Q: To start out, can you give us a high-level overview of your research interests?

Vissapragada: I am interested in all things exoplanets. I think it's fair to say, in general, the sort of thing driving that interest is wanting to understand the typical outcomes of the planet formation process and, essentially, the life story of a typical planet. I’m interested in questions about size and shape and do they change over time. I want to know what influences the host star can have on a planet’s life. And what influences planets in a system have on each other.

Q: Are there specific aspects of the planetary lifecycle that are of particular interest to you?

Vissapragada: Since graduate school, I've been interested in atmospheric escape. This is related to planets that reside really close to their host stars and are being constantly irradiated. That radiation can cause some of the planet's atmosphere to literally boil away to space. Also, maybe the atmosphere that you see on a planet today isn't the atmosphere that it was born with. And I've always found that angle kind of compelling, because these are changing objects. And in a lot of cases, you can actually see them changing in real time, which I think is really pretty cool.

I've also been particularly interested in measuring the masses of intermediate sized planets. Between Jupiters, which are really big, and sub-Neptunes, which are pretty small and common, there are these uncommon weirdos in the exoplanet population. And I think there's growing evidence that some of them are likely to have had very exciting histories in terms of their evolutions. For example, some of them may have had very destructive evolutionary pathways. Like there are gas giants that started off with huge atmospheres and then something happens and all of it is lost and they’re left as a ball of rock that is much bigger than it should be.

Q: So, you like planets with dramatic life histories?

Vissapragada: Yes, I’m always a fan of drama.

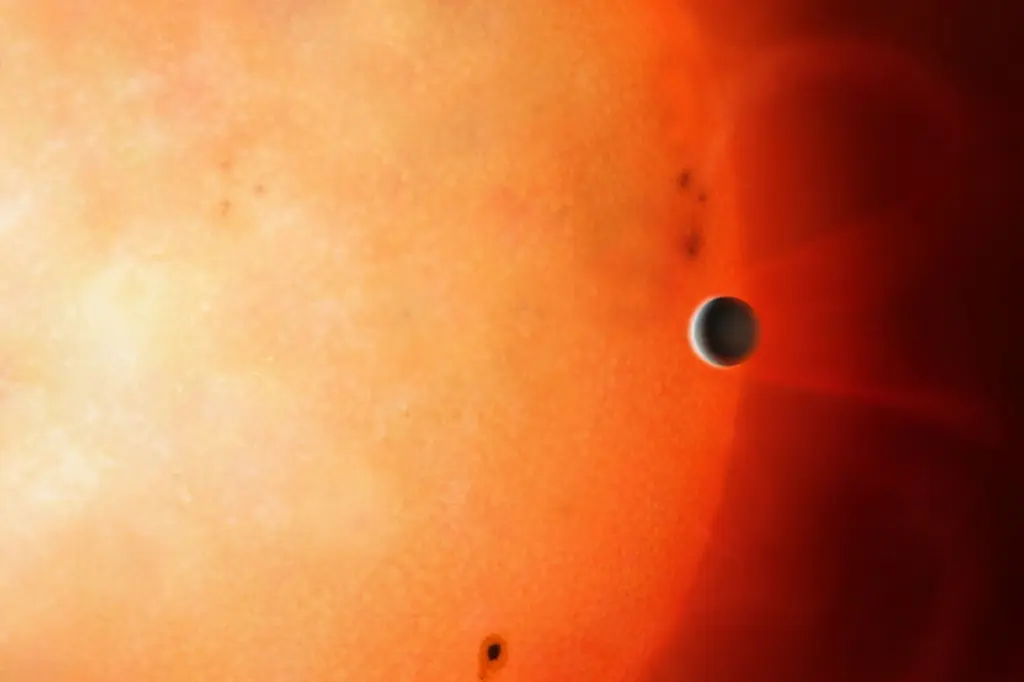

Artist's impression showing a Neptune-sized planet in the Neptunian Desert. It is extremely rare to find an object of this size and density so close to its star. Credit: University of Warwick/Mark Garlick

