In the lab and in the field—as well as through detailed mathematical simulations— Carnegie Biosphere Sciences & Engineering (BSE) researchers explore the interconnected web of life on Earth. Their expertise ranges from native North American grasslands to fragile marine environments. It even includes inhospitable hot springs that may mimic the conditions in which life first evolved.

“Strong collaborations across our areas of expertise promise to provide new dimensions to our understanding of not only life on Earth, but also life’s position in the universe,” said Interim BSE Director Yixian Zheng.

Corals are marine invertebrates that build large exoskeletons from which reefs are constructed. But this architecture is only possible because of a mutually beneficial relationship between the coral and various species of single-celled algae called dinoflagellates that live inside individual coral cells. For years, biologists tried to determine the mechanism by which the coral host is able to recognize the algal species with which is compatible—as well as to reject other, less-desirable species—and then to ingest and maintain them in a symbiotic arrangement. A research team led by Interim Biosphere Sciences & Engineering Director Yixian Zheng revealed the the type of cell that enables a soft coral to recognize and take up the photosynthetic algae with which it maintains a symbiotic relationship, as well as the genes responsible for this transaction. Ed Hirschmugl/Carnegie Science

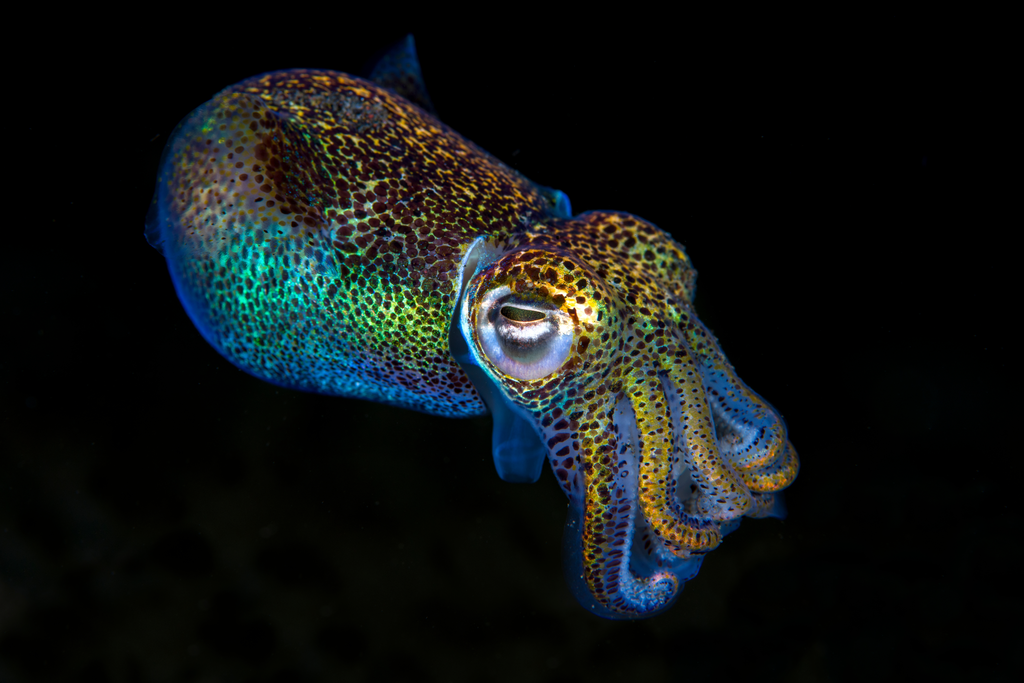

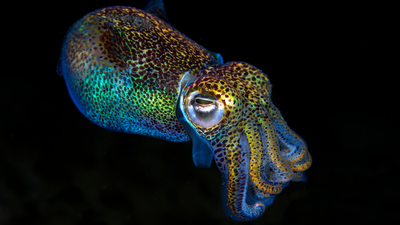

Carnegie's Margaret McFall-Ngai is a recognized thought leader regarding the cornerstone role microbiology plays in the life sciences. Her research specializes in beneficial relationships between animals and bacteria, including the establishment and maintenance of symbiosis, the evolution of these interactions, and how they affect the animal’s health. Much of her work has concerned the relationship between the bobtail squid and the luminescent bacterium Vibrio fischeri, which colonizes the nocturnal cephalopod and allows it to camouflage itself by Moon- and starlight to hunt and escape predators. Using this association as a model, she has been able to elucidate many details about how the microbiome shapes various aspects of animal life, including development and longevity. Credit: Shutterstock

Carnegie's Emily Zakem is trying to connect marine microbial activity to the large-scale biogeochemistry, and then ultimately link it to the climate system. Her work aims to bridge the micro scale with a global scale, which could potentially inform how we model the Earth system and its carbon cycle and nutrient cycling. Credit: Shutterstock

Xenia growing in Carnegie Science's coral reasearch facility

Berry's bobtail squid, Euprymna berryi, hunting in the night.

