Cataloging Reflections by Kit Whitten, Carnegie Observatories Library Intern

It is commonly believed that when looking for valuable treasure, the best place to look is the attic—after all, works by Caravaggio, Van Gogh, Rembrandt, and Jackson Pollack have been discovered in attics—but not everyone thinks to look in the basement. Yet institutions like Carnegie Observatories often keep the best stuff in the basement.

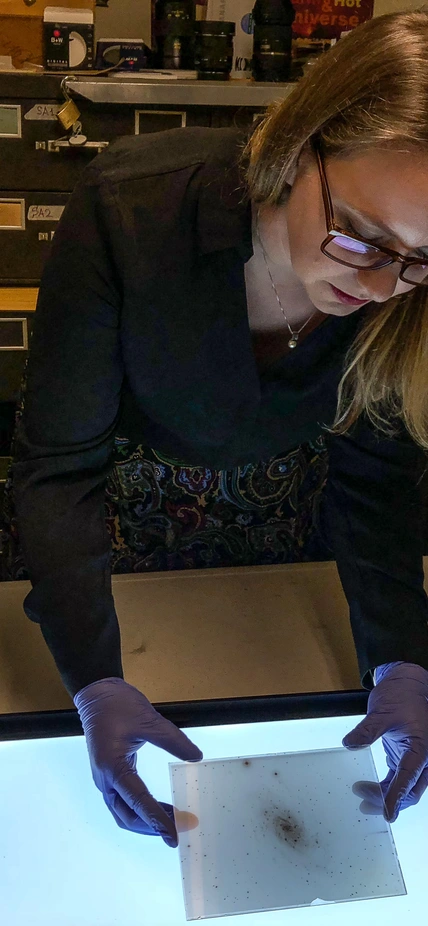

Inside the vault at the Observatories. Photo by Kit Whitten.

The underground vault at the Observatories houses the nation’s second-largest, single-institution collection of astronomical glass plates, which are thin sheets of glass with an emulsion image of celestial bodies. Photographic plates preceded plastic film as a medium in photography and were commonly used in astronomy from the 1850s through the 1990s. There are more than 250,000 glass plates in the Observatories’ vault. Scientists and astronomy enthusiasts alike can browse some of the Observatories’ collection by visiting the institution’s digital catalog, which enables researchers to survey a century’s worth of scientific data contained in 60,000 plates of night-sky objects. But the digital catalog doesn’t include quite all of the “direct image” plates of galaxies, star clusters, planets, moons, and more. Some of these plates, the Sandage collection, are still waiting to be discovered by a new generation of scientists.

Although I’m not a scientist, I have always loved looking at the stars and exploring the unknown. My name is Kit Whitten and I am a librarian and graduate student in USC’s Master of Management in Library and Information Science program. I dream of being the Indiana Jones of libraries—discovering lost treasures hiding in back rooms, attics, and even basements. My internship here at the Observatories has enabled my love of mysteries, since my duties center around a portion of the glass plate catalog that was only made available in 2011. This is the story of my work with Allan Sandage’s personal collection of astronomical glass plates and my efforts to make them more widely discoverable.

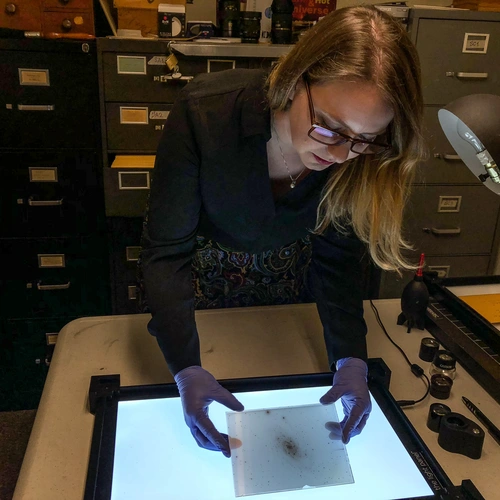

Kit Whitten in the plate analysis room. Photo by Cynthia Hunt.