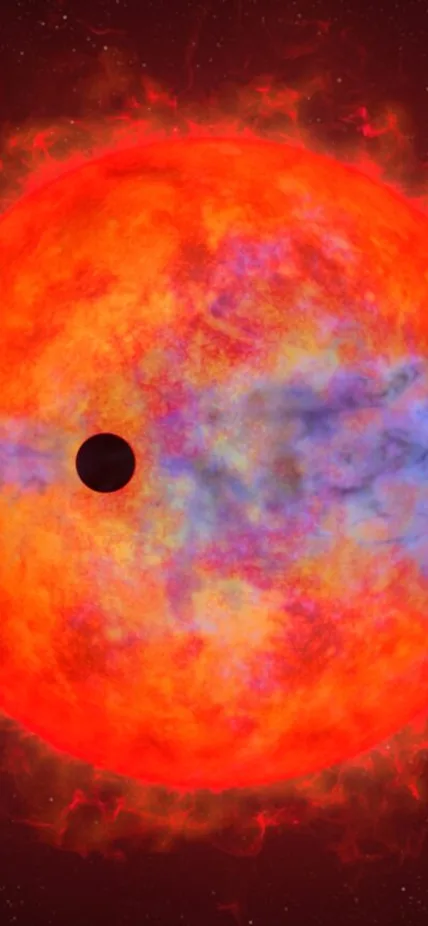

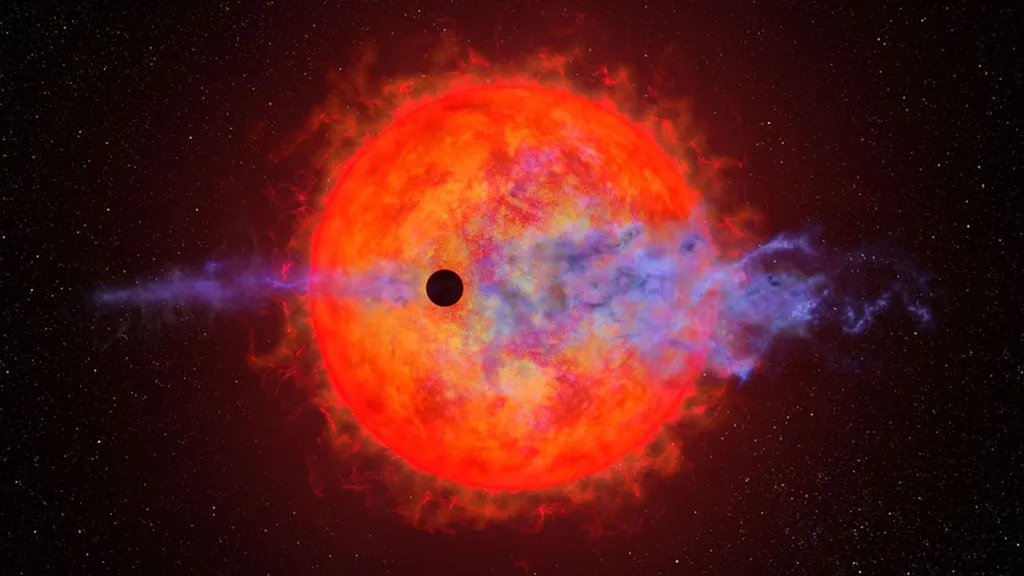

This artist's illustration shows a planet (dark silhouette) passing in front of the red dwarf star AU Microscopii. The planet is so close to the eruptive star a ferocious blast of stellar wind and blistering ultraviolet radiation is heating the planet's hydrogen atmosphere, causing it to escape into space. This process may eventually leave behind a rocky core. This process may eventually leave behind a rocky core. Credit: NASA, ESA, and Joseph Olmsted (STScI)

