups, V. C. Rubin, D. A. Hunter, and W. K. Ford, Jr., Astrophys. J. Supp., 76, 153-183, 1991.

-

Evidence for Dark Matter from Rotation Curves: Ten Years Later, V. C. Rubin, in After the First Three Minutes, AIP Conf. Proc. 22, eds. S. S. Holt, C. L. Bennett, and V. Trimble, 371, 1991.

-

Two Generations of Astrophysicists Look at the Problem of Opening the Doors for Women In Science, V. C. Rubin, in Recruiting and Retaining Women in Physics, Extracted in Physics Today, 45, 38, Aug. 1992.

-

Virgo Cluster Galaxies with Rapidly Rotating Disks, V. C. Rubin and J. D. P. Kenney, Bull. Am. Astron. Soc., 23, 1339, (Abstract), 1992.

-

Cospatial Counterrotating Stellar Disks in the Virgo E7/S0 Galaxy NGC 4550, V. C. Rubin, J. A. Graham, and J. P. D. Kenney, Astrophys. J. (Lett.), 394, L9-L12, 1992.

-

Herbig-Haro Objects in the Receding Lobe of the L1550 Outflow, J. A. Graham and V. C. Rubin, Publ. Astron. Soc. Pacific, 104, 104, 1992.

-

Women in Astronomy: A Sampler of Issues and Ideas, N. Barlow, F. A. Cordova, J. Bahcall, J. Price, K. Eastwood, N. Bahcall, G. Clayton, J. Lutz, J. Bell Burnell, D. Hunter, and 6 coauthors, Mercury, 21, 27-36, 1992.

-

Galaxy Dynamics and the Mass Density of the Universe, in Physical Cosmology, ed. D. Schramm, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci., 90, 4814, 1993.

-

NGC 4550: A Two-Way Galaxy, V. C. Rubin, Mercury, XXII, 109, 1993.

-

First Person Astronomy – NGC 4550 – A Two-way Galaxy, V. C. Rubin, Astr. Soc. Pacific. Mercury, 22, 109, 1993.

-

Kinematics of NGC 4826: A Sleeping Beauty Galaxy, not An Evil Eye, V. C. Rubin, Astron. J., 107, 173, 1994.

-

Multi-Spin Galaxies, V. C. Rubin, Astron. J., 108, 456, 1994.

-

Reminiscences: Observing at the National Facilities, in A Look at AURA, 1994.

-

Gas Filaments in the Collisional Debris of NGC 4438, J.D.P. Kenney, V. C. Rubin, P. Planesas, and J. S. Young, Astrophys. J., 438, 135, 1995.

-

A Century of Galaxy Spectroscopy, V. C. Rubin, Astrophys. J., 451, 419, 1995.

-

Heldere sterrenstelsels en donkere materie (in Dutch), Zenit, Sept. 366, 1995.

-

Near-Nuclear Velocities in NGC 5907: Observations and Mass Models, B. W. Miller and V. C. Rubin, Astron, J., 110, 2692, 1995.

-

Kinematic Data for O-B5 Stars (Rubin +, 1962), V. C. Rubin, J. Burley, A. Kiasatpoor, B.Kock, G. Pease, E. Rutschedit, C. Smith, VizieR On-line Data Catalog: V/31A. Originally published in 1962 Astron. J., 67, 491,1995.

-

Evidence for a Merger in the Peculiar Virgo Cluster Sa Galaxy NGC 4424. J.D.P. Kenney, R. A. Koopmann, V. C. Rubin, and J. S. Young, Astron. J., 111, 152, 1996.

-

The Celestial Map, V. C. Rubin, for permanent display at the Einstein Statue, National Academy of Sciences, Washington D.C., April 1996.

-

Rubin, V. C., Happy Birthday Donald: Remarks After Dinner, in Gravitational Dynamics, ed. O. Lahav, E. Terlevich, and R. J. Terlevich (Cambridge University Press), 245, 1996.

-

Bright Galaxies, Dark Matters (a book), V. C. Rubin, Masters of Modern Physics Series, Springer-Verlag/AIP Press, New York, 1997.

-

Book Review: Bright Galaxies, Dark Matters/AIP, 1997, V. C. Rubin, The Observatory, 117, 311, 1997.

