Stargazing is a fundamental human activity. Tracking the movement of celestial bodies across the night sky has shaped civilizations and informed religious beliefs, artistic expression, and scientific thinking for millennia.

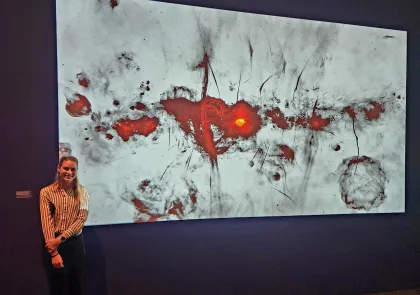

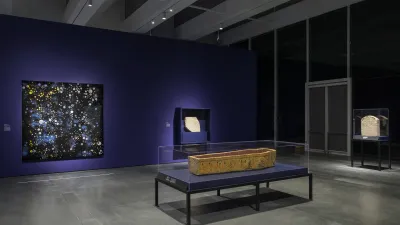

Exploring these intersections, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s Mapping the Infinite: Cosmologies Across Cultures spans centuries and probes the various relationships that roughly 15 different civilizations—from the Neolithic to the modern—developed with the universe. The exhibit, which opened in late October and runs through March 2, connects the observation and analysis of objects in space with broader ideas about the origins and structures of the universe, incorporating the realms of myth, philosophy, religion, and science.

Part of the Getty Foundation’s PST ART: Art & Science Collide initiative, Mapping the Infinite was curated in partnership with more than 40 different institutions, including Carnegie Science.

One of three Carnegie objects on display, Edwin Hubble’s famous VAR! plate is among the smallest works in the exhibition, LACMA’s Stephen Little said at the Mapping the Infinite unveiling event earlier this fall. But despite its diminutive size—roughly equivalent to a notecard—what it represents is cosmically large, enthused Little, who is the Florence and Harry Sloan Curator of Chinese Art and heads the museum’s Korean, and South & Southeast Asian art departments.

The plate shows an image taken by legendary Carnegie Science astronomer Edwin Hubble in 1923, which revealed the existence of the Andromeda galaxy beyond the boundaries of our own Milky Way. This breakthrough—made at Carnegie’s Mount Wilson Observatory in the San Gabriel Mountains overlooking Pasadena—transformed astronomy and advanced a new understanding of our place in the cosmos.

“This instantaneously took our universe from a small thing, by astronomical standards, to an immense thing,” explained Carnegie Science President John Mulchaey at the launch event in October.

LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director Michael Govan spoke about his and Little’s first visit to the Carnegie Science Observatories to see Hubble’s plate, describing the glass object as “nearly sacred in our own cosmologies.”

Along with Observatories Staff Scientist Juna Kollmeier and Strategic Initiatives Coordinator Erica Clark, Mulchaey worked closely with LACMA staff to bring the exhibition to fruition. All three are slated to participate in public programs related to the exhibition in the coming months.

Mapping the Infinite also includes a floor-to-ceiling projection of video of a survey of galaxies by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey’s fifth generation, of which Kollmeier serves as director, and an image of the Milky Way’s central region captured by a team of scientists including Carnegie Science postdoc Allison Matthews using the MeerKAT radio telescope in South Africa.

Beyond Carnegie Science’s contributions, LACMA’s exhibition features a wide range of priceless art and artifacts from ancient Mesopotamia, western Europe, East and South Asia, and the Americas, including the native Tongva and Chumash tribes who have long called Southern California home.

The oldest object is a stone cylinder seal that, when rolled on wax or clay, depicts the Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar. Other artifacts include a Roman statue of the Persian god Mithras, books by historical astronomers Nicolaus Copernicus and Abd al-Raḥmān ibn ʿUmar al-Ṣūfī’, and a hand-drawn portrait of Galileo Galilei, as well as contemporary artistic reflections on the universe, such as Helen Lundeberg’s Microcosm and Macrocosm.

