Baltimore, MD— New work led by Carnegie’s Steven Farber, with help from Yixian Zheng’s lab, sheds light on how form follows function for intestinal cells responding to high-fat foods that are rich in cholesterol and triglycerides. Their findings are published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Enterocytes are specialized cells that line the insides of our intestines. The intestinal surface is like a toothbrush, with lots of grooves and protrusions that allow the cells there to grab and absorb nutrients from food as it is digested, including the lipid molecules from fatty foods. The cells absorb, process, and package these lipids for distribution throughout our bodies. Clearly they are very important for sustaining good health and keeping us alive, since lipids are necessary for many of the body’s functions, including nutrient absorption and hormone production.

“When we eat fatty foods, our body’s response is coordinated between our digestive organs, our nervous system, and the microbes living in our gut,” explained Farber. “Our research used zebrafish to focus on one aspect of this system—how the enterocyte cells inside our intestines respond to a high-fat meal.”

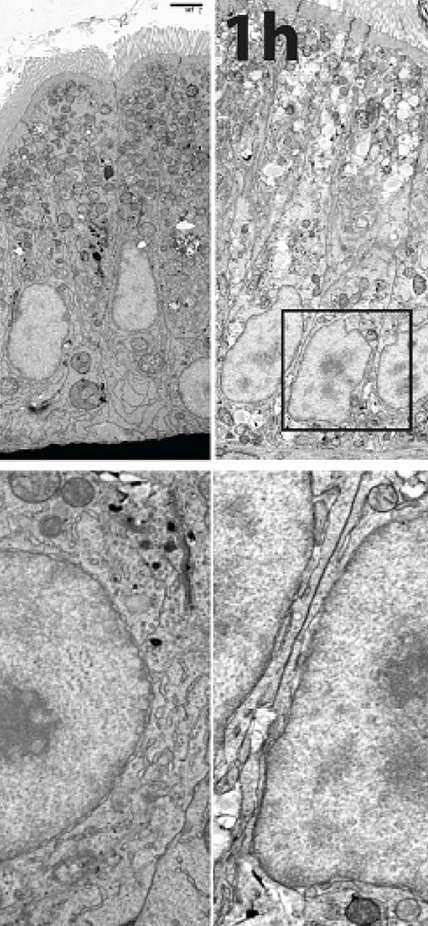

It turns out that fatty foods cause enterocyte cells to do some interior remodeling. Cells are like tiny factories, where different functions are carried out by highly specialized structures called organelles. In enterocytes, several of these organelles undergo changes in their shape in response to an influx of fats from rich foods. One such shape shift occurs in the nucleus, where the cell’s DNA is stored. Farber’s team demonstrated that the nucleus takes on a rapid and reversible ruffled appearance after fatty foods are consumed.

This is of interest because a cell’s genetic material is housed in the nucleus, and this is the location where different genes get turned on and off in response to external stimuli, such as the presence of lipids from fatty foods.

So the team examined this issue further and found that the shape shifting in the nucleus coincides with the activation of certain genes that regulate the intestinal cell’s ability to package and distribute the lipids to other parts of the body. The team was able to determine that this activation process occurs within an hour of eating high-fat foods.

“Our working hypothesis is that the whole response to fat in the enterocyte—the remodeling and gene activation—may be coordinated by an organelle called the endoplasmic reticulum,” said lead author Erin Zeituni.

If the cell is a factory, then the endoplasmic reticulum it is the assembly line, where various cellular products are synthesized, stored, and packaged for distribution outside of the cell. It is constructed of a series of interconnected tube-like shapes.

When the research team used pharmaceuticals to inhibit one function of the endoplasmic reticulum (the building of so-called lipoprotein particles that will export fats out of the cell), the gene activation process was inhibited for many key genes and nuclear ruffling was also altered. This demonstrated that the flux of fat in the endoplasmic reticulum is crucial for initiating the intestinal response to a fatty meal.

“So much of the process by which enterocytes prepare and package fats for distribution to the circulatory and lymphatic system is poorly understood,” Farber said. “These findings should help increase our understanding of the basic molecular and cellular biology of intestinal cells.”

This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney, National Institute of General Medicine, and the Zebrafish Functional Genomics Consortium.