Do you know what the Sun sounds like? To astrophysicist Conny Aerts, listening to stars is like hearing “a symphony from the cosmos.”

Aerts, an astronomy professor at KU Leuven in Belgium, shared her research on the seismic waves that ripple through stars with a rapt crowd at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library in downtown Washington, D.C., last week.

“For me, stars are just three-dimensional musical instruments,” Aerts explained in conversation with Emmy winning journalist Frank Sesno, the Director of Strategic Initiatives at George Washington University.

A pioneer in the field of asteroseismology, or as she calls them “starquakes,” Aerts was recognized last year with the prestigious Kavli Prize in Astrophysics. The October 25 Carnegie program was presented jointly with The Kavli Foundation, the Royal Embassy of Norway, and the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters.

Caused by a variety of physical phenomena—including the gravity of nearby celestial bodies and the activity of a star’s outer, gaseous layers—hundreds of these starquakes could be moving through a star at any given moment.

Just as geoscientists use seismic waves traveling through the Earth as a kind of “ultrasound” to reveal structures in our planet’s interior, Aerts and her asteroseismology colleagues use these stellar ripples to reveal critical information about stars, including their age, size, and weight.

“Starquakes and the waves that they create, they inform us about the internal structure of the star,” Aerts told Sesno. “What is that? It’s the density mainly, the temperature also, above all, also how the gas is rotating around.”

For many years, asteroseismology was primarily the domain of theoretical astrophysics. Satellite missions opened the door to a deeper understanding of the field.

“We had developed theories,” Aerts explained. “We just didn’t have data to couple the observations to the theory and so for that we needed instruments on space missions.”

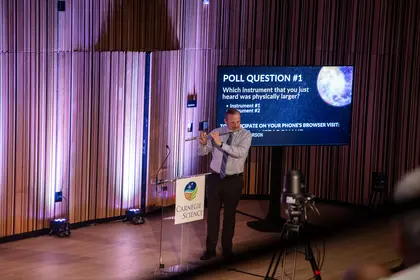

Throughout the evening, Sesno engaged the audience with interactive experiences—including a live musical demonstration illustrating the sonic differences between a flute and a tiny piccolo, as well as recordings of our Sun, a low-mass helium star, and a red giant, which Aerts joked sounded like it would be popular at a Belgian disco.

Attendees also used their phones to participate in online polls about stellar fun facts and to weigh in on the kind of star they’d most like to orbit if they lived on another planet.

“Stars get born in interstellar star-forming nebula and then, depending on the amount of material they get at birth, they can either can live a quiet life like our Sun—luckily for us it’s a very quiet, a little boring star, one could say,” Aerts joked with Sesno. “But you also have stars that are born with way more gas … they lead a violent life; a very fast life and they will explode.”

These big, short-lived stars make most of the matter in the universe, Aerts explained, calling them the “steel factories” of the cosmos. So, counting, sizing, and age-dating them helps researchers like her understand how the chemistry of the universe is evolving and how the raw materials for life are distributed.

“There are billions of galaxies with billions of stars,” Aerts said when asked by Sesno about the possibility of discovering life elsewhere. “Future generations will find it.”

Aerts also discussed her commitment to mentorship—with a special emphasis on encouraging early career women that they “can be a mama and an astrophysicist at the same time”—as well as her sponsorship of a young Ukrainian student who was displaced by the war with Russia.

“I’m doing my job for the stars and for my passion, but also to educate youngsters and make them feel welcome, but also inspired to do teamwork,” Aerts said.

Kavli President Cynthia Friend concurred with the emphasis Aerts places on outreach and education, noting that in addition to her “infectious” passion for sharing her research, “Conny is dedicated to developing the next generation of scientists.”

In concluding the program, Carnegie President Eric D. Isaacs thanked Aerts for her dedication and eagerness to engage the public about astronomy.

“It’s wonderful how committed you are to really important science, but also thank you for your commitment to early career scientists … your commitment to diversity,” he said.