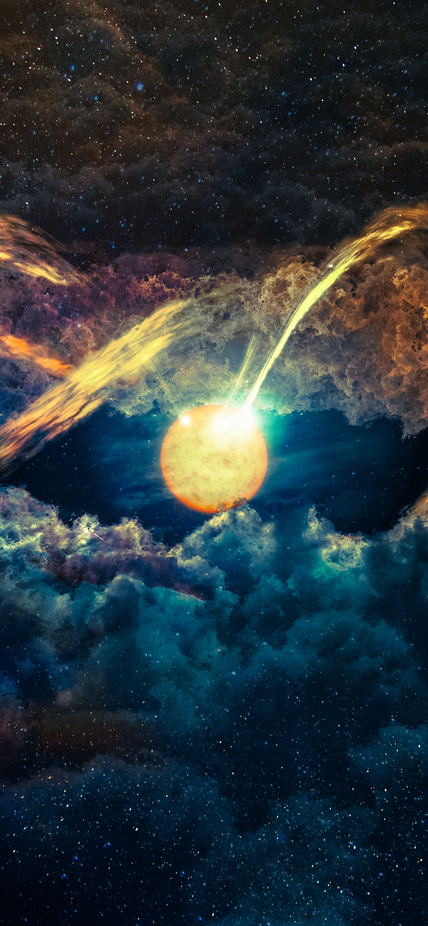

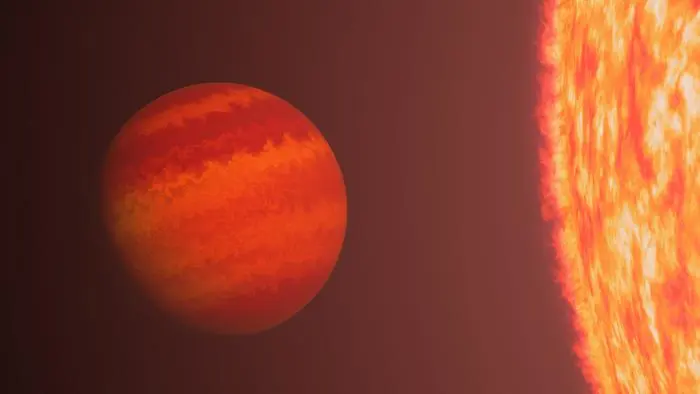

Artist’s concept of TIC365102760 b, nicknamed Phoenix for its ability to survive a red giant star’s intense radiation from up close. Credit: Roberto Molar Candanosa/Johns Hopkins University

Q: So, it sounds like a lot of the planets that you're talking about here are not ones where we would look for life, since they’re being irradiated or their atmospheres have been stripped away, or something else weird has happened to them. Can we still learn about habitability from them?

Vissapragada: Yes, yes, certainly. One aspect is we think atmospheres are very important for the presence of life. In the context of habitability, if a rocky planet isn't able to hold on to its atmosphere for some reason, then that's something that we really want to understand. It’s critical to know which planets are able, by the laws of planetary evolution, to hold on to their atmospheres and which ones aren't.

I think habitability is an angle that is always interesting, although sometimes in the background, because, of course, I think the objects that I’m studying presently are very interesting in their own right, too. But it's always part of the backdrop of my thinking. For example, the processes I’m focusing on helped shape the evolution of our own inner Solar System. Venus and even Earth experienced some atmospheric escape. So even though the planets that are the focus of my work are not anyplace someone would want to live, they are still interesting for thinking about how habitability evolves.

Q: And so, what can these more extreme cases of planetary evolution teach us about the range of experiences that a planet could have over the course of its existence?

Vissapragada: Well, for example, these Neptune-sized planets that are possibly undergoing or have undergone extreme mass loss can teach us about what the insides of other planets look like. Historically, one of the most challenging things to learn about a planet is its interior, including the pressure regimes, temperature regimes, chemistry regimes, mineralogy regimes, and more.