-

Rapidly Rotating Central Gas Disks in Virgo Disk Galaxies, V. C. Rubin, J.D.P. Kenney, and J. S. Young, Astron. J., 113, 1250, 1997.

-

From an Observer, V. C. Rubin, in Critical Dialogues in Cosmology, Proceedings of a Conference held at Princeton, New Jersey, 24-27 June 1996, Singapore: World Scientific, edited by Neil Turok, 597, 1997.

-

One Hundred Years of Galaxy Spectroscopy: On the Acceptance of the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society, The Observatory, 1997.

-

Eulogy: Robert Herman, Modern Astronomy, 1, 21, 1997.

-

What George Gamow Did Not Know About the Universe, in George Gamow Symposium, ed. E. Harper, D. Parke, D. Anderson, Conference Series 129, Astron. Soc. of the Pacific, San Francisco, 95, 1997.

-

Panel Discussion and Reminiscences of George Gamow, I. Gamow, M. Nirenberg, J. Follin, V. Rubin, A. Rich, R. Alpher, R. Herman, P. Abelson, in George Gamow Symposium, ed. E. Harper, D. Parke, D. Anderson, Conference Series 129, Astron. Soc. of the Pacific, San Francisco, 127, 1997.

-

Rotation Velocities of 90 Virgo Disk Galaxies, V. C. Rubin, A. H. Waterman, J. D. P. Kenney, American Astronomical Society, 191st AAS Meeting, Bull. Am. Astron. Soc., 29, 1379, 1997.

-

Dark Matter in the Universe, Scientific American Presents (special quarterly issue: Magnificent Cosmos) 9, 106, 1998.

-

Recollections after Fifty Years: Haverford AAS Meeting, December 1950, in The American Astronomical Society's First Century, ed. D. DeVorkin, V. C. Rubin, (AIP Press), pp. 90-93, 1999.

-

Kinematic Disturbances in Optical Rotation Curves among 89 Virgo Disk Galaxies, V. C. Rubin, A. W. Waterman, and J. P. D. Kenney, Astronom. J., 118, 236-260, 1999.

-

The Trials and Triumphs of American Women in Science, AWIS Magazine (Association for Women in Science) 28 (no. 2), 34-36, 1999.

-

Commentary on "A Correlation Between the Spectroscopic and Dynamical Characteristics of the Late F- and Early G-Type Stars" by Nancy G. Roman, Astrophys. J., 112, 554, 1950, V. C. Rubin, Astrophys. J., 525 (Centennial Issue) 401, 1999.

-

Roman’s Correlation Between Spectra and Motions of Intermediate-Type Stars, V. C. Rubin, Astrophys. J., Centennial Issue, 525C, 401, 1999.

-

One Hundred Years of Rotating Galaxies, V. C. Rubin, Publ. Ast. Soc. Pacific, 112, 747, 2000.

-

What We Cannot See and Yet Know Must Be There, V. C. Rubin, reprinted from Scientific American Presents, (Special Quarterly Issue: Magnificent Cosmos), in The Book of the Cosmos: Imagining the Universe from Heraclitus to Hawking, D. R. Danielson, ed., Helix Books/Perseus Publishing, Cambridge, Mass. 2000.

-

Imaging the Universe, V. C. Rubin, in Pontifical Academy of Sciences Proceedings, Nov. 2000.

-

Disturbed Kinematics in Virgo Cluster Spirals, V. C. Rubin, and J. Haltiwanger, in Disk Galaxies and Galaxy Disks, ed. J. G. Funes, S.J. and E. M. Corsini 2001, ASP Conference Series, 230, 421, 2001.

-

Rotation Curves of Spiral Galaxies, Y. Sofue and V. C. Rubin, Annual Review of Astron. and Astrophys., 39, 137, 2001.

-

Mass Density Profiles of Low Surface Brightness Galaxies, W. J. G. de Blok, S. McGaugh, A. Bosma, and V. C. Rubin, Astrophys. J. Letts., 552, L23, 2001.

-

High-Resolution Rotation Curves of Low Surface Brightness Galaxies: I. Data, S. McGaugh, V. C. Rubin, and W. J. G. de Blok, Astron. J., 122, 2381, 2001.

