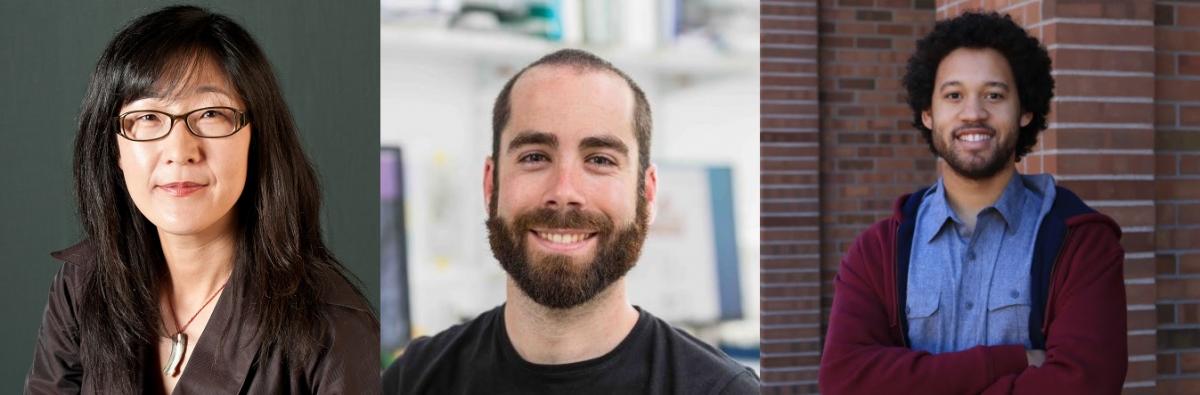

Palo Alto, CA— Carnegie’s Sue Rhee and Moises Exposito-Alonso are leading members of an initiative to identify genes related to stress tolerance in the mustard plant field pennycress. Theirs was one of seven biofuel research projects awarded a total of $68 million over five years by the Department of Energy.

Climate change is one of the greatest challenges facing humankind and scientists from a wide variety of fields are applying their expertise to help understand and mitigate its effects. This includes plant scientists, whose work can help maintain food security in a warming climate, sequester carbon pollution from the atmosphere, and develop renewable energy sources, such as biofuels.

But sustainable bioenergy programs will require plants that can grow in the margins of other agriculture—in the off season or on land that cannot support food crops. The seven newly funded DOE projects all support basic science research to identify genes that convey resilience and productivity in plants that can produce oil for biofuels including jet fuel.

“This research will help us understand the molecular mechanisms that lead to crops with greater productivity and survivability in stressful environments,” said Chris Fall, Director of DOE’s Office of Science.

Led by John Sedbrook at Illinois State University, with Exposito-Alonso and Rhee spearheading two of the project’s four aims—the pennycress team will probe the plant for genes that will enable it to be resilient in stressful conditions and to thrive in a variety of environments and agricultural systems.

A member of the mustard family, field pennycress is found throughout the world’s temperate climates and almost everywhere in the United States, from Florida to Alaska. In the Midwest and Pacific Northwest, it is being developed as a biofuel crop because its hardiness in extreme cold temperatures and rapid springtime growth mean it can share agricultural land with corn and soybeans during the off season. Some pennycress varieties can yield 65 gallons of oil per acre each year.

However, North American populations have limited genetic variation, which inhibits its ability to survive drought, heat waves, floods, and other environmental challenges related to climate change.

The awardees will use a combination of computational genomics and CRISPR technology to identify the genes responsible for pennycress’ evolutionary successes and look for those that could confer superior stress tolerance, as well as improve root architecture and the ability to obtain water and nutrients when they are scarce.

“In true Carnegie fashion, the effort will deploy a multi-disciplinary approach that combines biochemistry, evolutionary genetics, bioinformatics, agronomy, soil science, remote sensing, and more,” said Carnegie Plant Biology Acting Director Zhiyong Wang.

“To tackle this bioenergy and climate change adaptation challenge, we will start studying old field pennycress populations from Europe, where the species likely originated and natural genetic variation is high,” added Exposito-Alonso.

Once the genes for these desired traits are identified, field pennycress plants in the Corn Belt that have been engineered to express them could produce 3 billion gallons of oil for manufacturing biofuels and an additional 20 million tons of animal feed.

“When the world comes out of the current COVID-19 pandemic, we will have an opportunity to enhance our commitment to renewable energy sources, including biofuels,” Rhee said. “The mustard family, of which field pennycress is a member, contains several other biofuel crops, including rapeseed, canola, camelina, and carinata. This means that our findings could have even wider reaching impacts on bioenergy development.”

Added Jason Thomas, a postdoctoral scholar in Rhee’s lab and pennycress expert who co-developed the grant proposal and will be working on the project starting this fall: “I’m excited that so many new institutions have joined up to research field pennycress, making it much more likely that this plant will go out and make a difference in the world.”