Allan Sandage is well-known in the astronomy community, but as an outsider to the field, I had never heard of him before starting at the Observatories. According to Francois Schweizer, Staff Scientist Emeritus at the Carnegie Observatories, Sandage was known as the “heir of Edwin Hubble,” since he worked for Hubble as a student. Sandage was one of the first PhD students in the newly formed astronomy department at Caltech and he served as Hubble’s research assistant during his time there. After Hubble’s death in 1953, Sandage continued his mentor’s research program. Sandage is known for his work on the Hubble constant and the age of the universe, but had an incredibly broad scientific career that also included unraveling stellar evolution, the formation of galaxies, and the nature of quasars.

Allan Sandage, courtesy of Carnegie Institution for Science.

The reason Sandage’s collection contains so many mysteries is that it was unavailable to the wider community until after after his death. Much of what the collection contains remains unknown, thanks to an incident of timing—it came home months after the completion of the Observatories' most-recent cataloging project. It is understood at the Observatories that the plates kept in Sandage’s office were related to his research and/or his work on The Hubble Atlas of Galaxies (1961) and The Carnegie Atlas of Galaxies (1994). When working on these atlases, in addition to his own images, Sandage gathered plates from multiple other astronomers in order to find the best images of the galaxies he was documenting.

“When Sandage’s collection became available in 2010, it was very exciting because its plates were considered to be among the most-important plates in the institution -- the cream of the cream for astronomy plates -- and Sandage had, accordingly, been very protective of them.” - François Schweizer

Once the Sandage collection was available to researchers again, the Observatories began to pursue ways to make the plates as widely known as possible. That’s where I come in. Adding the Sandage collection to the Observatories’ digital catalog ensures that scholars will have access to these resources now and in the future. Further, preserving metadata (data relating to the plates themselves, not the data on the plate) from the plates and their envelope sleeves will enable researchers to discover information resources relevant to their work and conduct research across subjects. For example, early on I discovered a pair of plate sleeves with additional writing beyond the standard information categories (such as plate number and subject observed).

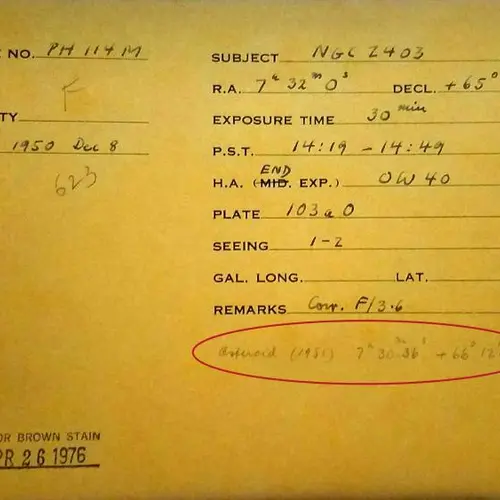

The first "asteroid" plate sleeve. Photo by Kit Whitten.

As it turns out, while studying the galaxy NGC 2403, astronomer Rudolph Minkowski noticed an asteroid that had been traveling across his field of view. Since he was not studying asteroids, Minkowski simply noted the location of the asteroid on the plate sleeves and continued his research on the galaxy. Sixty-eight years later, discovery of this writing led me to examine the plates themselves, on which I spied tiny arrows drawn in ink on each plate pointing to even tinier streaks across the sky that were captured in the image.

These streaks turned out to be the kind of asteroid studied by astronomer Joseph Masiero, a NASA JPL scientist and Deputy PI for NEOWISE. Masiero specializes in near-Earth objects, which are small Solar System bodies with orbits that bring them into proximity with Earth. The asteroid discovered on the plates in the Sandage collection was especially exciting to Masiero, because its appearance on multiple plates meant that its position and velocity could be measured and linked to an asteroid in existing catalogs of near-Earth objects. Using these measurements, Masiero discovered that the asteroid had been formally discovered in 1989, 30 years after the plates were obtained, meaning that these measurements could provide a dramatic improvement in our knowledge of this asteroid’s orbit.