-

High-Resolution Rotation Curves of Low Surface Brightness Galaxies: II. Mass Models, W. J. G. de Blok, S. McGaugh, and V. C. Rubin, Astron. J., 122, 2396, 2001.

-

Why Study Nearby Galaxies?, V. C. Rubin, American Astronomical Society, 199th AAS Meeting, #02.01, Bull. Am. Astron. Soc., 33, 1303, 2001.

-

Why does an Optical Astronomer Study Something She Cannot See?, V. C. Rubin, in Beyond Earth: Mapping the Universe, D. DeVorkin, ed., pp. 186-203, National Geographic Society, Washington, DC, 2002.

-

The Stellar and Gas Kinematics of Several Irregular Galaxies, D. A. Hunter, V. C. Rubin, R. A. Swaters, L. S. Sparke, and S. E. Levine, Astrophys. J., 580, 194, 2002.

-

Stellar Motions in the Polar Ring Galaxy NGC 4650A, R. A. Swaters, and V. C. Rubin, Astrophys. J. (Lett.), 587, L23-L26, 2003.

-

A Brief History of Dark Matter, V. C. Rubin, in The Dark Universe: Matter, Energy, and Gravity, M. Livio, ed., pp. 1-13, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York, 2004.

-

Siting a Supernova, V. C. Rubin, Sky and Telescope, 108, 12, 2004.

-

The Stellar Velocity Dispersion in the Inner 1.3 Disk Scale-Lengths of the Irregular Galaxy NGC 4449, D. A. Hunter, V. C. Rubin, R. A. Swaters, L. S. Sparke, and S. E. Levine, Astrophys. J. 634, 281-286, 2005.

-

A Puzzling Polar-Ring Galaxy, V. C. Rubin, Sky & Telescope 109 (no. 5), 26-27, 2005.

-

"Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin," V. C. Rubin, in Out of the Shadows: Contributions of Twentieth-Century Women to Physics, N. Byers and G. Williams, eds., pp. 158-168, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2006.

-

Seeing Dark Matter in the Andromeda Galaxy, V. Rubin, Phys. Today 59 (no. 12), 8-9, 2006.

-

A Two-Way Galaxy, V. Rubin, Phys. Today 60 (no. 9), 8-9, 2007.

-

VLT/VIMOS Integral-Field Kinematics of the Giant Low Surface Brightness Galaxy ESO 323-G064, L. Coccato, R. Swaters, V. C. Rubin, S. D'Odorico, and S. McGaugh, in Formation and Evolution of Galaxy Disks, J. G. Funes and E. M. Corsini, eds., pp. 481-482, Astronomical Society of the Pacific, San Francisco, 2008.

-

VIMOS-VLT Integral Field Kinematics of the Giant Low Surface Brightness Galaxy ESO 323-G064, L. Coccato, R. A. Swaters, V. C. Rubin, S. D'Odorico and S. S. McGaugh, Astron. Astrophys., 490, 589-600, 2008.

-

Charlotte Moore Sitterly", V. C. Rubin, J. Astron. Hist. Heritage, 13, 145-148, 2010.

-

An interesting voyage, V. C. Rubin, Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys., 49, 1-28, 2011.

-

Star formation in two luminous spiral galaxies, D. A. Hunter, B. G. Elmegreen, V. C. Rubin, A. Ashburn, T. Wright, G. I. G. Józsa, and C. Struve , Astron. J., 146, 92, 2013.

Bright Galaxies, Dark Matter, and Beyond: The Life of Astronomer Vera Rubin

by Ashley Jean Yeager (MIT Press, 2021)

“How Vera Rubin convinced the scientific community that dark matter might exist, persevering despite early dismissals of her work and widespread sexism in science.” (From the publisher)

Carnegie Context? Vera Rubin was a Staff Scientist at what is today the Earth & Planets Laboratory for nearly 50 years. In the 1970s, with collaborator Kent Ford, she provided observational evidence for Dark Matter—the invisible material that makes up more than 80 percent of the mass of the universe. In 2019 the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile was named in her honor.

Vera Rubin: a Life

by Jacqueline Mitton and Simon Miton (Harvard University Press, 2021)

“The first biography of a pioneering scientist who made significant contributions to our understanding of dark matter and championed the advancement of women in science.” (From the publisher.)