Tidepool formation in La Jolla, California

“I’m an astronomer, and one of the things I’ve spent a lot of time and energy on over the last year is gaining a deeper understanding of the work that our biologists are doing,” said Carnegie Science President John Mulchaey, whose tenure started in late November 2024. “One of the coolest aspects of this role has been realizing the opportunities that are arrayed before us for tapping into the research revolution that’s occurring in the life sciences right now.”

This work presents ample opportunities for collaboration between our BSE biologists and our Earth & Planets Laboratory astrobiologists—who are pursuing the answers to similar questions from a different perspective.

Together, they can elucidate ways to look for the distinct chemical fingerprints of biological processes, like photosynthesis, on other planets, as well as how to differentiate between these signals and the chemical output from geological events, like volcanoes, which can also be seen from space.

Find out about three ways that our biologists and astrobiologists are traversing disciplinary boundaries and contributing to our Blueprint for Discovery:

Probing Algae's Superpowers

Algae can grow with amazing speed—as anyone who has ever maintained a swimming pool can tell you. This is thanks to algae’s ability to biochemically boost photosynthesis. One of the crucial steps of the photosynthetic process involves pulling carbon dioxide out of the air and then using it to construct carbon-based sugars inside a cellular factory. But funny enough, plants aren’t actually very efficient at doing this, despite the centrality of photosynthesis to their way of life. It turns out that photosynthesis is a victim of its own success. When it first evolved in bacteria about 3 billion years ago, the planet’s atmosphere had plenty of carbon dioxide. Now, however, our atmosphere is oxygen rich thanks to photosynthetic activity. And oxygen slows the gears of the photosynthetic apparatus. Algae, however, have mechanisms for concentrating carbon dioxide in the cell, speeding up their production of sugars and other nutrients. Carnegie’s Adrien Burlacot has spent much of his career elucidating these capabilities in detail, with a particular focus on the bio-energetic mechanisms that make them possible. Harnessing algae’s special abilities could increase agricultural productivity, fight global hunger, and remove more carbon pollution from the atmosphere—contributing to climate change mitigation.

Exploring Extremophiles

‘Omics’ is a relatively new research term that refers to a collective effort to identify, characterize, and quantify groups of biomolecules within a cell—or in a community—and to understand their contributions to the complex physiology of the organism—or to dynamic group interactions. It represents the intersection of a variety of specialties, including genomics, proteomics, metabolomics. In many ways, it leapfrogs over the classical methods of microbiology and takes a systems view of studying biology. Carnegie’s Devaki Bhaya is pursuing an ‘omics approach to understanding the microbial communities that are adapted to thrive in the extreme conditions of Yellowstone National Park’s hot springs. Her research has revealed the lateral transfer of genes between microbes, which is the bacterial version of loaning your neighbor a cup of sugar. Looking ahead, she is keen to link her work on extremophiles with the origins of life research undertaken by astrobiologists and geomicrobiologists.

Evidence of Ancient Photosynthesis

Earth is an active planet, which means that it’s difficult to trace chemical signals backward through time, particularly evidence of biochemical interactions. These molecules are irrevocably altered by geologic processes. As a result, paleobiologists who search for signs of Earth’s most ancient life have long relied on fossil organisms, including microscopic fossils of single cells, as well as the mineralized remains of cellular structures such as mound-like stromatolites, which provide convincing evidence of life as far back as 3.5 billion years ago. However, such remains are few and far between. Pairing cutting-edge chemistry with artificial intelligence, a multidisciplinary team of scientists led by Carnegie Earth & Planets Laboratory scientists Robert Hazen, Michael Wong, and Anirudh Prabhu recently found molecular evidence that oxygen-producing photosynthesis was at work at least 2.5 billion years ago. This finding extends the chemical record of photosynthesis preserved in carbon molecules by over 800 million years. The researchers concluded that information-rich attributes of ancient organic matter, even though highly degraded and with few if any surviving biomolecules, can still reveal much about the nature and evolution of life.