Installation photograph, Mapping the Infinite: Cosmologies Across Cultures, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Oct 20, 2024–Mar 2, 2025, 2025, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Nebra Sky Disk, 1600 BCE (facsimile, 2002), Landesmuseum Für Vorgeschichte, State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology Saxony-Anhalt, Juraj Lipták, Photo © LDA Sachsen-Anhalt, Juraj Lipták

Installation photograph, Mapping the Infinite: Cosmologies Across Cultures, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Oct 20, 2024–Mar 2, 2025, 2025, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Bowl with Courtly and Astrological Motifs, Central or Northern Iran, late 12th–early 13th century, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, purchase, Rogers Fund, and gift of The Schiff Foundation, 1957, digital image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Open Access Program

Installation photograph, Mapping the Infinite: Cosmologies Across Cultures, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Oct 20, 2024–Mar 2, 2025, 2025, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Willem Janszoon Blaeu, Celestial Globe, c. 1630, Adler Planetarium

Installation photograph, Mapping the Infinite: Cosmologies Across Cultures, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Oct 20, 2024–Mar 2, 2025, 2025, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Muhammad ibn 'Abd al-'Aziz al Khama'iri, Astrolabe, 1226–27/624 A.H., Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Carolyn Merchant, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Installation photograph, Mapping the Infinite: Cosmologies Across Cultures, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Oct 20, 2024–Mar 2, 2025, 2025, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Nebra Sky Disk, 1600 BCE (facsimile, 2002), Landesmuseum Für Vorgeschichte, State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology Saxony-Anhalt, Juraj Lipták, Photo © LDA Sachsen-Anhalt, Juraj Lipták

Installation photograph, Mapping the Infinite: Cosmologies Across Cultures, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Oct 20, 2024–Mar 2, 2025, 2025, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Bowl with Courtly and Astrological Motifs, Central or Northern Iran, late 12th–early 13th century, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, purchase, Rogers Fund, and gift of The Schiff Foundation, 1957, digital image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Open Access Program

Installation photograph, Mapping the Infinite: Cosmologies Across Cultures, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Oct 20, 2024–Mar 2, 2025, 2025, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Willem Janszoon Blaeu, Celestial Globe, c. 1630, Adler Planetarium

Installation photograph, Mapping the Infinite: Cosmologies Across Cultures, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Oct 20, 2024–Mar 2, 2025, 2025, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Muhammad ibn 'Abd al-'Aziz al Khama'iri, Astrolabe, 1226–27/624 A.H., Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Carolyn Merchant, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Planning for Mapping the Infinite began in 2019, building on a narrower exhibition that Little curated more than 20 years ago at the Art Institute of Chicago. But the genesis of the project can be traced all the way back to Little’s undergraduate experience.

In the 1970s, the curator enrolled in Cornell University’s Carl-Sagan-headed astronomy program. At the time, he couldn’t have imagined that one day he’d blend his fascination with the universe and a passion for art. But a mid-degree pivot to majoring in art history kickstarted a decades-long intellectual journey that would lay the foundation for Mapping the Infinite. So, when the Getty announced the theme of this latest PST Art initiative, Little was ready to seize the moment.

“When the Getty announced this about five years ago, Michael and I thought, ‘this is the time to do a really ambitious show on the global history of cosmology using works of art’,” he said. “It’s usually art and architecture where cosmologies are sort of visually articulated beyond texts.”

The exhibition represents the first time the relationship between celestial objects and religious and political power has been probed by an art museum, incorporating works of art Little explained at the Mapping the Infinite unveiling event.

He went on to detail how the project posed the same questions across the cultures represented in the exhibition, including: what is the concept of time; how was the universe created; what is the structure of space; what is the relationship between the Earth and the sky; how are objects on the sky mapped; and how celestial events like comets, supernovae, and eclipses are perceived.

The exhibition is organized into geographic and chronological sections, weaving these foundational human questions together with the birth of modern cosmology, including contributions by Carnegie, the U.S. Naval Observatory, and the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

“We’re proud to be collaborators on this awe-inspiring exploration of the many intersecting ways that objects in the night sky have shaped societies around the world through the ages,” Mulchaey concluded. “The cosmos has captivated humans for as long as we have existed, and Carnegie Science researchers continue to push the boundaries of what’s possible when it comes to understanding the cosmos.”

From the founding of the Carnegie Science Observatories by scientific powerhouse and Pasadena legend George Ellery Hale—who built the largest telescope in the world four times over—to our researchers’ current work exploring the earliest generations of stars and galaxies, revealing the atmospheres of distant worlds, and probing the mysterious nature of dark matter—Carnegie astronomy exists at the forefront of discovery.

More information about Mapping the Infinite: Cosmologies Across Cultures and tickets to the exhibition can be found at lacma.org.