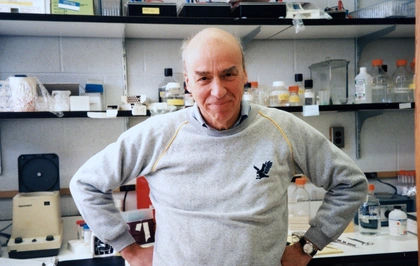

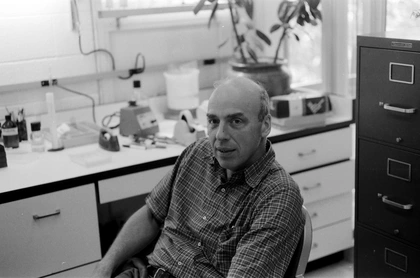

Washington, DC—Carnegie Science developmental biologist Donald Brown, whose pioneering molecular biology research advanced our understanding of the fundamental nature of genes and led to early breakthroughs in genetic engineering, died the night of May 31. He was 91.

Brown served as the director of Carnegie’s former Department of Embryology from 1976 through 1994. He is widely recognized for his role in spearheading and championing the ability to manipulate genes in a laboratory environment.

Brown played a leading role in transforming biology from a primarily observational pursuit, in which researchers relied on microscopic observations of processes, to a mechanistic discipline in which investigators used novel techniques to study the interlocking functions of genes coding and cellular components.

“Don was an exceptional scientist and a thoughtful mentor to generations of biologists,” said Eric D. Isaacs, President of Carnegie Science. “His work embodied the unlimited intellectual curiosity and boldness that Carnegie Science was created to foster and support. Don Brown’s work transformed humanity’s understanding of molecular biology, and every day his research informs new discoveries about the nature of life.”

Brown, who earned his M.D. and master’s degree in biochemistry from the University of Chicago in 1956, first became interested in the molecular underpinnings of embryonic development when he was in medical school.

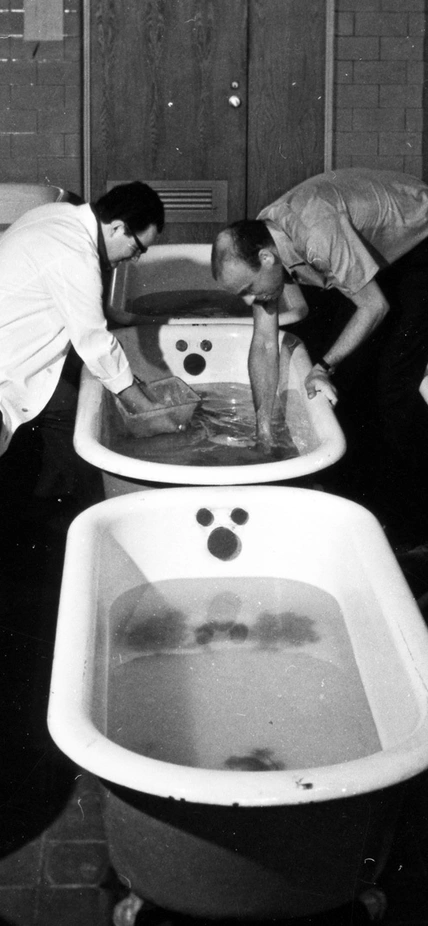

After joining Carnegie as a fellow in 1961, Brown began interrogating the protein-synthesis process that forms the basis of nearly every cellular process. With his collaborator, John Gurdon of the University of Cambridge, Brown discerned that a dense, spherical structure found inside the nucleus, called the nucleolus, manufactures the structural rRNAs of the ribosome, the protein factory within the cell. Moreover, they showed that genes encoding rRNA could be purified and studied in the laboratory.

“This discovery spurred an explosion of interest in studying animal genes as DNA molecules whose properties and interactions can be characterized biochemically. Within a short time, further advances allowed Don’s approach to be applied to all genes, launching a revolution in our understanding of animal development from a fertilized egg into a fully functioning organism,” said longtime Carnegie colleague Allan Spradling.

In 2012, Brown and Columbia University’s Tom Maniatis were jointly honored by the Lasker Foundation with a Lasker-Koshland Special Achievement Award in Medical Science, given for “exceptional leadership and citizenship in biomedical science—exemplified by fundamental discoveries concerning the nature of genes; by selfless commitment to young scientists; and by disseminating revolutionary technologies to the scientific community.”

Brown was renowned for his mentorship of young researchers, both at Carnegie and as the founder of the Life Sciences Research Foundation, which supports early career scientists during their postdoctoral work.

In learning of Brown’s death, Nina Federoff, a National Medal of Science laureate who worked with him at Carnegie from 1978 to 1995, praised his commitment to focusing on doing good science, not publishing for the sake of it. “I treasured Don Brown's belief that life is too short to make two papers out of one,” she said.

During a January 2022 celebration of Brown’s life and work, many of his former mentees and collaborators, including Fedoroff, spoke about his impact on their professional lives.

“Don is the key person in my life who made my own career,” said Tasuku Honjo, who was honored with the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2018. He credited Brown with encouraging him to pursue molecular immunology, as well as facilitating an important meeting with a leading scientist from the National Institutes of Health.

Added Steven McKnight, a biochemistry professor at University of Texas Southwestern who worked with Brown for 14 years, “he just had distinctive leadership skills that gave all of us as young scientists confidence that we could climb the mountain.”

Brown was a member of the National Academy of Sciences, the American Philosophical Society, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Among his many professional recognitions, he received the Louisa Gross Horwitz Award from Columbia University, the E.B. Wilson Award from the American Society of Cell Biology, and a lifetime achievement award from the Society for Developmental Biology.

Brown is survived by his wife of 65 years, Linda Weil Brown; children Deborah, Christopher, and Sharon; sister-in-law Marian; grandchildren Emily, Don, Jennifer, Lauren, Spencer, and Alicia; and great-grandchildren Braiden, Jackson, Tanner, Brooks, and Vivien.