Peng Ni is an experimental geochemist who joined the Earth and Planets Laboratory in 2017 as a Carnegie Postdoctoral Fellow. Working with Staff Scientist Anat Shahar, Ni blends experimental petrology, non-traditional isotope geochemistry, and natural sample studies to explore the isotope fractionation of copper (Cu) and iron (Fe).

In this Postdoc Spotlight, Ni discusses how he got interested in experimental geochemistry, his most recent publication, and his love of photography.

1) What is your area of research?

I see myself as an experimental geochemist. My research focuses on understanding the geological processes that occurred during the formation, differentiation, and evolution of Earth and other planetary bodies.

2) What are the broader implications of your work?

My work helps us understand the large-scale processes on Earth and other planetary bodies, which control the internal structure of a planet, the fate of its volatiles (like water and carbon), the evolution of an atmosphere, and ultimately whether it's capable of sustaining life.

3) Can you summarize your recent publication and why it is important?

My most recent publication solved a previous puzzle for iron meteorites, which are remnants of the cores of small planetary bodies in the early Solar System.

Previous studies found that iron meteorites are more enriched in heavy isotopes of Fe compared with the lighter Fe isotope composition of their parent bodies. This difference in iron meteorites’ isotopic fingerprint indicated a large-scale process that caused the Fe isotopic ratios to change at some point during planetary development. My work demonstrated with experiments and modeling that this fractionation occurred early in planetary development as the core crystallized in the parent bodies of iron meteorites.

It is important because it solves an existing problem in the area of iron meteorite study, and improves our understanding of planetary evolution in the early Solar System.

If you want to read more, here’s a link to the press release for this publication.

4) What inspired you to choose this field of study?

During my Ph.D., I had the opportunity to work on lunar samples returned by the Apollo mission. I was fascinated by these samples from another world and got highly interested in planetary science. While working on that project, I realized that we lack a fundamental understanding of many planetary processes, which need to be studied experimentally. Therefore, I devoted myself as an experimental geochemist to explore some of the exciting questions in this field, such as the fate of volatiles during Moon formation.

5) How has your background influenced your research?

The high school I attended was one of the best in China that highly emphasizes math and science. During high school, I trained for the National Chemistry Olympiad competition and was fortunate to get the first prize in 2007. The training included college-level theories and experiments in chemistry, which I found to be very interesting.

These experiences were essential for me to become a scientist later and for my choice of experimental geochemistry as the field of study.

6) What else has influenced your thinking as a scientist?

I’ve loved reading detective fiction since high school, which guided me to think in a very logical way.

To some extent, solving puzzling problems in the field of geochemistry is similar to the job as a detective. We identify problems, come up with hypotheses, and then look for evidence to test these hypotheses. I think solving these geochemical problems can be as satisfying as solving a crime case.

7) When you’re not actively researching, what hobbies or activities do you enjoy in your spare time?

When I am not actively doing research, I like going outside for photography. I picked up photography as a hobby several years ago and was soon fascinated by how photographers convey their vision of the world through photography. I am mostly interested in landscape photography and like shooting beautiful scenes near the area I live and the places I travel to. I also use photography as a way to record important moments with my family.

You can see some of my photos on my personal website: https://peng-ni.com/gallery/.

8) If you could meet one of your science heroes, who would it be?

It would be Clair Patterson. He developed the lead-lead dating method and was the first person that precisely dated the Earth to be 4.55 billion years old. This number has stayed largely unchanged since 1956 when he made the measurements. He is my science hero not only because of his work on precisely dating the Earth. While developing the lead-lead dating technique, he encountered lead contamination and realized that industrial lead was a growing problem for public health. His subsequent campaign against lead poisoning was seminal in banning tetraethyllead in gasoline and lead solder in food cans.

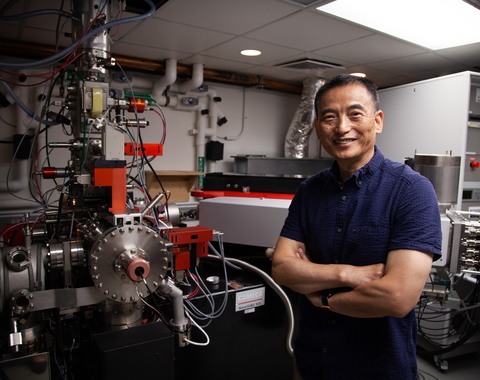

9) Why did you choose Carnegie’s Earth and Planets Laboratory?

The type of research I do requires a wide range of experimental and analytical techniques. Carnegie's Earth and Planets Laboratory is one of the few unique places with all the instrumentation and expertise I was looking for. I was also fortunate to get the prestigious Carnegie Postdoc Fellowship, so I immediately decided to join Carnegie. My postdoc experience here has been wonderful and I am very grateful that I made this decision.

10) Do you have any advice for current graduate students?

Don't be limited by the projects our advisors give us. Try to come up with projects that are in line with our own interests and accomplish them. Finding our true passion in the area is critical for the scientific career in the long run. It took me almost four years to find my passion during my Ph.D., but it was very satisfying when I was able to finish a project of my own.

11) Anything else you’d like to add?

I have a personal website, https://peng-ni.com/, where you can find more information about myself and my research.