Washington, DC—New research led by Carnegie’s Hélène Le Mével reveals new details about the system of magma chambers under the Hunga volcano, both before and after its disastrous 2022 eruption. The team’s findings, published last week in Science Advances, demonstrate a new method for probing submarine volcanos for their potential to cause similar damage.

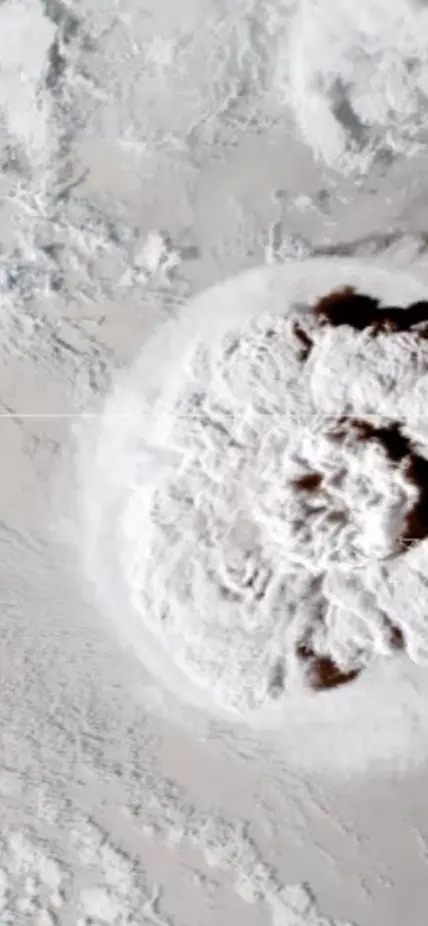

The eruption came at the end of a month-long period of volcanic unrest, following a seven-year hiatus for the volcano—devastating the Kingdom of Tonga islands and causing a global tsunami, an unprecedented amount of volcanic lightning, and perturbations in the upper atmosphere. . It was the largest explosive eruption recorded since Pinatubo in 1991.

“Although we have a wealth of data about the Hunga eruption’s effects both locally and globally, we know very little about its subsurface structure,” Le Mével explained.

The research team—which included Craig Miller of the Wairakei Research Center, Marta Ribó of Aukland University of Technology, Shane Cronin of University of Aukland, and Taaniela Kula of the Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources Nuku‘alofa, Tonga—set out to determine how much magma is stored under the Hunga volcano and how the eruption altered the magma system. This will help scientists understand the physical processes that shaped the 2022 eruption.

To answer these questions, the team used seabed-mapping technology to measure the depth to the seabed, or bathymetry, and gravity data taken by satellites to model the dynamics and architecture of the magma chambers under Hunga.

They found that the caldera floor collapsed by between 600 and 850 meters after the eruption, with up to 66 percent of the system’s magma exiting the volcano. However, a large amount of magma remains in two reservoirs suggesting a need for follow-up surveys on the volcano’s flanks. This information can help experts forecast the size and likelihood of future eruptions.

“More than three-quarters of Earth’s volcanism happens under the ocean, where continuous monitoring is very challenging” Le Mével explained. “Our findings demonstrate that the combination of satellite-derived marine gravity data and bathymetry mapping can uncover key characteristics of magma storage in submarine volcanic systems and identify those with the potential to produce eruptions of a similar scale to what happened at Hunga in 2022.”

Caption: This looping video shows an umbrella cloud generated by the underwater eruption of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano on Jan. 15, 2022. The GOES-17 satellite captured the series of images that also show crescent-shaped shock waves and lightning strikes. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens using GOES imagery courtesy of NOAA and NESDIS

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by New Zealand Ministry of Business, Innovation, and Employment’s Strategic Science Investment Fund and Beneath the Waves Endeavour Programme; the University of Auckland’s Faculty of Science Development Research Fund, and the Kingdom of Tonga’s Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources.