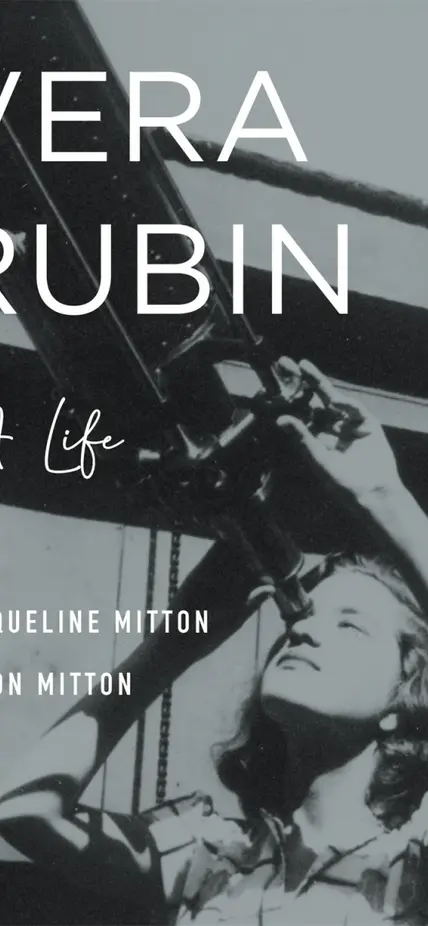

Earlier this year, Carnegie sat down (via Zoom) with Jacqueline and Simon Mitton, authors of Vera Rubin: A Life, the first biography of the legendary Carnegie scientist Vera Rubin, whose work on the rotation curves of galaxies confirmed the existence of dark matter.

____

Q: This is the first biography of Vera and it’s about time. Were you surprised when you started this project to realize that this hasn’t been done before?

Simon: We weren’t surprised at all.

Jacqueline: In terms of why there had not been a biography, I think very frequently it’s a person’s passing on that provokes the thought that “it’s time for a biography,” particularly with a prominent scientist. But there was another really important thing, which just about worked out for us, and that was all of her papers went to the Library of Congress when she finally retired in 2014. It turned out that she really had kept all her files in pristine order and hadn’t thrown anything out. Everything was there going back to before she went to [Department of Terrestrial Magnetism] DTM when she was still at Georgetown. We had the privilege of being the first people to see these documents. We were fairly sure that many of those old letters going back to the 1960s and so on that Vera herself had not looked at for decades.

Q: Your having access to those letters really adds to that feeling when you’re reading the book, it feels so alive. It doesn’t feel like a dry, dusty history. It feels you’re hearing the story from someone who knew her.

Jacqueline: When you’re deep into writing biography you just sort of feel that you are living with this person—they are so alive to you.

Simon: You reach a point where you know so much about them, you can imagine they’re in the same room as you.

Q: From a timing perspective, the book is really interesting because Vera had two significant anniversaries in 2020 for her seminal 1970 and 1980 papers.

Jacqueline: It never occurred to us. What happened was that she passed away at the end of 2016 and a few months later Harvard University Press was thinking, “maybe she would be a good person for a biography” and we heard that. It was just “we’ve got to do this!”

Simon: I have approached writing biography by putting the storyline and the people first and having the scientific achievements in there but not aiming to do what I’m afraid some historians of science do, which is just go through the timeline of the papers they were publishing. I mean, that is just so boring.

Q: It sounds like the scientific anniversaries she just crossed are very much a coincidence.

Jacqueline: A happy coincidence!

Q: Of the many quotes that can be attributed to Vera, a favorite of ours is when she talked about how she chose to work on ideas that were a little bit out of the mainstream so as not to be “pressured by bandwagons.” How much do you think the philosophical approach by which she went about selecting topics to investigate contributed to the tremendous success that she had?

Jacqueline: This is a really profound question, actually. You can’t separate Vera’s professional life from her family life. She was a totality of a person. She said sometimes having a family life made it easier for her to have a professional life rather than necessarily the other way around. They were all tied together. So, everything that happened with the development of Vera’s career was partially around what is realistic for her as a person, particularly when she was setting out. But within that, she also developed, rapidly, a very clear view that what really turned her on was being in the dome observing. Her philosophy was that she liked observing, and she probably recognized that she was rather good at observing. She had what it took. Everything was subsumed in this passion for observing. So, she took the view that she wanted to make observations that were so good and so reliable that other people would accept them, and nobody would doubt them. She saw herself as having a mission to make good observations. She liked the idea of being able to do something where nobody else was going to be able to interfere with her and she wasn’t in competition. She clearly hated the competition. She did love the idea that she would be able to just do what she loved on her own terms.

Simon: Observational astronomy is about finding out about the physics of stars. She was a very, very good fundamental experimental physicist, in that she wanted to measure things to the limits of what the technology would let you do, then to make sure that you were meticulous in reducing the data. Classical physics done at the frontiers of what technology will allow you to do—that was what she was like as an observer.

Q: In addition to her scientific legacy, Vera certainly also has a significant legacy as a champion for women in science.

Simon: In future generations, she will be held up as a sort of an iconic figure for standing up against discrimination.

Jacqueline: [Carnegie Trustee] Sandra Faber made this point in her tribute in Scientific American that Vera Rubin with Margaret Burbidge were twin guiding lines. When Margaret Burbidge made her stand, then Vera was suddenly, everything was unleashed. She spoke herself in some of the things she wrote about—almost the painfulness of going into universities or around as visitors and finding that there were women who never had another female scientist to speak to and bearing their stories and sharing them was almost emotionally painful for her. She somehow had the strength to do that. Somehow or another she pulled all this in alongside her incredible observing schedule. Her stamina is just unbelievable!

Q: What do you hope readers will take away from your book?

Jacqueline: What I hope is that people just enjoy reading the book. That we’ve presented her as the person that she was and also show her as an ongoing role model, even though she’s passed on. To be an inspiration to others, because she encouraged people to be persistent against all the odds. She also had this extraordinary joy in life.

Simon: Throughout the project one of the things I had in the back of my mind was it would be nice if we could produce a book that educators, career advisors, university admissions advisors, and all those sorts of things could direct hesitant or curious 15, 16, 17-year-old women toward if they are wondering “would I be able to succeed in science?”

Interview edited for brevity and clarity.