Mineralogist and crystallographer Larry Finger, who spent more than three decades at Carnegie Science before retiring in 1999, passed away June 21 at his home in Smithville, Missouri. Working at Carnegie Science’s former Geophysical Laboratory, now part of the Earth and Planets Laboratory, he pioneered the invention and implementation of computer-driven automation of scientific instrumentation, profoundly influencing a generation of mineralogists and petrologists.

“It is rare in science for one individual to open pathways to discovery for so many others,” said Carnegie Science Staff Scientist Robert Hazen in a memorialization of Finger for American Mineralogist. “Larry Finger led the geoscience community in producing a flood of crystallographic and analytical data—contributions that continue to usher in a new age of geoinformatics.”

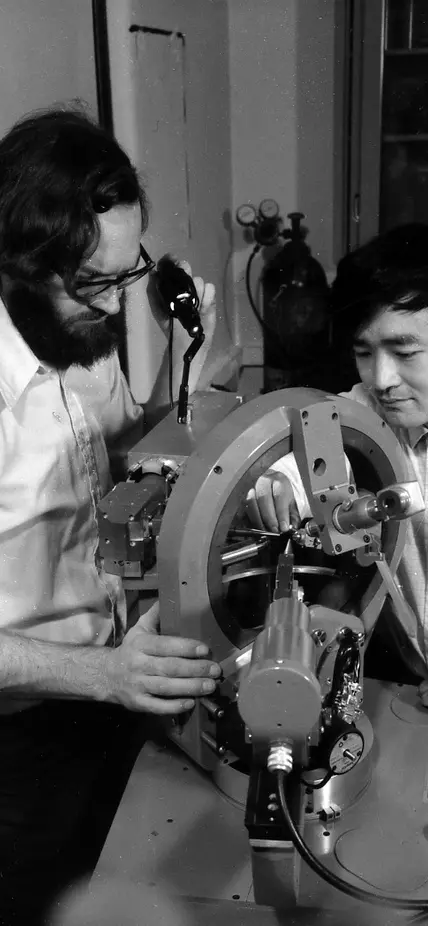

Having spent his childhood on farms in Iowa and Minnesota, Finger developed an early fascination for mechanical science that lasted throughout his life. That interest would inform his career and earn him acclaim when, in the early 1970s, Finger and Carnegie Science Electronics Engineer Christos Hadidiacos developed an automated X-ray diffractometer. In retrofitting diffractometers with computer-connected motors, Finger and Hadidiacos’ modification allowed scientists to collect the data necessary to determine a crystal’s structure in a fraction of the time previously required. In retirement, Finger would again leverage that fascination with, and knack for, computer science to refurbish computers for local students in need.

Finger earned his Ph.D. at the University of Minnesota, where he studied under noted mineralogist and crystallographer Tibor Zoltai. His research was influenced by the work of previous crystallographers, including Martin Buerger, who was a pioneer in the field and trained Zoltai at MIT.

During his time at Carnegie Science, Finger was a prolific publisher. In collaboration with Hazen, who first joined Carnegie Science as a postdoc in 1976, he published more than 100 papers, a book, and 27 articles for American Mineralogist over a 23-year period.

According to Hazen, Finger’s favorite publications involved extreme crystallographic challenges, including devising new methods of high-pressure crystallography; high-pressure, single-crystal studies of condensed hydrogen; determination of the complex structure of fingerite, the mineral named after him; and measuring X-ray diffraction from what was at the time the smallest crystal ever attempted.

After retiring from Carnegie Science, Finger and his wife, Denise, spent six years traveling the country. Eventually, they settled in Missouri to be close to their daughter Pam and her two children, Riggins and Cael. In addition to Denise, Pam, and his grandchildren, Larry is survived by another daughter, Cindi.

“Carnegie Science offers our condolences to Larry’s family, friends, and colleagues,” said Carnegie Science Earth & Planets Laboratory Director Michael Walter. “We are grateful for his three decades of dedication to the organization. He will be remembered for both his innumerable contributions to geoscience and for the generous spirit he shared with many across Carnegie Science.”