On Earth, seismological tools can teach us things about our planet’s interior, as can rocks and minerals that come up from the depths. And within our Solar System we can learn some things about Saturn from ring seismology, which uses the planet’s rings as a seismometer, and we can learn some things about Jupiter’s interior by the way it perturbs the orbits of spacecraft like Juno.

But, in general, it’s very difficult to learn about planetary interiors. And in the case of these rare exoplanets, nature has possibly done the work for us by literally removing the atmosphere of a gas giant and exposing what its core looks like. I think that it is such a rich environment for learning about a part of planetary science that is typically very challenging to probe observationally.

Q: So, these types of high-drama planets, I’m thinking of them as Real Housewives planets, they have crazy life stories. What are some other examples of information that we can glean from them about how planets work?

Vissapragada: There are just so many mysteries around this class of planets right now. And they are challenging, because they are so rare. But the edges of the exoplanet population are really interesting to me, in part, because they enable us to study some aspects of planetary evolution on human timescales. We can actually watch planets lose their atmospheres. And we can watch planets with orbits that are shrinking. We can observe some of these processes on a 10-year timescale when so much of astronomy is happening on a 10-million-year timescale or a 10-billion-year timescale.

Vissapragada's work involves several space- and ground-based telescopes, including JWST.

Vissapragada has also used the Hubble Space Telescope for his research on atmospheric escape. Credit: NASA

Vissapragada's research also involves the Magellan telescopes at Carnegie's Las Campanas Observatory in Chile. He uses the Planet Finder Spectrograph instrument, which was developed by Observatories and Earth and Planets Laboratory scientists.

Q: Do we have a sense of whether these planets are rare because we haven’t found more of them yet, or do just not many of them ever come into being?

Vissapragada: I think we do have an answer, and it's mostly the latter. It's mostly because they're intrinsically rare objects. And the reason we know the answer is because most of these planets are being found very close to their host stars, and for certain planet-finding techniques like the transit method or radial velocity, it's inherently easier to find objects with close-in orbits. This means we know, more or less, how good these techniques are at discovering these kinds of exoplanets and that we can be confident that we aren’t missing hundreds of them out there. This question does make me think about how many other kinds of weird, dramatic exoplanet living situations we are yet to discover though, because they exist past the threshold of current detectability.

Q: What kinds of technological innovations or developments are going to bring about the next big breakthroughs in exoplanet knowledge?

Vissapragada: I think the Nancy Grace Roman telescope and the next release of data from the Gaia mission are going to be huge, unlocking information about the demographics of planets at a totally different scale. There are going to be thousands of new planets discovered via a completely different technique than the ones that many of us were trained to use and have used throughout our careers so far. It will be time to take out the textbooks and relearn things and to develop strategies for thinking our ways around new problems that are revealed by this influx of information. That’s one of the things I really like about this job. It’s a field that moves really fast and requires you to be on your toes.

Q: OK so last question, and perhaps it’s a bit silly. But do you have a dream object or a dream phenomenon that you would love to observe?

Vissapragada: I have a list in a notetaking app of all the things that I would like to try to figure out a way to probe observationally for the first time. And there’s a reason this list is long, because there are a lot of things out there that if they were easy to search for, we would have found them already. So, I’m always thinking about how to approach things that are inherently difficult to do. One is the idea of revealing auroral processes on other planets, like the aurora borealis and aurora australis on Earth. And, yes, in general magnetic fields are a very interesting topic to think about how to study on other worlds. I wish that there were better ways to probe the bulk hydrogen content of other planets. It’s the most common constituent of planetary atmospheres but it’s spectroscopically very challenging to see and so we have to think about clever ways to get at that question.

Q: It seems like everything you’ve laid out here, from these big questions to these short timescales creates an environment that really breeds ideation.

Vissapragada: The creativity is definitely my favorite aspect of this field.