“The plate archive at the Carnegie Observatories provides us the opportunity to search for detections of asteroids from before they were discovered. Though rare, these data can have dramatic effects on how well we know the orbits of these asteroids, and let us study how the orbit has changed over time. Historical data can enable studies that would require decades of waiting if started now." - Joseph Masiero

In information science (the realm of data management that includes libraries, archives, and museums), those who handle historically important objects must often balance preservation and restoration. On one hand, restoring an item to its original condition is desirable for academic study of the object. But on the other, if changes in its condition tell an interesting story, there is also value in preserving that “damage.” In the case of glass plates, there is some debate around whether or not ink markings on the plates (such as those that identified Minkowski’s asteroid discovery) should be removed as part of the cataloging and digitization process.

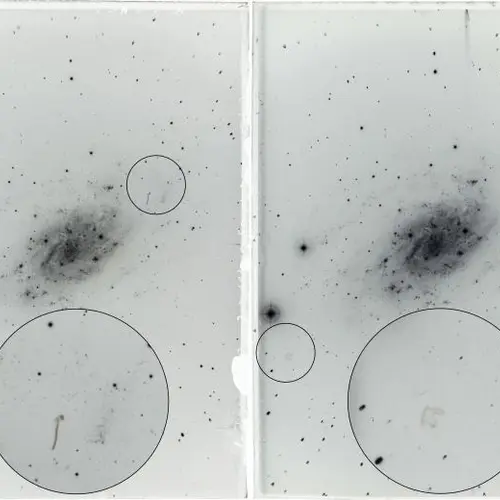

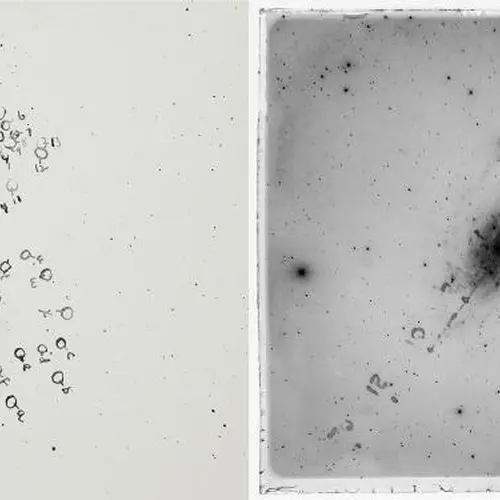

Inked plates. Images by Edwin Hubble and George Willis Ritchey

At the Observatories, emphasis is currently placed on preservation. After all, the Observatories is the home of the “VAR!” plate, which represents one of the largest discoveries in astronomy and is one of the most widely known examples of writing on a glass plate. In many cases, keeping the ink markings on plates records the scientific method used by astronomers to make the important discoveries that influence our current understanding of space. However, part of the luxury of being able to preserve the ink markings is that there has not yet been an instance at the Observatories where digital imaging has been requested for a plate with ink markings that interfere with scientific data.

At the DASCH project at Harvard, ink markings are removed prior to scanning in order to get the most accurate photometric data in their digital images. Photometry is the science of measuring light and can be used in astronomy to determine the distance of an illuminated celestial body, like a star or galaxy. By focusing on the scientific data contained in its plates, Harvard is enabling the historical measurement of objects in our night sky. While Harvard has decided to restore their plate collection in order to preserve scientific data, the Observatories has decided to keep the ink markings on their plates in order to preserve a scientific method.

Nova plate and closeup side by side. Image by Milton Humason

Keeping ink on the plates has already enabled serendipitous discoveries, such as the asteroid plates, bringing my dream of discovering lost treasures a reality. At the moment, while Masiero researches our re-discovered asteroid, we are researching the “Nova” plate shown above while I continue to catalog Sandage’s extensive collection. I’ve been told by an astronomer that it’s ambitious to try to record all the information contained in an astronomical plate collection, but I personally can’t wait to see what else is hiding in the Observatories’ basement.