Breakthrough for Understanding the Coral Algae Partnership

Carnegie In The News

"As waters continue warming, such bleaching events will likely become more common, Romanó de Orte said, which means more dead reefs dominated by turf algae. ‘This has been happening a lot,’ she said. ‘We’re trying to figure out what reefs will look like in the future."

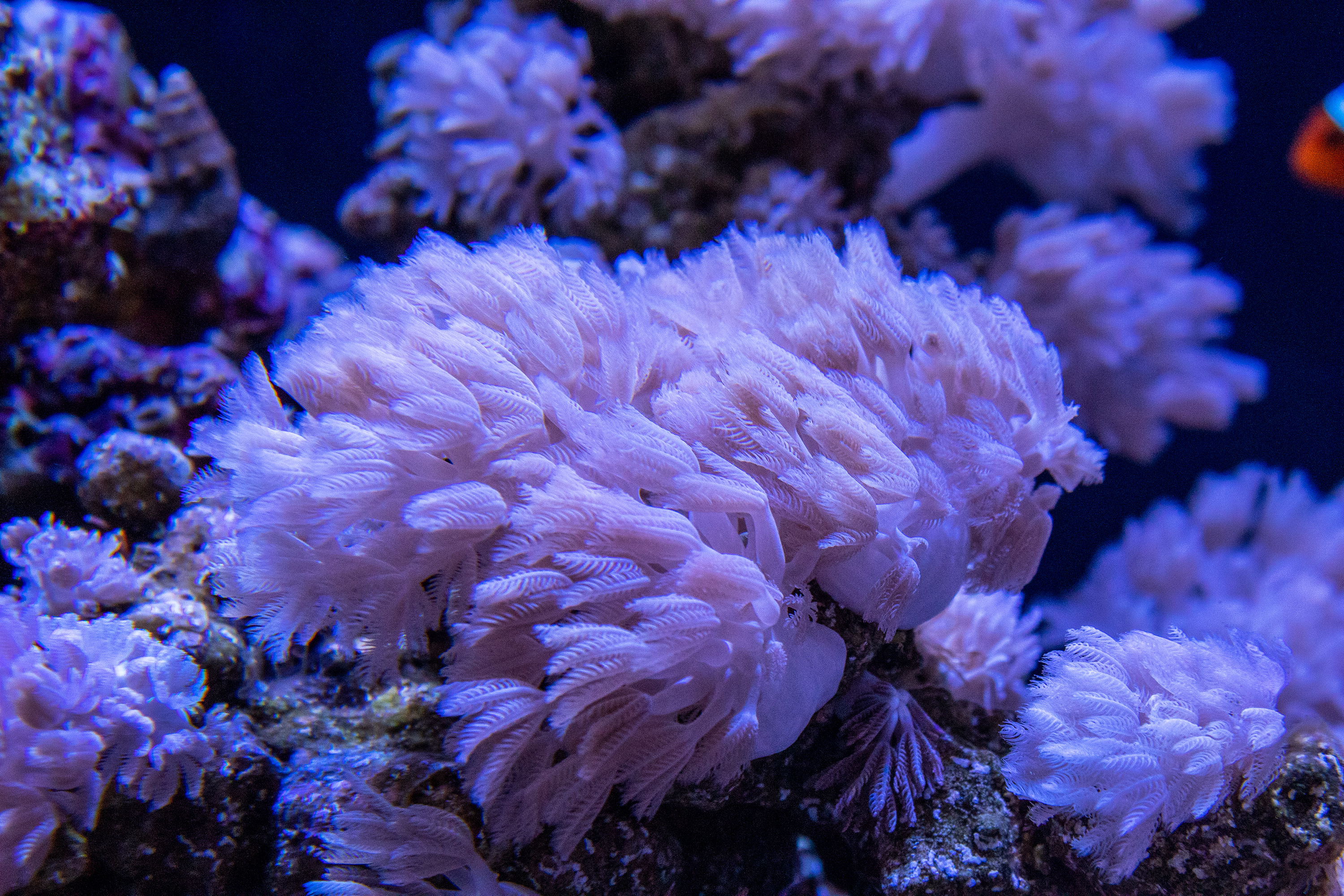

Corals are marine invertebrates that can build large exoskeletons, which construct ecologically important reefs.

Corals depend on algae for food, while algae obtain compounds from corals that they then use in photosynthesis to convert sunlight into that food, including sugars and amino acids. This symbiotic partnership is crucial for the health of both. However, corals cannot tolerate rising ocean temperatures because it causes coral bleaching (expulsion of algae) and death. Carnegie researchers Minjie Hu, Xiaobin Zheng, Chen-Ming Fan, and Yixian Zheng recently identified the cell that enables the soft coral Xenia to recognize and live with the symbiotic alga, plus the responsible genes, solving a long-standing biological mystery, which could boost coral conservation.

The team used the lavender, fast-growing, soft coral Xenia to investigate the cell types and molecular chain of events that control coral-algae symbiosis.

Corals depend on various species of single-celled algae called dinoflagellates that live inside individual coral cells. For years, researchers have been trying to determine the mechanisms by which the coral host recognizes a compatible algal species, rejects other species, and then ingests and maintains the algae in their symbiotic partnership.

Earlier this year, Yixian Zheng was competitively selected as one of 15 scientists awarded a grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation to support research on symbiosis in aquatic systems under its new Symbiosis in Aquatic Systems Initiative.

Yixian Zheng poses with the coral research team. From left to right: Xiaobin Zheng, John Sittmann (who recently joined the coral team), Minjie Hu, Yixian Zheng, Chen-Ming Fan. Image courtesy Navid Marvi, Carnegie Institution for Science

The team used the fast-growing, soft coral Xenia to investigate the cell types and molecular chain reactions that orchestrate the symbiosis. They used a wide range of advanced genomic and bioinformatic tools and demonstrated the power of these tools in studying coral biology. The researchers identified the cell type required and discovered that it expresses a distinct set of genes, which enable it to identify, ingest, and maintain the alga in a specialized compartment, which also protects the alga from being attacked by the coral’s immune system. The researchers showed that the uptake process occurs over five stages. Stage one is a presymbiotic stage. Stage two involves algae uptake, while stage three consists of mature, algae-hosting cells. Coral cells then start to lose algae in the fourth stage to finally become stage five, algae-free cells. The team plans to further understand how each stage reacts to different environmental stressors, including the functioning genes, and which stage is most important for corals to recover from a bleaching event.